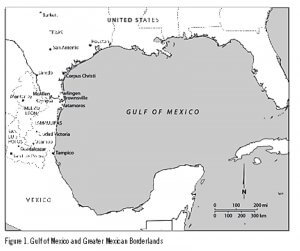

At least five years before Mexican labor activist Caritina Piña arrived in the working-class barrio of Villa Cecilia in the outskirts of Tampico, Reynalda González Parra had co-founded one of the most radical labor collectives in the entire world. It was 1915 and amid one of the bloodiest revolutions of the twentieth century González Parra, alongside Mexican, Spanish, and other activists, founded the Tampico local of the Casa del Obrero Mundial (COM)—the House of the Global Worker.

It became a leading hub of radical labor activity in the Gulf of Mexico region’s faja de oro negro. This oil belt local along the Gulf of Mexico collaborated with numerous labor collectives including the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM). The IWW, founded in 1912, promoted its global union message while the PLM, almost a decade prior, had garnered support from workers and intellectuals to end a multi-year dictatorship in Mexico that favored foreign interests over the well-being of its Mexican citizenry. The COM, often with the support of IWW and PLM branch members, sought to move beyond liberal reforms and national autonomy to reconstruct work and society through worker collectives.

Reynalda González Parra and Caritina Piña figured prominently in the labor movement in the Gulf Coast region during the years of the 1910 Mexican Revolution through the 1930s. González Parra swam with so-called big fish Mexico City COM co-founder Jacinto Huitrón and Ricardo Treviño, while Piña worked closely with anarchists Esteban Méndez Guerra and Librado Rivera.

González Parra’s writings appear alongside editorials and commentaries by Ricardo Flores Magón and Librado Rivera. These men are more well-known labor revolutionaries and have received the bulk of scholarly attention. Despite her loud, public voice in a visionary world of gender, labor, and racial equality, free of national boundaries and religious impositions, González Parra’s voice has remained hidden.

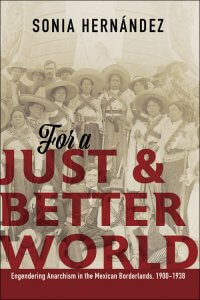

For a Just and Better World: Engendering Anarchism in the Mexican Borderlands, 1900-1938 expands the field by centering the early activism of women such as González Parra and Piña in a growing labor movement that drew inspiration from anarchist ideas. González Parra, co-founder of the Tampico COM laid the groundwork for women such as Caritina Piña, who emerged as strong advocate of political prisoners and workers’ rights in Mexico and beyond during the 1920s and early 1930s. Piña worked closely with the COM as well as anarcho-syndicalist groups reaching out to women, men, and labor organizations in Mexico and across the border in places such as Texas and New York.

Initiating women in the movement

Ideas about worker autonomy and the right to dignidad or a dignified way of life led women to engage in collective struggles. Writings on dignity and autonomy, dating to the French Revolution, circulated across the globe, were translated, and further shared among communities of workers and residents. Such ideas influenced González Parra and Piña to push the boundaries of anarchist thought to make room for women in the broadest sense.

González Parra became introduced to anarchist thought, particularly the ideas of Francisco Ferrer i Guardia, Teresa Claramunt, and Ricardo Flores Magón upon her arrival in Mexico City, most likely after leaving her native Chihuahua before the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution. Her writings in the Tampico anarchist press, while not extensive, circulated within and beyond Mexico’s borders and her labor activism in the port of Tampico and Mexico City are noteworthy. Her feminismo was anchored in the possibilities that an anarchist vía or route offered. González Parra’s writings regarding labor conditions, women’s struggles, and general community matters reflected a transnational outlook. Reconceptualizing her surroundings and her community through the prism of other workers’ issues from far-flung places, she made sense of rapid changes taking place in her native Mexico. Promoting a nation-less vision of worker rights, while advocating for women’s equality, González Parra directly shaped the Mexican and greater labor movement that fueled the 1910 Revolution as well as the larger push for labor rights across into Texas via the founding of PLM branches.

The Tampico COM branch included members from the IWW and the PLM, and other local anarchist-influenced groups. It soon became a leading center for revolutionary thought and propaganda for labor matters shared across the Mexican Republic, in Texas, and throughout the Caribbean and beyond the Gulf of Mexico. González Parra helped sustain these crucial nodes of intellectual exchange through her writings and COM activism.

In 1917, González Parra attended the Second Workers’ Congress organized in Tampico and while she was most likely not the only woman in attendance, it appears she was the lone female delegate out of thirty-four delegates representing labor collectives from across the republic.

She further politicized women’s reproductive capacity by urging them to “emancipate yourselves, because then you will produce free children and you will have contributed to the reconstruction…of a new society…”[2] Her revolutionary motherhood, however, would not serve the interests of the new revolutionary regime. For González Parra, individuals such as General Venustiano Carranza had failed the real revolution. Instead, because this vision served the very ideals for which anarchists had risked their lives—it would bring about a new cadre of revolutionary thinkers that would ultimately transform society not by implementing yet another government to represent the nation-state, but by self-governance in a collective trans-border world void of any class distinction. It was a motherhood that served the interests of the women themselves and their communities, not the state.

González Parra’s feminismo transfronterizo reflected her own concerns about the larger transformations unfolding in her environment and her ideas about how best to effect change. She understood the place of organized labor and particularly the place of the organizations supporting workers in gendered terms. She made sense of the COM as a ‘mother guiding a family,’ but refracted through anticlericalism. She urged colleagues to not “make the COM into the type of family that blindly follows God.” She wrote, “don’t make the Casa del Obrero, [which is] our common and loving mother, into what Catholics do… to the family…they tie it to God.” She continued explaining how belief in God created a false dichotomy that at its’ core, destroyed the very foundation of the family. “God…either loves his children or throws them into that so-called hell,” she wrote. She was not against family in the cooperative-egalitarian sense of the term but in her opinion, the family who blindly followed religious doctrine was doomed and more importantly, it was the structuring of family via religion that helped to breed inequality within the home.

This broadening of anarchist thought paved the road for more women to engage in labor activism via small anarchist collectives affiliated with the larger Confederación General de Trabajadores (CGT), of which, by the closing of the Revolution, newcomers such as Caritina Piña joined. By the early 1920s, Piña, following the legacy of González Parra, formed part of a larger corpus of women engaged in labor rights via the CGT and broadened the use of radical motherhood as a powerful rhetorical tool with which to continue the fight “for a just a better world” for all workers.[3]

Piña operated as a transnational cultural labor broker handling correspondence on behalf of the Comité Internacional Pro-Presos Sociales, a group dedicated to freeing political prisoners and labor activists founded by former Pancho Villa soldier, Esteban Méndez Guerra Piña managed donations, welcomed new groups, petitioned on behalf of imprisoned political thinkers, and re-distributed local newspapers and publications from afar. She petitioned on behalf of imprisoned and condemned activists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Librado Rivera, Ricardo Flores Magón, Méndez Guerra and others during transnational crackdowns on radical activism. Her political labors contributed directly to sustaining the labor movement. Carrying on González Parra’s legacy of revolutionary motherhood in pursuit of worker dignity and labor rights abroad, Piña directly helped sustain a regional labor movement which also contributed to the vibrancy of labor movements elsewhere.

While the fight continues to this day in all corners of the globe, individuals such as González Parra and Piña helped to widen and extend this uneven path. For a Just and Better World takes women’s labor activism in this corner of the world—expressed through collective action across geo-political borders often through the politicization of a radical and anarchist-inspired motherhood rhetoric—as a microcosm of women’s radical labor activism in the anarcho-syndicalist tradition. While by the mid to late 1930s, a Mexican socialist government silenced any radical anti-government opposition often by invoking the memory of the Mexican Revolution, the anarchist tradition of direct-action, supporting political prisoners, and maintaining a strong anti-state critique via the small but powerful press, continued in the following years. That legacy is still felt today.

[1] Reynalda González Parra, “A la Mujer,” Germinal, Periódico Libertario (Tampico), Julio 2, 1917, AHLR-HR.

[2] Ibid.

[3] To Grupo Libertario Sacco y Vanzetti from Caritina Piña, Secretaria de Correspondencia, July 6, 1929, AHEMG, IIH-UAT.