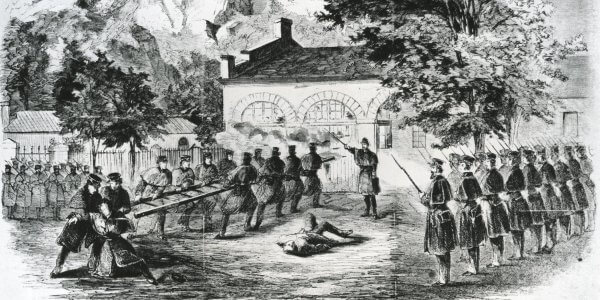

Showtime’s The Good Lord Bird uses the events around John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry to weave a fictional tale incorporating some basic insights and arguments about the nature of race in America. It did its most impressive work in presenting the wide spectrum of diverse African American responses to slavery and, in the process, offering a better sense of their humanity. It does so most clearly in the last part of this seven-part series.

The series is narrated from the perspective of the entirely fictional Henry Shackleford (Joshua Caleb Johnson), a fifteen-year old African-American boy. The story opens in Kansas, where he encounters John Brown (Ethan Hawke) improbably sitting alone in a denizen of pro-slavery thugs, culminating in a shootout in which Henry’s father is killed, and Brown escapes with the boy. Mishearing his name as Henrietta, Brown tries to console the boy by giving him a dress he had gotten for his daughter. Explaining that slaves do not dispute the understanding of whites, Henry accepts this and passes as a girl through most of the series. In turn, the underfed Henry mistakenly assumes that when Brown shows him a little onion that he’s being offered food and hungrily consumes it, winning the nickname “Little Onion.” Of course, these emphasize the grounds for misunderstanding across the barriers of race.

The death of Henry’s father hints at something deeper. Henry remains oddly ambivalent about the risks of being a runaway, and clearly wonders whether abolitionists were making things worse for some blacks. In a particularly cringe-worthy sequence, he describes two snakes “one points south, the other points north,” both poised against blacks. The preoccupation with issues of violence seems anachronistic. To exaggerate the point, the fictionalized Brown explicitly declares his intention to detonate a civil war that would take its toll on every family in the country.

Violence had nothing to do with theological preferences.

The miniseries itself sought to tell a story and portray characters rather than convey history. It begins with a shootout worthy of Silverado and has an ending that recalled Butch and Sundance charging into the courtyard against the army. It passes over much that is necessary to a historical understanding of the subject—that long struggle against slavery, Kansas, and the antislavery electoral insurgency across the nonslaveholding states.[*] The basic demands of self-defense put arms in the hands of antislavery militants, who not only faced extralegal proslavery forces, but the national authorities and the U.S. Army.

Much is sacrificed in the interest of the story. The portrayal of Frederick Douglass, the well-known temperance lecturer, as something of a hard-drinking womanizing dandy; and Hugh Forbes, the Garibaldian founder of what became the International Workingmen’s Association in the U.S. as a thief dismissively misrepresents two of the numerous abolitionists concerns about the wisdom of Brown’s attack on the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

This carries over into the depiction of Brown himself. As a character he has appeared in movies and television, mostly as versions of Raymond Massey’s homicidal madman from Santa Fe Trail (1940) and Seven Angry Men (1955). Usually forgotten is Royal Dano, prophet from The Skin Game (1971), which, to be fair, required only a brief cameo which brings the righteous wrath of God down on a slave auction. Ethan Hawke’s well-delivered new cinematic presentation of Brown certainly offered a sympathetic multi-dimensional character of real depth.

That said, the Brown of The Good Lord Bird mediated without challenging the dismissive slanders about an alleged madness rooted in his monomaniacal religious dogmatism, a reputation that inspired some modern anti-abortionists to brandish his name. The first hours of the miniseries rarely even showed Brown without his ranting about the Bible and pressing those around him to declare fealty. In a low point, he is dropped into a dinner in the home of Frederick Douglass as a boorish oaf annoying the host and his family.

In fact, pious though he was, Brown was no fanatic in that sense. His band included spiritualists, freethinkers, and atheists. Two of his Jewish comrades shouted back and forth in Yiddish over the gunfire at Black Jack. In addition, local Native American leaders sheltered and fed them. Socialists, radical land reformers, and others rode with the band, some of which, with their friends and allies founded the territory’s women’s rights organization. Brown himself delved deeply in the study of slave revolts in antiquity and the successful rebellion in Haiti, and visited Europe in the wake of the 1848-49 revolutions.

Movies, like written histories, are products of the times. Reviewers have couched their discussion of The Good Lord Bird by pointing out its portrayal of history against the backdrop of ongoing protests about persistent racism. However, is also an age that regularly feeds us fictions about the present, at the cost of, in the current pandemic, as many as were killed outright on the battlefields of the Civil War. In the end, The Good Lord Bird spins a worthwhile and entertaining yarn, but each episode starts with the unfortunate and misleading words: “All of this is true. Most of it happened.” Well not historical truth–and what happened often seems to have gotten there like Billy Pilgrim, slipping in and out of time.

Poetic truth is different.

Like Brown, Henry and their comrades, Americans, as a people, share a common fate, regardless of something as trivial as skin pigmentation. The suppression of black votes does not just deny their right to vote but denies the right of each and every American to a representative government. The murder of unarmed African Americans by the police represents an assault by armed authorities on the security of each and every American. Until we—particularly the designated white majority—come to understand that and act accordingly, it behooves us to remember and cherish the legacy of John Brown and his comrades.

Above: The virtuoso Paul Robeson performs John Brown’s Body.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yn9Sr5LMNb4>

[*] Brown and his circle continue to draw biographers: David S. Reynolds, David Blight, Tony Horwitz, Charles P. Polard, Jr.