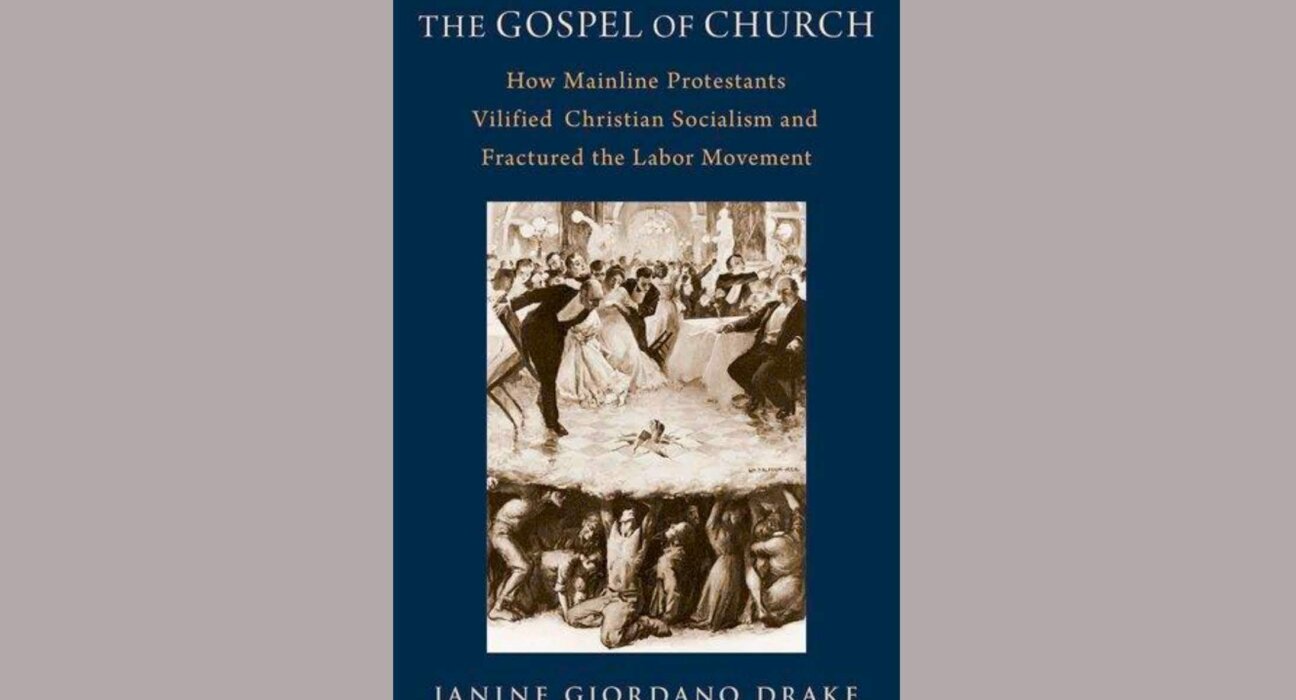

The Gospel of Church: How Mainline Protestants Vilified Christian Socialism and Fractured the Labor Movement, just published by Janine Giordano Drake (Oxford University Press, 2023), chronicles the battles between Christian Socialists and Protestant denominational leaders in the struggle to define the meaning of Christian nationhood. On one hand, a rising movement of Christian Socialists wanted to construct a “Christian nation” as a cooperative commonwealth characterized by the collective ownership of utilities and universal suffrage. On the other hand, Protestant denominational leaders wanted to “Americanize” European immigrants and other people of color but did not think that unions deserved independent cultural and moral authority. The book shows Protestant Social Gospel leaders to be forerunners of the Religious Right: Protestant pastors who took money from big business to advocate for brute capitalism to be transformed into welfare capitalism. The Christian reformers the book highlights were moderates, people who ultimately supported welfare capitalism over collective bargaining rights.

Your book begins with a study of church participation rates in the Gilded Age. Why is this important to working-class history?

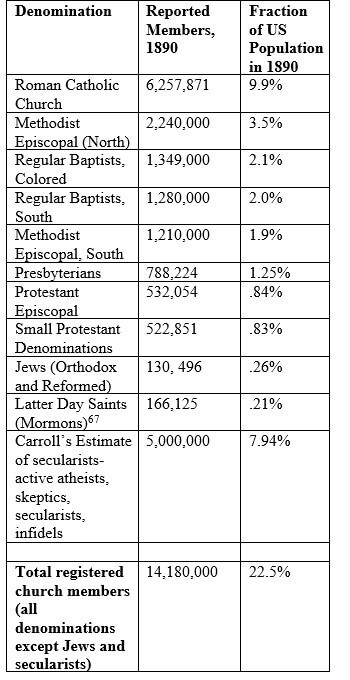

In the late nineteenth century, about 78% of Americans—wage earners, mostly—did not make a habit of regular attendance at a house of worship.

Some of these folks were children and grandchildren of the Second Great Awakening, people who believed in a radical Jesus who were peeved that so few denominational ministers were willing to take political risks for the sake of substantial social reform.

Some of these folks were migrants from Europe, the South, or Mexico, working people who found themselves culturally displaced within factory and mining towns or along the railroad. Among these, many carried on a range of faith traditions, but not within conventional houses of worship. Neither Catholics nor Protestants had the church edifices in the West to meet the needs of all who might have been interested in regular attendance.

Others were skeptics, atheists, and secularists, refugees of endless European battles between Catholics and Protestants, victims of violent Antisemitism, and angry at the whole concept of institutionalized religion. Among these, many believed that the authority of “Science” would soon triumph over Christianity. Friedrich Engels himself suggested that while Christianity was well-suited for a feudal era, but it probably would not survive the advent of democracy.

Not-going-to-church was not a social movement on its own, but it did constitute a significant cultural rebellion against the authority of clergy in North America. I use this first chapter to set up my story of the rise of Christian Socialists.

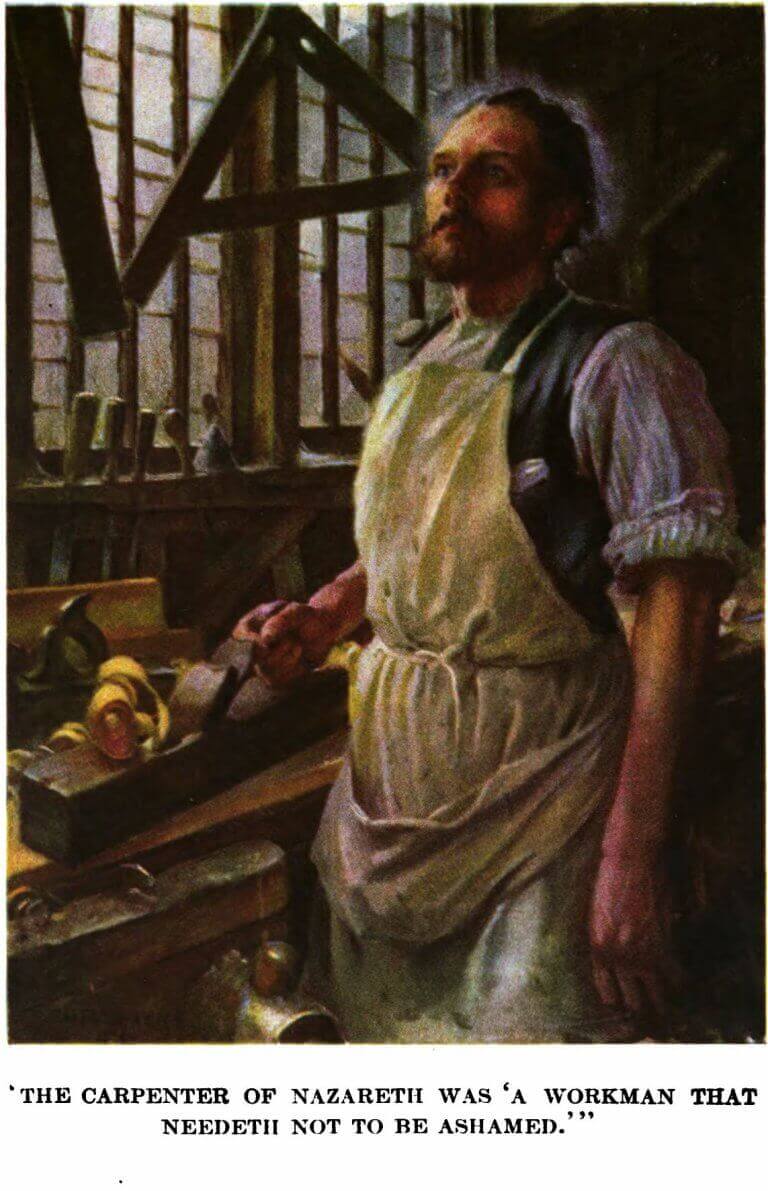

Jesus depicted as a worker, “the Carpenter of Nazareth,” 1912. Credit: Rosemary Feurer collection.

Jesus depicted as a worker, “the Carpenter of Nazareth,” 1912. Credit: Rosemary Feurer collection.Who were Christian Socialists?

Christian Socialists were a massive grassroots movement of Christians who were upset with conventional churches for not acting more decisively to reform and replace the capitalist system. They read books and discussed books like Charles Sheldon’s In His Steps and Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward. Some congregated in institutions called “labor temples” and “people’s churches,” while others loved the Beatitudes, and Jesus the Jewish radical, but detested the institutional church. This eclectic group of rebels were held together by belief in what they called a “Cooperative Commonwealth,” a nation characterized by the cooperative ownership of public utilities and the hope of building more “democratic institutions” through universal suffrage and reforms to the electoral system.

Obviously not all members of the Socialist Party were Christian Socialists. When Debs preached “tolerance,” he was often asking atheists and Christians to please agree to get over their differences and work together. Morris Hillquit, to his credit, agreed with this policy. However, many rank-and-file party members had good reasons to despise what they called “organized religion.” Many had personally fled from religious violence—Catholic and Protestant infighting throughout Europe, pogroms on Jews throughout Russia, and inhumane exploitation of colonized and indigenous peoples identified as “pagans.” Christian Socialists insisted that they were not interested in building up a better church but interested in using Christian principles to build a social safety net at the most local level.

During his long tenure as head of the party, Eugene Debs made many efforts to invite Christian Socialists to make their spiritual home under the socialist big tent. Debs invited the Christian Socialist Fellowship, a secret network of socialist-leaning clergy members, to relocate their headquarters to the same building as the Socialist Party. Before long, Christian Socialists, especially in the rural South, comprised a significant fraction of dues-paying membesr to his party. Debs routinely hired theologically-trained activists, often former ministers, to work as party organizers. By the mid 1910s, there were hundreds of socialist newspapers in the United States which celebrated the hope of a Christian, Cooperative Commonwealth. There were so many, in fact, that the national party started getting requests to name their struggle against conventional churches in the official party platform.

So then what happened to these people?

Well, this is what the book is about! If the first four chapters demonstrate the rise of Christian Socialism at the foundation of the Socialist Party of America, the next five chapters tell the story of how white Protestant ministers united to defeat Christian Socialists.

I suppose I will summarize: In 1908, almost all white Protestant denominations in the United States unite together into a single unit, the Federal Council of Churches, for the primary goal of defeating socialism. They immediately organize the Men and Religion Forward Movement, a national evangelistic campaign to collect data on working people, encourage them to go to church, and remind them that socialism was antithetical to true Christianity. The Federal Council of Churches also authored a pamphlet, the Social Creed, which enumerated the many industrial reforms they were willing to support (higher wages, safer working conditions, shorter workdays, a weekly day of rest, and the end to child labor). Importantly, they are not willing to support the most important demands of the labor movement, like collective bargaining or the freedom of speech. Rather, these ministers want to be known as “neutral” and they want to be called in to “arbitrate” industrial disputes. I argue that the Federal Council of Churches worked very hard to suppress the possibility of labor unions, especially in concert with Christian Socialist ministers, displacing the major denominations from American life.

Why do you end with the 1919 Steel Strike?

As many of us know, the 1919 Great Steel Strike was a tremendous undertaking. Steel workers walked out across several different states in an effort to make union recognition a permanent fixture within modern industries. Elbert Gary at US Steel, on the other hand, was intent on a “return to normalcy” without unions.

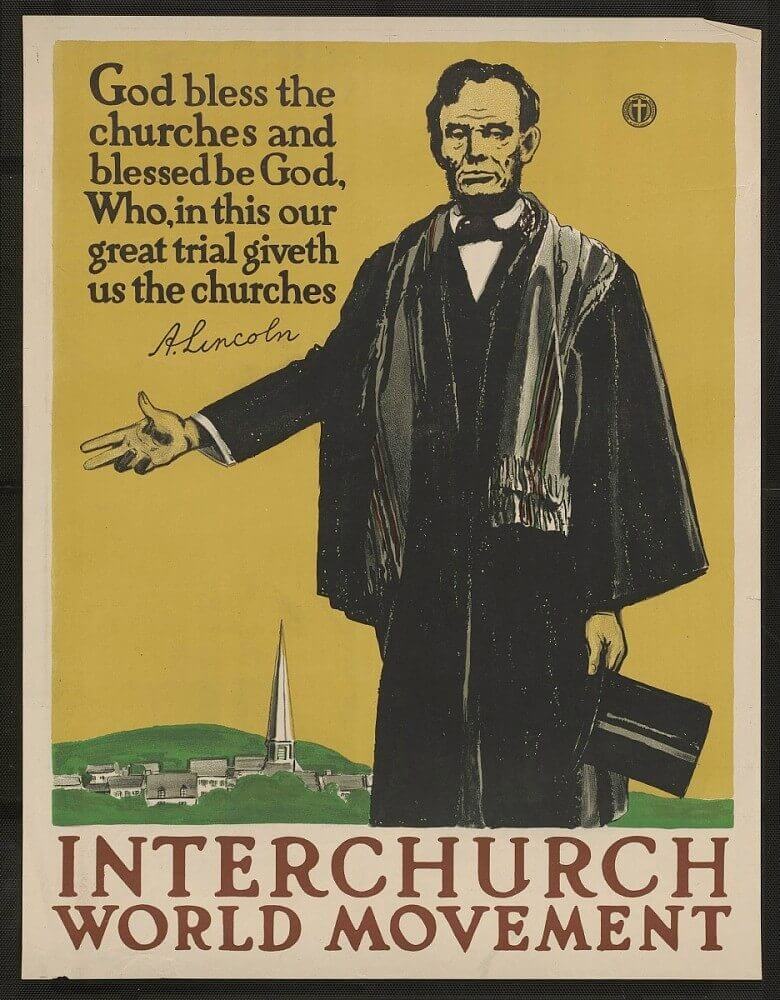

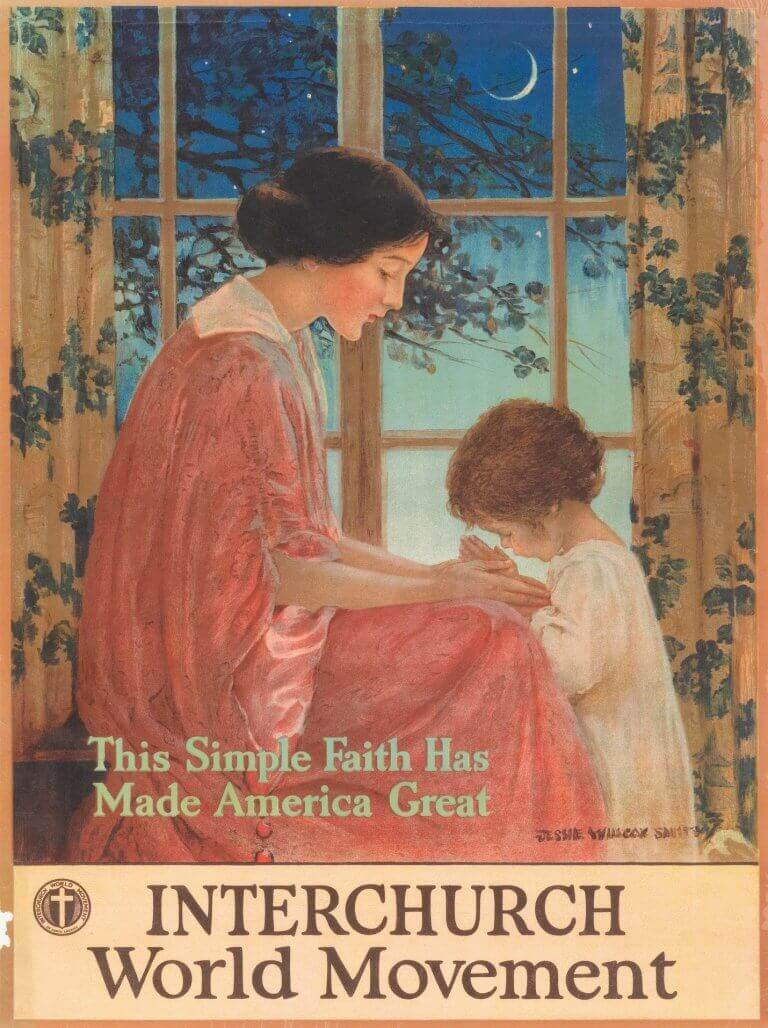

While workers were out on strike during the winter of 1919-1920, John D. Rockefeller invested an estimated $25 million dollars to the Federal Council of Churches for the evangelistic campaign called the Interchurch World Movement. This was a massive evangelistic campaign designed to detract media attention from the strikers and celebrate the good “Christian values” of temperance, financial stewardship, and regular church attendance. Rockefeller’s money paid for celebrity speakers, musicians, acting troupes, clergy, and entertainers of every variety to leaflet steel towns and invite workers to Christian revivals. Revivalists reminded workers of the importance of temperance and the great “family” centered values of US Steel. By January, this evangelistic campaign had run out of money and the Federal Council of Churches recognized that they turned over too much authority and power to lay businessmen to execute their church affairs. But, the union had been defeated and Rockefeller’s goals had been accomplished.

A few months later, several ministers within the Federal Council of Churches published a “strike report” with the Bureau of Industrial Research which did recognize that workers were severely underpaid relative to the actual cost of living in the steel towns. However, this strike report—like all Federal Council strike reports—arrived too late to be actually helpful at the bargaining table. It also made no substantial effort to support the most important goal of the strike—the right of workers to free speech and their own independent voice through collective bargaining. Rockefeller’s campaign ushered in a new discourse around labor and Christianity which stood against unionization and social democracy.

Wait a minute. Are you saying the leaders of the Federal Council of Churches were fundamentalists? I thought fundamentalists were the folks opposed to the Protestant liberals leading the Federal Council of Churches.

Good question. This is confusing. I argue that the Social Gospel movement was a forerunner to the Fundamentalist movement in its efforts to restrain and control the widespread popularity of heterodox Christianities popular among the working classes. Within the Federal Council’s “Social Service” messaging of the period 1908-1918, clergy tried to reassure workers that they were allies in the struggle for labor justice. During World War I, as the number of organized workers grew exponentially and clergy became less crucial to addressing the industrial conflict, the Federal Council took a step back from their alliances with workers and tried to cultivate their own authority to dictate industrial justice.

The Interchurch World Movement, a subsidiary of the Federal Council of Churches that only lasted about a year (1919-1920), popularized many of the central ideas that would materialize in the fundamentalist movement of the 1920s. These “Christian ideals” included personal responsibility, anti-socialism, patriarchal family values, and the importance of church-attendance. Above all, the Interchurch World Movement recentered the importance of personal sin and personal salvation. With the support of Rockefeller and the Federal Council itself, these new “Christian ideals” moved the whole Social Gospel movement away from support for labor.

Interchurch World Movement Poster, 1919. Credit: National Museum of American History.

Interchurch World Movement Poster, 1919. Credit: National Museum of American History.The Federal Council of Churches that reconstituted itself in the 1920s was different from the many versions of the organization that existed before the war. A large number of member clergy came to believe the accusations that the Federal Council was harboring “radicals” and left the organization. Others remained, but the organization operated within a much more racist and openly anti-labor climate. Charles Stelzle is one example of a Social Gospel leader whose ministry had long foreshadowed this fundamentalist turn in church life. Stelzle served as a “ministerial delegate” to the American Federation of Labor in the first decade of the twentieth century and mastermind behind the Men and Religion Forward Movement (sometimes called “Labor Forward” movements) in 1911-1912. He was very active in helping the AFL gain card-carrying members. But, like a good fraction of the AFL leadership, he was doggedly against socialism. Stelzle was a graduate of Moody Bible Institute and a big supporter of the doctrines of personal sin, personal salvation, and the spirituality of the church. He thought of unions as social clubs which could collectively request better wages and working conditions, but he did not want to see them exercising any independent authority within collective bargaining. Stelzle left the ministry in the early 1920s, disenchanted with the Presybterian missionary enterprise that he thought he knew. His story offers a small glimpse of the steady rise of anti-labor Christianities in that took hold of the well-resourced denominations in the 1920s.

Some left-leaning Christian leaders like Norman Thomas and A.J. Muste left the clerical life and maintained the fight for social democracy. But, as I say at the end of the book, the bulk of Protestant Social Gospel liberals defended welfare capitalism, accepted the persistence of Jim Crow, and supported overseas colonization. That is, they did not stand with social democrats. While the Social Gospel movement accomplished very little in terms of support for workers, the movement was quite successful in creating a narrative of Christian Social Service that retrospectively anointed Protestant ministers as heroes to the working classes.

Now that your book is published, what books are you looking forward to read?

What a fun question!

I can’t wait to read Jon Shelton’s The Education Myth: How Human Capital Triumphed Social Democracy, Jefferson Cowie’s Freedom’s Dominion, Aimee Loiselle’s Beyond Norma Rae: How Puerto Rican and Southern White Women Fought for a Place in the American Working Class, and Heather Cox Richardson’s Democracy Awakening. I also can’t wait to read your book on Rabbi Stephen Wise, whenever it becomes available!

I am also hard at work on an incredibly immersive new project, which is loads of fun. I’ll have to tell you about sometime!