Kevin Kenny, a noted scholar of labor history and immigration history, has recently published The Problem of Immigration in a Slaveholding Republic: Policing Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Oxford University Press 2023) which “explains how the existence, abolition, and legacies of slavery shaped American immigration policy as it moved from the local to the national level over the course of the nineteenth century.” J. Hollis Harris, a Ph.D. candidate at Northern Illinois University, interviewed him about his book.

While it is clear that The Problem of Immigration is not necessarily a classic “labor history,” can you offer a few reasons labor historians might want to pick up your book?

Having spent most of my career writing history from the bottom up, I adopted a top-down perspective in this book because of the nature of the question I was addressing: Who claims authority over human mobility, and on what grounds? This approach required me to move away from social history toward legal, constitutional, and political history in ways I had not done before. Yet immigration history and labor history are inseparable, and the book directly addresses labor in several ways.

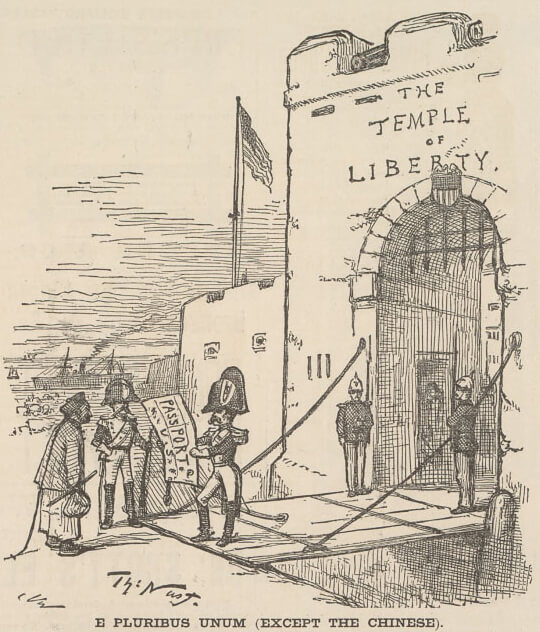

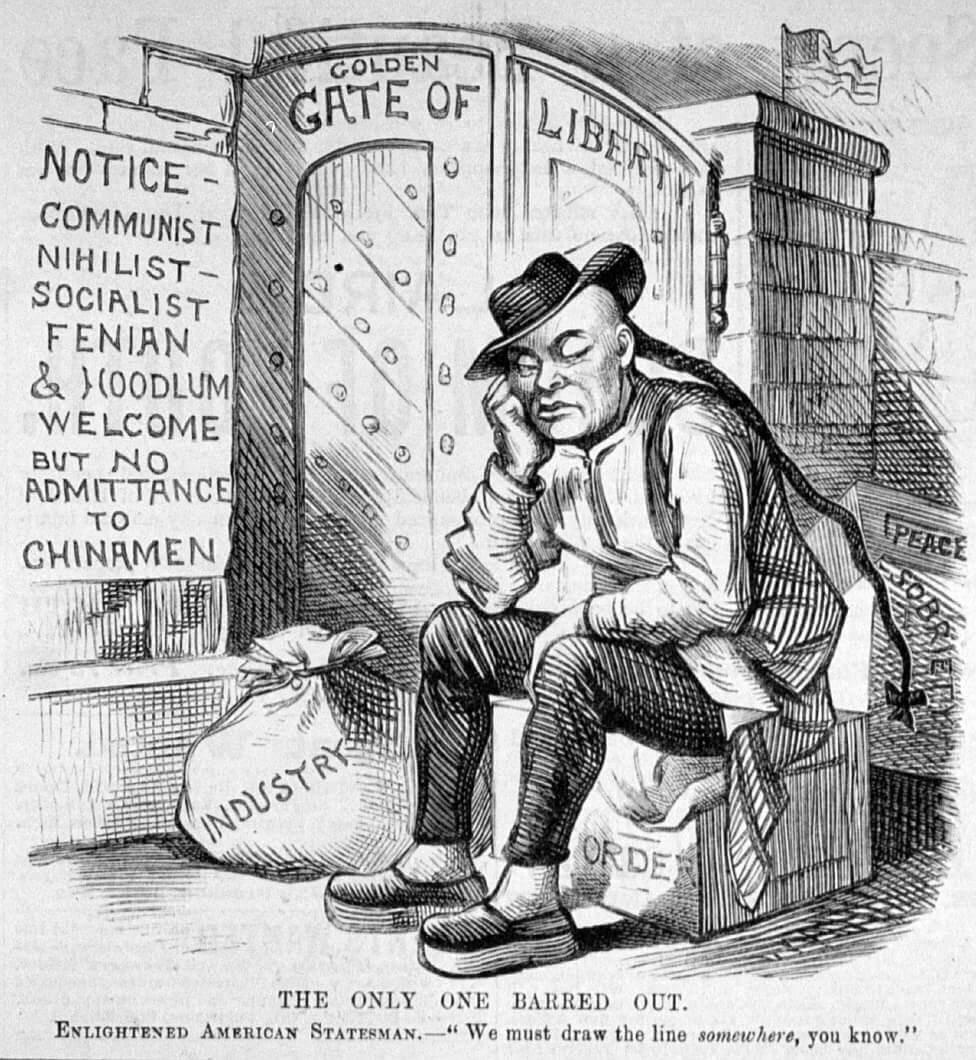

The question of contract labor is central to the argument, beginning with legislation passed during the Civil War. In 1862 Congress passed a law prohibiting the so-called coolie trade, equating the transportation of certain Chinese laborers with slavery. This law applied to American involvement in the transportation of coolies to Cuba and Peru and had no direct impact on Chinese laborers immigrating to the American West, whom it classified as free. Over the next twenty years, however, restrictionists in the United States accused all Chinese laborers of being coolies and insisted that, as the equivalent of slaves, they should be excluded from the United States—a campaign that reached fruition in 1882–92 with Chinese exclusion. In contrast to the Chinese case, a second measure passed during the Civil War, the Act to Encourage Immigration (1864), lent federal recognition to the recruitment of European workers on short-term contracts. This law generated opposition to immigrant contract labor, culminating in the Foran Act of 1885, which prohibited immigrants from entering the United States under contracts signed abroad. Supporters of the Foran Act, drawing on the precedent of Chinese exclusion, framed it as an antislavery measure targeting what they saw as the European (especially Italian) equivalent of coolie labor. The upshot of these various measures was to cast Asian migration as inherently unfree and white European workers, liberated from the shackles of contract, as America’s archetypal immigrants. The categories of supposedly free and unfree labor, in other words, were created through government regulation.

Can you elaborate on how your book intervenes in an understanding of labor and the Chinese question, especially the issue of employers preferences for some Chinese laborers but not others and the way this dynamic played out in labor politics?

Historians have studied this topic very intensively—including labor historians such as Alexander Saxton in The Indispensable Enemy (1975) and, most recently, Mae Ngai in The Chinese Question (2022). Saxton focused on the exclusionists rather than on Chinese immigrants, but his work offers enduring insights on labor politics and ideology; Ngai explains the various kinds of work Chinese immigrants did, along with the different exclusionist logics that emerged in countries around the world (based, for example, on slavery or empire) and their eventual convergence in an international anti-Chinese ideology. Drawing on the work of these two historians, work by Erika Lee and Beth Lew-Williams’s, and my own research, I explain how railroad interests—who benefited from inexpensive, exploitable labor—initially opposed Chinese exclusion, while Dennis Kearney’s Workingmen’s Party, as is well known, spearheaded the exclusion movement as part of radical but racist critique of monopoly capitalism. If there is an original twist to my retelling of this story, it lies in what I call the antislavery origins of US immigration policy. Chinese exclusion, I show, rested on a twisted reading of the Thirteenth Amendment, which produced the following syllogism: slavery was prohibited in the United States; all Chinese laborers were coolies, and all coolies were slaves; therefore, Chinese laborers must be excluded. This form of racism was even dressed up as humanitarianism, with the Chinese supposedly being excluded for their own good.

Throughout The Problem of Immigration, I sensed that efforts to control the movement of enslaved people, free Black folks, Chinese immigrants, and others were consistently motivated by their potential impact as workers in a given labor market. Would you say that defining national sovereignty is as much about a nation’s efforts to control peoples’ labor as it is about a nation’s ability to police their mobility? Why or why not?

Wood engraving by Thomas Nast. Harper’s Weekly on April 1, 1882.

Courtesy: Chinese in California Virtual Collection: Selections from the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

The answers to this question vary by group. Labor, class, and poverty also need to be viewed in tandem with several related issues. In the Chinese case, as I have just discussed, labor was an overriding concern. Chinese exclusion emanated in large part from protests by organized white labor; yet it was explicitly based on class as well as race, targeting laborers (both skilled and unskilled) while exempting merchants, students, and teachers. Irish immigrants, meanwhile, endured considerable bigotry and prejudice throughout the nineteenth century but they could enter the country, move from state to state, get jobs, testify freely in court, naturalize as citizens, vote, and hold political office—things that most Chinese immigrants and most African Americans, free or enslaved, could not do. From the legal, constitutional, and political perspective that I adopt in this book, there is no doubt on which side of the color line the Irish stood. Nativists petitioned Congress to place restrictions on immigration by Irish paupers and demanded that the waiting period for naturalization be extended from five to twenty-one years. But Congress took no action. Demand for Irish labor was too high for restriction to make sense. Even in Massachusetts, where anti-Irish nativism was strongest, the most the Know-Nothings could achieve was to impose a temporary two-year delay on voting. Nobody called for numerical restrictions on European immigration before the end of the nineteenth century.

In the African American case, chattel slavery was, fundamentally, a labor system designed to produce commodities. My book, however, does not attempt to retell the labor and social history of slavery. It examines the enforcement of fugitive slave laws, constitutional and political battles over the external and internal slave trade, and—above all—regulations on the mobility of free Black people, whose very presence contradicted the racial logic of slavery. In the South, the primary rationale for policing free Black people moving into, within, and across state borders was to protect the institution of slavery from what contemporaries referred to as “moral contagion”—i.e., the fear that they would provoke discontent or even rebellion. In the Old Northwest, similar laws instilled a sense of stigma and shame even when laxly enforced. Given that chattel slavery in the United States was a massive system of exploited labor, one could argue that it all came down to labor in the end, but I do not make that argument explicitly in the book.

Finally, an important part of my argument is that plenary power over immigration—a power held to be inherent in national sovereignty and largely immune from judicial review—emerged in tandem with and based partly on precedents set in federal Indian policy. Indian Removal, in itself, was obviously not a labor issue. Yet this process of forcible expulsion and extermination had major implications for slavery, enabling the rise of the Cotton Kingdom in the early nineteenth century.

The subtitle of your book is “Policing Mobility in the Nineteenth Century United States.” Certainly, there is a history of policing enslaved people and the construction of vagrancy laws for workers in the nineteenth century. How does your book contribute to understanding how policing mobility created immigration law?

In a slaveholding republic with sovereignty divided between the states and the national government, mechanisms for controlling the mobility of different groups of people were closely interrelated. In particular, control over foreign immigration in the nineteenth century was inseparable from mechanisms regulating the mobility of free Black people and other poor people. The constitutional right to move freely from state to state was not widely recognized until the twentieth century, and even then Black people continued to face severe constraints by law and in social practice.

For the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, the federal government played almost no role in regulating the admission, exclusion, or removal of foreigners. Under the Constitution, each state retained sovereignty over matters on which it had not surrendered power to the national government. Towns and states used their police power to regulate mobility. Today, the term police refers to a body of people charged with keeping public order and investigating crimes. In the nineteenth century, however, “police” had a related but broader meaning, referring to the right of local communities to regulate the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of their residents. State and local governments passed quarantine laws; required ship captains to post bonds or pay taxes for foreign paupers and others who might require public support; patrolled the movement of free and enslaved Black people; and jailed free Black sailors, both native-born and foreign-born, for the duration of their stay in southern ports. They insisted that it was their right and obligation to protect public health and safety in this way.

State-level policies regulating immigration and other kinds of mobility emerged in part from the poor law system. Local laws requiring bonds or taxes for alien passengers were designed, for the most part, not to exclude immigrants but to raise revenue for the upkeep of the poor. Poor laws provided for the removal of paupers out of state or even—in the case of Massachusetts—out of the country. Only very rarely, however, did these laws exclude immigrants from entry. Nearly all European immigrants were admitted, as long as ship captains paid the required taxes or fees (raising fares accordingly). States used their poor law system even more extensively to regulate free Black people, who—unlike European immigrants—faced severe constraints on their mobility within and between the states despite being born on American soil.

The constitutional battle over mobility in the nineteenth century pitted federal commerce power against local police power. Which level of government had authority, local or national? The Supreme Court was unable to resolve this question before the Civil War. If federal courts invalidated state imposing taxes or bonds on foreign paupers, what were the implications for similar laws punishing free Black seamen, laws in Southern states expelling emancipated slaves, or laws in both the North and the South barring the entry of free Black people? It took a war and the abolition of slavery to remove the constitutional and political obstacles to a national immigration policy, which emerged in response to the perceived threat of Chinese migrant labor.

Most current treatments of immigration restriction start with the Exclusion Acts beginning in 1882 and their pre-history. Hidetaka Hirota (Expelling the Poor) urged an interpretation that linked Irish immigration at the state level as precursors to federal restrictions that excluded the poor. How is this book in dialog with his findings? Where do the Irish waves of immigration and the development of the “Public Charge Rule” fit in against the backdrop of political struggles to define participation in the U.S.’ political community?

Hidetaka Hirota wrote his doctoral dissertation under my supervision and I learned a great deal from working with him. He began with a compelling question. What was the practical impact of nativism in the nineteenth century? Not content to approach nativism as a body of bigoted ideas, Hirota wanted to know if these ideas translated into laws and policy. In the answering this question, he proposed a new explanation for the origins of national immigration policy in the United States. While in no way denying the importance of anti-Chinese racism in the emergence of this policy, Hirota showed that economics, class, and poverty in the eastern seaboard states were central to the story. When the federal government passed its first general immigration law in 1882—the “moment of transition,” as Hirota calls it in his book—state officials designed and implemented the law, including a head tax on passengers and a public charge rule based directly on the old system of local immigration control that the Supreme Court invalidated in 1875.

Without disagreeing with any of these findings, I shift attention in my book back to race. Even in the absence of slavery, the United States would have developed a national immigration policy, as other countries did. My argument, however, is that the existence, abolition, and legacies of slavery shaped the emergence of that policy at almost every stage along the way.

Hirota wrote a lot about Irish poverty, as I have done in my previous work. From a legal, constitutional, and political standpoint, Irish immigrants had no need to become white. They were white the moment they arrived in the distinctive racial hierarchy of the nineteenth-century United States. In saying this, I am not downplaying the viciousness of anti-Irish sentiment. Nativists despised the Irish for their poverty, religion, manners, and morals, but in a context where chattel slavery defined race, describing this prejudice as racist drains that term of meaning. To “become white,” Irish immigrants would first have had to be assigned to some prior racial category, yet the historical evidence does not support that contention. Irish immigrant workers led violent racist attacks on African Americans and Chinese immigrants. When it comes to anti-Irish prejudice, however, class and religion provide adequate explanations.

The conclusion ends on an extremely prescient discussion of modern citizenship rights, seen through the concepts of jus soli (right of the soil, or birthright citizenship) and jus sanguinis (right of the blood, or law of descent). Personally, I see your well-reasoned call to defend birthright citizenship as indicating a deeper political motivation for writing The Problem of Immigration. If I am correct, do you care to expand on it here?

I researched and wrote most of this book in the worst days of the Trump administration and Brexit, both of which rested on a severe backlash against immigrants. Trumpism hardly needs rehearsal here; the deepest desire of the Brexiteers was to curtail human mobility—a remarkable desire to cherish if you step back and think about it. Support for Brexit was highest in areas of Britain that had the fewest immigrants and received the most support from the EU. Yet, just as in the United States, the anti-immigrant backlash worked, because it provided a scapegoat for the massive, entrenched inequality that lies at the heart of the current political crisis in both countries.

International border controls of some kind are here to stay, but where did they come from and on what claim to authority do they rest? Why, how, and on what grounds did some Americans claim control over the mobility of others, whether enslaved people, free Black people, immigrants, or Indigenous people? That is the question at the heart of my book. When it comes to federal immigration policy, as the book reveals, plenary power over immigration rested on starkly racist grounds, emerging directly from Chinese exclusion. As recently as 2018 in Trump v. Hawaii, the Supreme Court upheld Trump’s so-called Muslim travel ban by citing The Chinese Exclusion Case (1889). National security, then as now, justifies sweeping power over immigrant admissions and expulsions, largely immune from judicial review. Yet, even if immigration does raise some security questions, most people migrate because they are driven out of their home counties or because they hope to build better lives abroad. Might that not suggest alternative rationales for regulating their mobility?

Once immigrants settle in the United States, they enjoy fundamental rights. The Fourteenth Amendment, with its guarantees of due process and equal protection, applies not just to citizens but to all persons living under the jurisdiction of the United States. The children of all immigrants, moreover, are citizens by birthright. In a world where most countries continue to impose qualifications for citizenship—based on ascriptive categories of descent, race, religion, or gender—the United States follows a strikingly liberal policy of jus soli rather than jus sanguinis. Forged in a war to end slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment provided a highly effective way of integrating immigrants and their children.

Birthright citizenship is under threat today, with nativists implausibly but insistently questioning whether the American-born children of unsanctioned immigrants are properly “under the jurisdiction” of the United States or whether they owe their allegiance to a foreign power. Fortunately, any attempt to dismantle the Fourteenth Amendment would require the Constitution itself to be amended, and this is unlikely to happen. Nor would an executive order pass muster. In the meantime, however, states may pass measures restricting access to local citizenship.

This brings me to my final point, the continuing relevance of immigration federalism today. As a historian of the nineteenth century, I don’t usually end my books with a protracted reflection on contemporary issues. For this book, however, I wrote an epilogue taking the story up to the present, because of the salience of the issues. Although the federal government controls immigrant admissions, states and cities continue to regulate the lives of immigrants through their police power once they have entered the country. They play a double-edged role in this respect, depending on their location and politics. Many local jurisdictions pass laws restricting immigrants’ access to public welfare, educational tuition, drivers’ licenses, and employment, along with measures enhancing cooperation with federal agencies like ICE. Others, however, pass pro-immigrant laws facilitating access to benefits, education, and work. Some provide sanctuary against federal surveillance, complementing grassroots efforts by faith-based organizations and other activists.

The parallels with the antebellum era are striking. Northern states provided refuge for fugitive slaves and free Black people in danger of being kidnapped into slavery. They could not obstruct fugitive slave law, but neither were they obliged to enforce that law. Likewise, states and cities today cannot directly defy federal immigration law, but they cannot be ordered to enforce that law. Local sovereignty is not just a matter of autonomy from the federal government; it can also entail an obligation to protect all residents living under a given jurisdiction, regardless of their background or origin. Given the long association of states’ rights with racism in US history, local sovereignty is a thin reed on which to base a progressive politics. Rights can obviously be protected more effectively if defined nationally and guaranteed by the federal government. Yet, at times when the federal government is itself virulently anti-immigrant, local power and resistance can provide some grounds for hope.

Kevin Kenny is Glucksman Professor of History at New York University. His books include Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (Oxford University Press, 1998), The American Irish: A History (Longman, 2000), Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn’s Holy Experiment (Oxford University Press, 2009), and Diaspora: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press 2013). He has published articles in Labor History, the Journal of American History, and the Journal of American Ethnic History, among other venues. Professor Kenny’s latest book, The Problem of Immigration in a Slaveholding Republic: Policing Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Oxford University Press 2023), explains how the existence, abolition, and legacies of slavery shaped American immigration policy as it moved from the local to the national level over the course of the nineteenth century. Oxford will publish a 25th anniversary edition of his first book, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires, in September 2023. Professor Kenny currently serves as President of the Immigration and Ethnic History Society and as a Distinguished Lecturer of the Organization of American Historians.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.