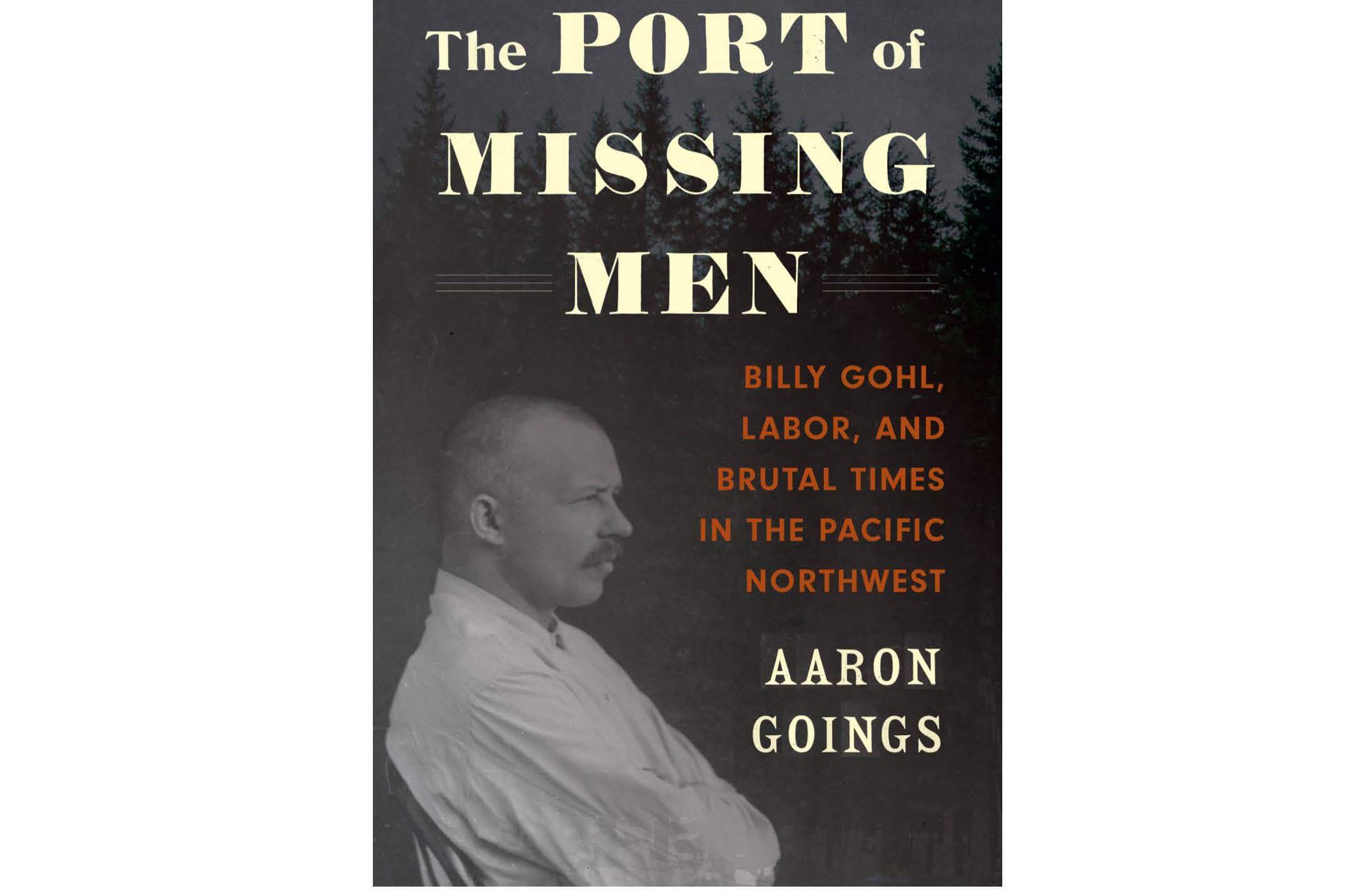

In his fascinating new book, Aaron Goings interrogates the legend of Billy Gohl (1873-1927), a union official accused of dozens of murders. He seeks to bring light to the accusations that have made Gohl a true-crime figure in local popular culture. In doing so, he reaches into the world of the union culture and brutish conditions in the Grays Harbor near Aberdeen, Washington. I interviewed him about some of his findings.

Feurer: Grays Harbor seems an apt name. Your book delves into the gray world of the “floater fleet” (dead bodies in the waters) and a grim view of the port life of the working class in order to question the myth of Billy Gohl. Can you give us a few highlights of that world you depict?

Goings: Thank you, yes, this is a good place to start. Grays Harbor is an ideal name for the setting of this book—if anyone has ever been to Washington’s actual coast, you’ll know that the word “gray” is fitting. Year-round gray skies, gray seas, mist everywhere. Unlike Seattle, which gets less than 40 inches of rain per year, Grays Harbor often gets more than 100 inches in its largest city of Aberdeen, and even more in some rural parts—the rainiest places in the continental United States. Although it’s in the “Evergreen State,” people are far more likely to be struck by the amount of gray all around them.

But it’s another color – Red – that so often shows up in my work. My PhD thesis was titled “Red Harbor,” and my co-authored popular history of western Washington radicalism was titled “The Red Coast,” so the interplay between red (radicalism, violence) and gray (grim, dark, haunting, the presence of death) shape the context.

The “Grays Harbor” name and weather make for a useful reflection of the region’s social and political history. Grays Harbor sits at the southwest corner of the Olympic Peninsula. When industrial logging and sawmilling started, the region was home to some of the world’s largest trees and densest forests. The wood products industry that developed there – logging, sawmilling and shingle manufacturing, as well as maritime transport of lumber – was central to every aspect of the region’s history. Scores of historians have discussed the dangers and terrible conditions faced by lumber and maritime workers. Historian Erik Loomis is the most recent scholar to probe the varied risks of lumbering; loggers and sawmill workers walked into work each day not knowing if they would survive the day.

These industries birthed some of North America’s most militant and vibrant labor movements. From 1900 to at least 1940, Grays Harbor was an important base for these unions and left movements. The Grays Harbor of Billy Gohl was the most densely unionized part of Washington State. Workers, from teamsters to restaurant workers, plumbers to laundry workers, had unions. But, during the early 20th century, no lumber workers (except those in red cedar shingle manufacturing) were unionized, so no part of organized labor presented much of a threat to the largest—really, the defining—industry of the Harbor and Pacific Northwest. The exceptions to this rule were the maritime workers, especially the strong and often militant Sailors’ Union of the Pacific (SUP), and at other times the famed militant longshoremen’s unions.

In Grays Harbor, unionized seamen elected Gohl their sole local representative—their union agent—between 1903 and 1910. Gohl’s fellow unionists twice elected him president of the local labor council and the founding president of the Grays Harbor Waterfront Federation (GHWFF), a group of the region’s most militant unions formed to contest the power of lumber industry employers. Gohl’s activism, though, extended well beyond the shop floor, as the union agent was a community activist committed to improving the lives of maritime workers and making the local waterfront safer. He was easily the most notable local labor unionist of his era—and his union had the power to tie up Grays Harbor’s prolific lumber port.

You write that “if there was a Ghoul of Grays Harbor, then he wore a top hat and frequented the halls of the chamber of commerce and state legislature.” Can you elaborate, and help us understand how the lens of labor history helps to question the myth of Billy Gohl as mass murderer?

Right, so to no one’s surprise, Billy Gohl isn’t famous because of his labor or community activism. Anyone who has heard or read his name likely associates it with the word “murderer.” The “Ghoul of Grays Harbor” myth asserts that Billy Gohl was one of the country’s most deadly serial killers, responsible for murdering dozens of workers—mostly itinerant laborers—during the early 20th century. Like most myths, I suppose, within this one lies a kernel of truth. Much of the notoriety around Gohl – and “the Ghoul of Grays Harbor” comes from the fact that Grays Harbor was a very dangerous place during the early 20th century. The problem with the mythical version of Grays Harbor violence is that it punches downward—blaming an individual worker (Gohl), who also happens to be the most notable local labor leader—rather than seeing structural forces of violence. It’s somewhat silly to believe that Gohl killed dozens (or hundreds) of people—but hundreds were killed by the engines and the saws of capitalism.

It’s certainly true that the Harbor was a tough place to live. Workers never knew if one day would be their last. Both during Gohl’s time in Aberdeen, and for years after, the city led the Pacific Northwest in violent deaths. What’s more, most wage laborers in Grays Harbor worked in lumber, which was also the Pacific Northwest’s most dangerous industry. Logging, sawmill work, and shingle manufacturing killed and maimed hundreds of Grays Harborites during Gohl’s time as union leader.

The line that you quoted: Yes, I am saying that bosses and their allies in government and the press were responsible for making Grays Harbor a dangerous place. Of course, the bank presidents and mill owners didn’t walk around actively killing people. That wasn’t their M.O. What labor history helps us see is that there are bigger structural forces at work, making Grays Harbor and the wider Pacific Northwest “brutal” places. What’s more, the legal system allowed the wealthiest residents and their associates to act with impunity when they did commit interpersonal acts of violence, especially when their chambers of commerce and elite fraternal clubs transitioned into citizens’ committees: those notorious union-busting groups that used vigilantism and sometimes hatched plots to achieve their goals.

At least 4 types of boss violence stand out to me:

First, employers’ property on the job killed the most workers. Falling trees and loads of lumber, spinning saws and poorly maintained ships and lumber docks cost dozens of Grays Harbor workers their lives each year. Employers in lumber and maritime fought tooth-and-nail to prevent the Washington State legislature or unions from passing safety measures. Those same employers also passed laws locally and at the state/national levels to prevent workers from organizing, striking, and protesting. Not long after Gohl went to prison in 1910, the city of Aberdeen banned left-wing street speeches—which triggered an IWW free speech fight in 1911-1912. Later in the decade, Grays Harbor bosses applied tremendous pressure on state lawmakers and the governor to pass Washington’s criminal syndicalism act, which essentially banned participation in IWW activities.

Second, the community was unsafe. Those with the most power – employers and politicians – did little to improve public safety. Gohl, on the other hand, was Grays Harbor’s most vocal advocate for workplace and public safety. Gohl demanded ship captains and owners follow the law and union contracts. He publicly condemned those who shanghaied (kidnapped) workers and operated unsafe workplaces. Gohl likewise dedicated his life to making public spaces safer and healthier. He knew full well that environmental and public health issues disproportionately impacted workers and working-class spaces. Gohl wrote articles and delivered speeches condemning the employers, saloon owners, and boardinghouse keepers who grew rich by exploiting migratory workers. Billy wanted the waterfront – the spaces occupied by workers – to be safer, guarded against those who prey upon poor folks. He helped build shacks alongside Grays Harbor waterways so that migratory workers – who because their worklives frequently experienced homelessness – had places to live. Unlike the bosses and their politician allies, Gohl worked overtime to improve community safety.

Third, as I talk about in detail elsewhere, Grays Harbor’s chamber of commerce crowd sometimes responded to union and leftist organizing with violence, mass arrests, deportations, and property destruction. They also imported strikebreakers and brought in the National Guard, on occasion, to crush strikes. These were white men who saw themselves as community leaders, and who welcomed the opportunity to defend that control using whatever means necessary. It’s worth noting that these same bosses hired spies—often from notorious detective agencies like the Pinkertons and Thiels—to spy upon workers and sometimes to manufacture evidence against activists. As it is today, during Gohl’s life, being a working-class activist was dangerous business. Through spies, bosses monitored organizers’ activities and fired them from their jobs. On occasion, as with Gohl, those spies also gathered—really, manufactured—evidence to make sure that union activists were silenced.

Finally, and at the core of The Port of Missing Men, the men wearing top hats and socializing in the halls of power had tremendous control over the lives of others. In the case of Gohl, as in the case of so many labor and social movement leaders, powerful enemies conspired to have him removed, to have him silenced. Gohl spent his 7 years on the Harbor advocating for the types of workplace and community reforms that he thought would make the area safer—helping to curb the violence that, tragically, would later be blamed on Gohl himself. By making sure Gohl would be sent off to prison-based in part on evidence cooked up by labor spies, men from the chamber of commerce ensured that the real Ghoul of Grays Harbor (unsafe living and working conditions, unchecked vigilantism and strikebreaking) could continue unchecked.

Your book seems like an attempt to humanize the “walking delegate,” a role that has been well-criticized by the left-wing interpretations. Could you tell us a bit more about how you worked with the materials to create a fuller picture of Gohl’s role in policing the waters and decks, the saloons and shanties of Grays Harbor?

Right—and those interpretations are useful. Scholars of labor and the left have long viewed walking delegates as “petty grafters and despots,” in Michael Kazin’s words. Walking delegates have also long been a favored punching bag for right-wing anti-unionists and elite progressives who pillory these working people for corruption and “misleading” unionists and workers more broadly.

Billy Gohl was the union agent in Aberdeen (Grays Harbor) for more than six years, and many of his duties were those of a walking delegate. He monitored working conditions aboard ships, made sure all sailors paid dues, called strikes, and kept union sailors away from the infamous “death ships.” Following Billy Gohl’s worklife over several years allows us to see just what a big – and tough – job that was. A short list of Gohl’s duties included assigning unionists to ships to transport the world’s largest lumber port, finding beneficiaries for union death benefits, and arranging and paying for union members’ funerals. According to Billy’s own records, he coordinated dozens of SUP members’ funerals between 1903 and 1910. He also represented unionists in court, translated for the mostly immigrant union membership, and helped provide housing for those without homes.

His work as union officer was especially critical because SUP members were migratory laborers. They traveled between ports and lacked permanent homes. Most resided in boardinghouses, aboard ships, or (at least in Aberdeen) in one of the shacks Gohl helped them build and maintain. While at work, most seamen were essentially homeless. Union agents were the rare allies for sailors when in port, and most everyone else was either dangerous (especially police) or indifferent (most of the population).

Evidence of Gohl’s dedication to his fellow unionists appear throughout the historical record, it’s just that those interested in “the Ghoul of Grays Harbor” story haven’t considered his actual life and activism important. I spent parts of the last 20 years – roughly half of my life – combing through every available newspaper microfilm reel and archival collection. Gohl, the union activist, shows up planning Labor Day events and unionists’ funerals, advocating for worker protections at the legislature and in the city council. In 1906, especially, he ended up in court, charged and convicted of a serious crime for leading groups of unionists in armed battles with bosses and strikebreakers. One of the biggest sources of evidence comes from Gohl’s many letters to newspaper editors, where he discussed the problems facing sailors and advocating for more humane treatment of the men he called “comrades.”

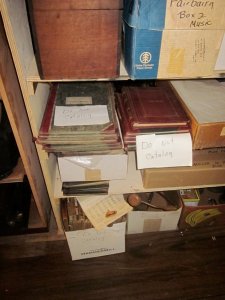

In short, Billy was a busy and dedicated guy, and I compiled a mountain of evidence showing just how devoted to his work—and his fellow SUP members—he was. But, in a sad incident, some of the evidence about Gohl’s worklife—and far more about the region’s labor history—went up in flames during a museum fire in Aberdeen in the summer of 2018. The massive collections of labor history documents – one of the biggest in the Pacific Northwest – was turned to ash. The museum had not cataloged or copied any of these materials, so what we’re left with are fragments of a region’s rich history of working-class activism. The Port of Missing Men and my other writings are an effort to make sure that this region’s history of working-class activism doesn’t end up in the wastebin.

Perhaps part of my sympathy for walking delegates comes from my background. Growing up in a mill town and seeing most of my family (including me) work in mills, I’ve seen the dictatorship of industry first-hand. I’ve also long been impressed with those who advocate for working-class interests on the shop floor—union officers and shop stewards. I have at least some understanding of (and sympathy for) how difficult it is to be a worker and to be tasked with standing up to the boss. It puts a bullseye on a rank-and-file unionist or union agent – and of course on non-union workers who push back against bosses. It’s dangerous business in the 21st century – as it was in the 20th century – and it’s worth remembering that unionists are just people, warts and all. Gohl was a human being, a white working-class man and an immigrant union member and officer. His life was important, and working people deserve to be remembered as human beings rather than ridiculous caricatures crafted by their class enemies.

What do you see as The Port of Missing Men’s contribution to building our understanding of how capitalist conspiracy cases worked in this era?

Billy Gohl and his fellow unionists threatened employers’ profits, as well as their control over the waterfront and wider community. For these reasons, he was the subject of a conspiracy by his class enemies: bosses, wealthy politicians, newspaper editors, who were all members of the same fraternal and business clubs. These men (and they were all men) formed a citizens’ committee and funneled thousands of dollars to the Thiel Detective Agency, perhaps the west’s best-known labor spy agency. Thiel spies and local employers spent much of 1909 and 1910 working overtime to guarantee that Gohl would be arrested and convicted of murder. At the same time, the local press conveniently printed every imaginable rumor uttered about Gohl and his fellow unionists’ alleged criminal acts. In the eyes of the mainstream press, the Sailors’ Union became a criminal enterprise—“Gohl and his Gang.”

It’s also worth noting that this same group – bosses, politicians, editors – had a long history of cooperating in pursuit of their shared class interests. In 1911-1912, this became painfully obvious when these men formed a vigilante citizens’ committee to brutalize Wobbly free speech fighters and strikers. In later years, some of these men formed new groups, including locals of the Ku Klux Klan, to intimidate workers—especially immigrants and Communists.

Thousands of labor histories discuss strikebreaking and wider methods of union-busting. Of course, police rounded up strikers and union organizers, and charged them with all manner of crimes, real and imagined. At another level, we have the cases of the Haymarket martyrs, Joe Hill, Sacco and Vanzetti, and others, where it’s clear there was coordination between employers, police, and courts to bring about “the right” outcome—in those instances, the execution of working-class radicals.

The Port of Missing Men examines a local capitalist conspiracy in detail. It’s not much of a stretch to think that there are plenty more conspiracies—criminal convictions that are either forgotten or are assumed to be a correct – “a just” – outcome. These “conspiracies” are little more than employers colluding with the state (and usually outside forces such as spies) to have a worker or workers removed from public life.

Labor historians can’t possibly trace all the times an important activist got arrested and imprisoned under suspicious circumstances, but it’s worth remembering that any time a militant or radical labor leader was removed from public, bosses had cause to celebrate. The ubiquitous presence of labor spies—especially in union hotbeds like Grays Harbor or hundreds of other cities and towns – makes it all the more likely that a seemingly simple criminal conviction for, say, robbery or assault, perhaps has more to the story. And, one of the many things made abundantly clear by the uprisings of 2020 is that police are all too willing to weave whatever story is in their individual and collective (as police) best interest.

I spent a little time exploring the internet’s version of Billy “Ghoul” and it’s certainly entertaining. Do you think your book will be able to counter that drama?

A first-time Gohl searcher. I’m not sure whether to reply with pity or envy.

I would be very surprised if people stopped telling the Gohl as serial killer story anytime soon. I don’t think “true crime” has ever been more popular, and an army of Internet sleuths will continue to write – and podcast – about their findings. Just to give you an idea of what I’m up against: in the past 3 weeks, I’ve received an inquiry about Gohl from the hosts of a true crime podcast that certainly want to talk about Gohl as serial killer, and an email from a high school student asking me directly: “How many people did Billy Gohl murder?” A member of a Northwest metal band wrote me to let me know they were working on a song about “Billy Gohl the serial killer.” Unfortunately for Billy’s memory, the “Gohl as Serial Killer” story has a simplistic appeal to it, and it fits with murder stories being peddled by most true crime writers and TV producers.

Admittedly, I’m not much of a self-promoter or salesperson—hell, if I was I could probably become a university administrator and finally pay off some of my debt. One small success, though, came when a couple of Grays Harbor residents, one a musician and the other an archivist, wrote to tell me that they were writing a musical play about Billy Gohl, and after reading The Port of Missing Men, they were changing the focus toward class struggle, and Gohl as a militant labor unionist. Hopefully there will be other small victories like that.

The UW Press has been great at getting the word out about the book and about the real Billy Gohl, but this is going to be a long struggle. My hope is that the more I write and speak about Grays Harbor employers—and their counterparts throughout the Pacific Northwest—the more that people will come to realize that employers were willing to use any means necessary to maintain workplace and community control—and keep business churning without inconvenient disputes led by people like Gohl. A big step in that direction will come when I finish my big book on class, community, and conflict in Grays Harbor, between 1900 and 1940 – the one based on my Ph.D. dissertation.

On the other hand, especially after the uprisings against racism and oppression in 2020, it seems as if more people are willing to accept the reality of an oppressive criminal justice system that doles out punishments based on race, class, citizenship, income, and other factors. It’s also increasingly easy to see the corporate bias of the press—the spectacle of the Bezos-owned Washington Post peddling its version of the union movement growing at Amazon is perhaps the most obvious. The Port of Missing Men strikes deep at the heart of the business-friendly media. Hopefully the book convinces others to take a critical look at the anti-labor bias within media coverage of Billy Gohl and the wider labor movement in the Pacific Northwest—and beyond.