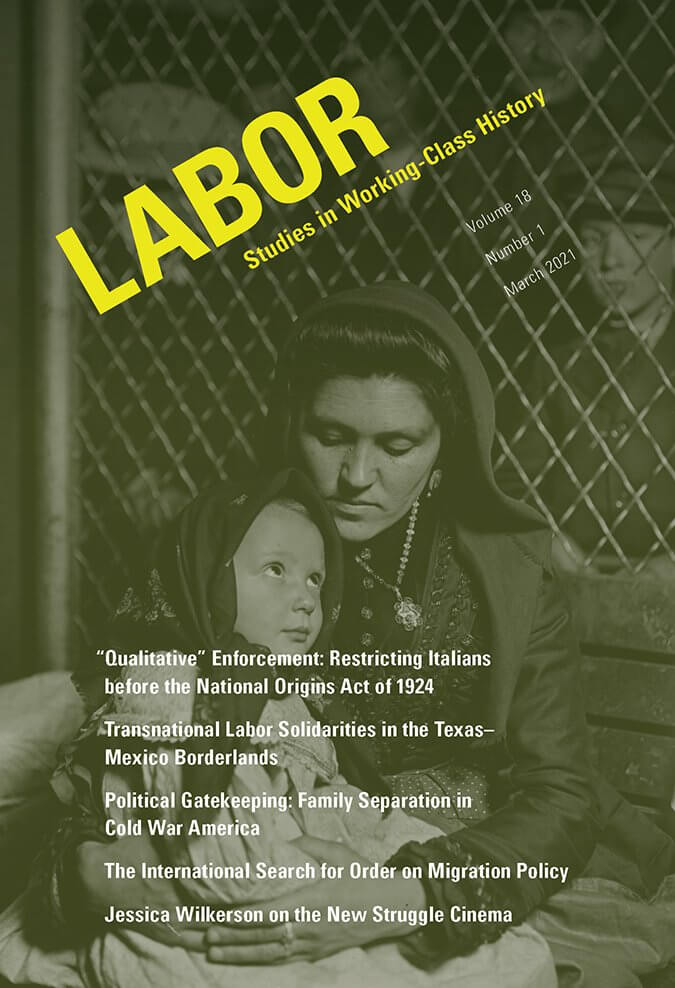

News that hopeful immigrants continue to be transported across the border under the Biden administration at levels last reached in 2018 makes it clear that the early weeks of the new administration will not bring a policy sea-change. And it makes the essays in the new issue of Labor 18:1, which discuss elements of U.S. gatekeeping on working class immigration all that more resonant.

Part of the backstory to gatekeeping against the poor is told brilliantly in an essay by Lauren Braun-Strumfels that Labor has made freely available from behind its paywall for three months: “Binational Gatekeepers: The Italian Government and US Border Enforcement in the 1890s”

U.S. immigration gatekeeping policy was not only racialized through anti-Chinese provisions, politicized through provisions that began to target immigrant radicals from exclusion, but also targeted the poorest for exclusion. Hidetaka Hirota’s recent book Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of American Immigration Policy tracked how this policy developed at the state level in respect to Irish immigration. Massachusetts and New York deported as many as 100,000, especially poor Irish women, to England and Ireland. These policies were initiated by bureaucrats whose stereotypes of the Irish poor were encoded later into the federal law and administrative state. By the 1890s, Braun-Strumfels shows, the words “likely to become a public charge” (LPC) provisions came down on Italians as the new target. Surely we know of the harsh treatment of Italian immigrants who made it through in these years, through the 1930s. But this essay sheds light on the gatekeeping that sent many back home, and the work of state officials on both sides to decide who got in and who did not.

Braun-Strumfels shows how immigration agents in this new era of federal control targeted poor Italian immigrants under the LPC clause, which was never clearly defined, and facilitated the construction of the cages and routes of the rejected back to Italy, even as the numbers of the poor fleeing rural poverty in Italy swelled to Ellis Island. It amounted to tens of thousands even before the 1920s when formal exclusion of Italians (among others) through numerical control took the place of these day-to-day decisions. She writes,

For the United States, as for many other receiving countries at the time, immigration laws became a tool both to shape US society and to establish its right to determine who could (or could not) enter the country and who could naturalize. Chinese were the first targets of immigration restrictions because many Americans saw them as the quintessential “other.” Italians, called “the Chinese of Europe,” became one of the primary targets of nativists’ zeal for restriction. By the beginning of the twentieth century, immigration laws measured and categorized aspiring immigrants by socioeconomic class, literacy, criminality, political beliefs, diplomatic standing, physical and mental health, and sexuality. Officially rejected because they could not guarantee that they would be able to provide for themselves financially, the poor, and unmarried or unaccompanied women, became the primary target for expulsion, making the LPC clause about social control, and further expanding the right of the state to exclude.

The rules and limits of gatekeeping in this early era took old ideas and refreshed them from new sources, even as a refined bureaucracy emerged.

Braun-Strumfels shows that it was not only U.S. agents who claimed the right to assess the poor immigrants. Alarmed by the treatment of their countrymen, agents of the Italian government became the immigrants’ advocates, setting up an unprecedented Office of Labor Information and Protection for Italians from 1894-1899 at the processing building on Ellis Island. But this vaunted position forced them to comply with some of the assessments set out by the U.S. agents. The agenda to weed out immigrants before they migrated took hold just as is occurring in Mexico in this historic moment.

Braun-Strumfels’ keen attention to the limits of these Italian agents, as well as their strategy of negotiation on site, shows the middle level bureaucrat at work, even if the sources shield the voices and perspectives of the immigrants themselves. It makes this a fascinating contribution to the labor dimensions of US immigration restrictions.

LAUREN BRAUN-STRUMFELS is associate professor of history at Raritan Valley Community College in New Jersey. She is currently finishing a book on the relationship between Italy and the United States during ten pivotal years, 1891 to 1901, that shaped the practice of American gatekeeping.