On November 21, 1927, twenty Colorado strike policemen shot into a crowd of 500 men, women, and children in the company town of Serene built around the Columbine coalmine, killing six striking coalminers and wounding dozens of protestors (the exact number is disputed to this day). Within days, this violence became known as the Columbine Massacre. It was the turning point of the 1927-1928 statewide coal strike led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

Today, the Columbine Massacre site is buried, literally, under a landfill. The landscaped western slope of this trash mountain functions as open space for a housing subdivision in Erie, Colorado, thirty miles north of Denver and ten miles east of Boulder, built around a golf course where most residents probably know little about the origins of their community park or street names. Even historians know little about the strike, the massacre, or its significance in shaping United States labor policies, especially when contrasted with the far more historically documented—and memorialized–Colorado coal mining tragedy, the 1914 Ludlow Massacre. I explore this historical discrepancy in my 2023 book, Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike.

Some of the elements that drew me to research the Columbine strike include its relative obscurity, the role of the IWW, and Josephine Roche, a Progressive who also happened to be the mining company’s largest stockholder. After teaching the United States survey course for decades, I knew textbooks claimed the IWW died in the 1920s as a consequence of its intense World War I era government persecution. Yet since that union led what one historian accurately calls the most successful strike in Colorado history, perhaps rumors of the IWW’s death had been greatly exaggerated. Josephine Roche was the majority stockholder of the RMFC, Colorado’s third largest coalmining company, which built the town of Serene and the Columbine mine. A college classmate and close friend of Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, she might be the only female coal operator in the United States, and she also served alongside Perkins in FDR’s New Deal cabinet. From the mid-1940s until 1969, Roche was also the right-hand-woman to John L. Lewis, United Mine Workers (UMW) president from 1920-1960. That personal and professional relationship began at the Columbine mine after negative public reactions to the massacre prompted Roche, a classic “maternalist” reformer, to seek a progressive solution to the company’s labor woes. She initiated a contract with the UMW, even though the union had played no role in the strike other than denouncing it. That 1928 contract rescued Lewis in his darkest hour, because the UMW 1927-1928 Central Competitive Field coal strike he had led ended in a crushing defeat. Furthermore, the contract she helped secure played an outsized role in influencing New Deal labor policies and the future of labor history.

An even earlier UMW defeat helped lead to Lewis’s ascendancy within the coalminers’ union. In 1910, the company that would soon be renamed the RMFC—John Roche co-owned it and his daughter Josephine inherited his shares in 1927—did not renew its UMW contract. That initiated what Colorado coalminers called the Long Strike in the state’s northern coalfields, which RMFC dominated. In 1913, the UMW expanded the strike into the state’s southern fields, dominated by John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I). When those coalminers joined the strike, officials evicted them and their families from company housing; many moved into nearby UMW tent colonies. This 1913-1914 phase of the strike, perhaps the deadliest in national history, reached its nadir on April 20, 1914, when a ragtag collection of mine guards, cowboys, and National Guardsmen willing to work without pay set the Ludlow tent colony on fire. The next day, the asphyxiated bodies of two mothers and twelve children were found in a basement dug beneath a tent. Locally and nationally, muckraking and labor publications decried the deaths of these innocents as the Ludlow Massacre. In spite of the publicity, however, the UMW lost the strike and essentially disappeared from the state.

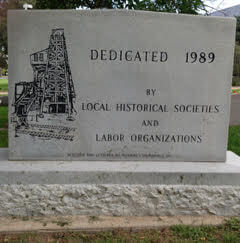

Within this context, the hurried construction and dedication of the Ludlow Monument in 1918 was directly tied to Lewis’s meteoric, undemocratic rise within the UMW and to his masterful reinterpretation of the Ludlow Massacre’s meaning. The 1918 dedication was held not on April 20 but on Memorial Day. Lewis and a roster of UMW leaders officiated the ceremony, while three of the strike’s most important leaders—John Lawson, Ed Doyle, and Mother Jones—were absent. Mother Jones probably wasn’t invited, as her disdain for Lewis and all he stood for made her a pariah among UMW officials. Lawson and Doyle had recently been blackballed from the UMW, two of the first in a long string of potential rivals expelled in a decade’s-long process that consolidated Lewis’s control over the UMW in the 1920s. (In 1928, one of Roche’s most brilliant actions was to hire the former Ludlow hero, John Lawson, as her vice president.) During the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike, the Ludlow monument served as a meeting site for IWW mass rallies, but it also symbolized failed UMW policies. Today, the UMW still plays a central role in Ludlow’s memorialization efforts, and that research community does not dig into these contested origins. Clearly, that limits their findings and their memory.

From 1927 through the early 1930s, Lewis, Roche, remnants of the IWW, and others evoked memories of Ludlow, to mask their own actions that contributed to the Columbine Massacre. By the early 1940s, some historians began arguing that Ludlow’s sacrifices led directly to New Deal labor policies, an argument that erases almost twenty years of labor history. Surely more temporally immediate worker unrest from the 1920s and 1930s, including the IWW-led 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike, scared politicians into enacting 1930s labor laws. These are just some of the messy realities that help explain why the Ludlow Monument still stands and the site of the Columbine Massacre remains buried under a trash dump.