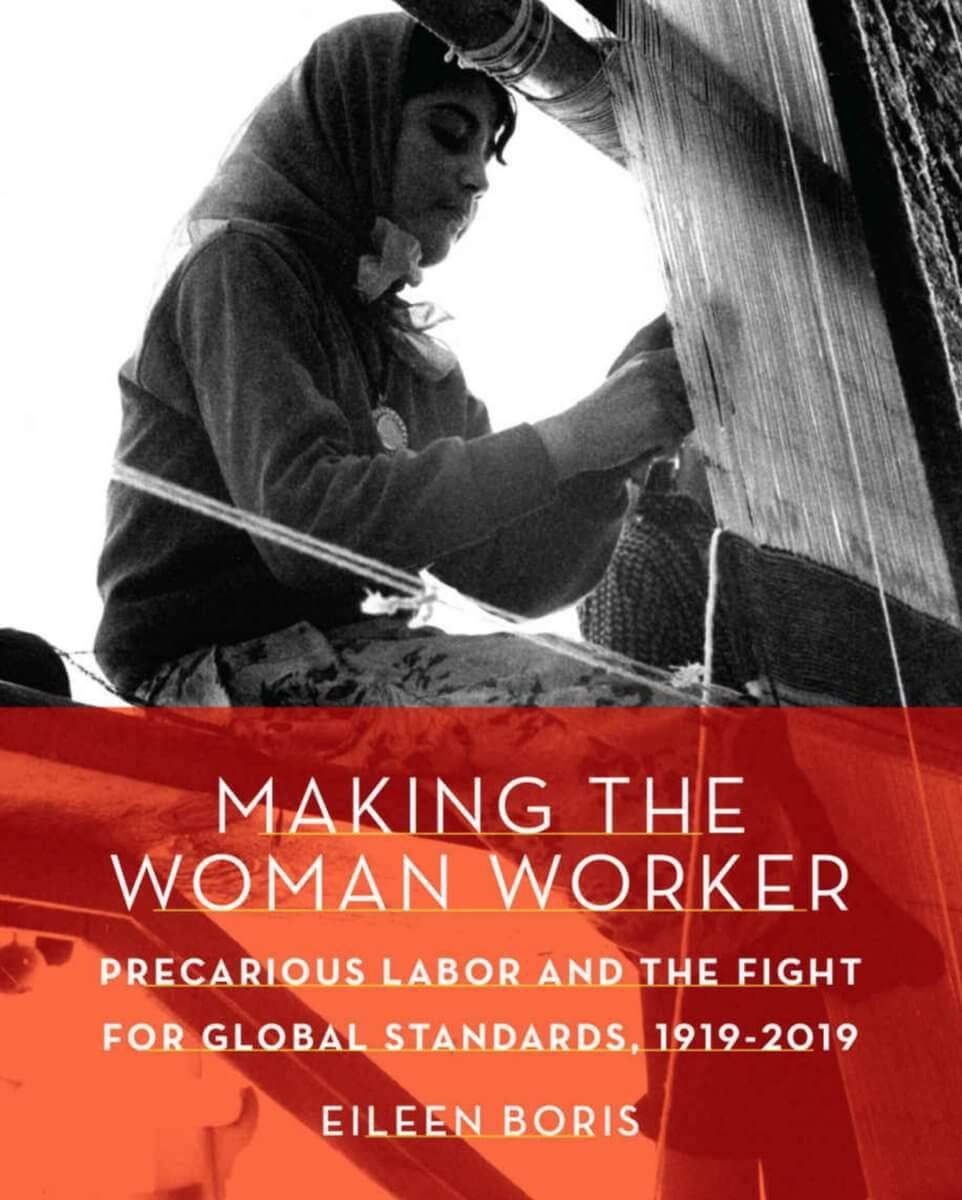

As we celebrate International Women’s Day, we are pleased to host a roundtable discussion on Eileen Boris’ new book, Making the Woman Worker: Precarious Labor and the Fight for Global Standards, 1919-2019. Boris’ book, centered on the International Labor Organization, the global United Nations agency that sets labor standards, offers a window to understanding gendered labor systems and the struggles to redefine them through the ILO. The four roundtable commentators focus on key themes in Boris’ book.

We will post a new contribution to the roundtable each day for most of the week. We start today with an introduction from Emily E. LB. Twarog, who organized the roundtable, and the first contribution, from Katherine Turk (below). Come back Monday for “From Othering to Inclusion,” by Naomi R. Williams. On Tuesday comes Chaumtoli Huq’s contribution, “Realizing the Global Labor Rights of Domestic and Rural Women Workers: Fight for Global Standards Must Continue at the Grassroots Level.” On Wednesday, we will publish “Building Bridges from Shared Experiences: Learning from Maria Mies and India’s Lace Makers’ Study,” by Sarah Lyons. Finally, on Thursday we bring author Eileen Boris’s response. We hope hope you’ll come back each day for each installment. (The links above will start to work each day as the posts come online.)

Introduction

Eileen Boris’ new book is an important reminder of how social construction and capitalism have for so long defined women’s public and private lives. We are faced with a daily barrage of reminders that women have been and continue to be “other” in society.

When I was asked to put this roundtable together, I knew I wanted to bring in a variety of voices to chime in on Boris’ critical work, Making the Woman Worker. I wanted to gather the views of historians but also those who are working as organizers. I was thrilled that each of the commentators

- Chaumtoli Huq, who I only recently met at the 2019 LAWCHA conference in North Carolina and am excited to work with more;

- Katherine Turk and Naomi Williams, who I have known for some time and respect immensely for their research and perspectives; and

- Sarah Lyons, who I know through my work with the Hands Off, Pants On campaign in Chicago where I live.

accepted my invitation to this roundtable as I think their responses all bring unique and important perspectives. I wrote that “I chose each of you because of your distinctive voice and your research areas. I have no doubt that all of you will read this book and have something very different to say about it. I am hesitant to give you guiding discussion questions because I think whatever your most powerful or immediate reaction is to the book, or a section of the book, should be what you write about.” I also asked them to engage with the book based on their current research, teaching, and/or activism. Their pieces each exceeded my expectations, and I think you will find many rich insights as you read.

Emily E. LB. Twarog, Associate Professor

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Women’s Labor History and the Transnational Turn

Katherine Turk, Associate Professor of History

University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Making the Woman Worker is a master class in gender history: relational, intersectional, and attentive to how power works. As Boris shows, placing women at the center of the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) story offers the key to understanding sweeping developments in the past century of global labor. The ILO’s shifting approach to women created the woman worker as both a subject and a symbol. She was always an “other,” uneasily incorporated into the ILO’s campaigns or excluded outright, and women from the global South were doubly disadvantaged as “difference’s other.” The hallmarks of her labor, as defined and reified by the ILO, have crept across the workforce. In the end, “the woman worker has turned into a harbinger for a world of feminized labor—part-time, short-term, and low-waged—in which there are no employers but only the self-employed, able to labor as long as they can for as little as possible.” (1)

Boris is a titan in the fields of gender and labor studies, and with this book, she firmly joins the many American historians who have made the transnational turn.[1] Their works have illuminated new dimensions of politics, intellectual currents, and social movements by placing the United States in global perspective. But anything can be transnational-ized by widening the lens. What specific insights does this approach bring to the history of laboring women in America? Making the Woman Worker reveals several.

First, the book’s transnational perspective helps us better understand the history of American working women. The major turning points in that history may have seemed unique to industrial democracy in the United States, but they were in fact moments of global debate and transition: the rise of sex-specific labor standards; the tension between gendered protections and equal rights; the triumph of a deeply flawed de jure equality paradigm; and, most recently, policymakers’ embrace of an allegedly neutral market that deepens inequalities of race, class and gender even as it creates precarity and poverty for increasing segments of society.

Striking a blow at American exceptionalism, Making the Woman Worker demonstrates that American reformers, activists and workers could be far from the forefront of understanding or addressing the problems they faced at home. At points, women from other parts of the world helped American women acknowledge their own biases. U.S. labor feminist Frieda Miller believed that Western women dressed better for work. “If you lived your whole life in a sort of tent with slits in it,” she once asked, “how do you think you would feel?”(97) On a trip across Asia in the mid-1950s, Miller met women who taught her that their choices about work and dress were no less legitimate than Western women’s, whose fashions seemed to increase the odds that their wearer would be objectified. Decades later, the ILO fully endorsed domestic workers’ rights, a major paradigm shift relating to a persistent and growing concern in the United States. But grassroots social movements in Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean deserve most of the credit for fomenting this change.

Relatedly, Boris recovers how American labor feminists were themselves thinking globally, whether they were visionary in their expansive perspectives or plagued by “civilizationist” (21) blind spots. Miller served as the Director of the U.S. Women’s Bureau from 1944 to 1953 and advised the ILO on women’s workplace issues. Her collaborator, economist Mildred Fairchild, headed the ILO’s Women’s and Young Workers Division in those years. The pair developed a set of programs on women’s rights for the ILO that included regulating and abolishing industrial home work, drawing domestic workers into labor standards coverage, strengthening maternity leave provisions, and more. In the early 1960s, U.S. Women’s Bureau director Esther Peterson urged the ILO to adopt an expansive program on women’s employment to benefit women in all kinds of economies. But she revealed a Western belief in development’s virtues and inevitability, claiming that industrialized nations could share lessons from their history so that “women, as a country develops, will not be used as a source of cheap labour.” (89) Boris’ transnational perspective recovers the complexity and fullness of labor feminists’ approaches where as a solely US-based study would truncate them.

As is evident from even the best-intentioned American labor feminists, global solutions for laboring women are harder to create than domestic ones, not least because such campaigns must bridge vast social and geographical distances. For most of its history, the ILO and its approach were remarkably narrow. Participation was limited to those with the means to travel to conventions, the time to devote to the cause, the right stature within their countries, and the language skills to take part. As a result, Western women often “supported a universality that matched their lives, speaking for all women and pushing for general rights by defending the most oppressed.” The ILO itself “judged success by whether forced or bonded labor had evolved” to resemble “the achievements of the Western male worker.” (21) The form of equality some Western feminists advocated fell far short of what could help the women they meant to champion. As Boris asks, “Could equal treatment of men and women within a nation be enough in a world where some places remained dependencies of colonial powers that benefited from the fruits of empire?” (85) Certainly not.

But Making the Woman Worker reveals that global responses to the problems of exploitation and inequality are possible and necessary, as workers, capital and information flow across national borders with increasing ease. An organization like the ILO has a key role to play, its flawed history notwithstanding, and it has attempted to meet the challenge. For example, as the ILO began to sharpen its focus on migrant labor and the informal sector in the 1990s, domestic workers and their concerns moved to the center. Workers and employers “had different laundry lists,” (211) but the ILO helped generate an “inquiry into worldwide conditions for domestic work” (214) that placed workers and their representatives in dialogue with trade unionists and policymakers. And while few nations have ratified the ILO’s Home Work Convention, now twenty years old, its passage reveals “the kind of transnational networking and coordinated strategy necessary for success.” (188) Such victories within the ILO offer a foundation for activists and policymakers as they keep pushing.

By decentering the United States, Making the Woman Worker shifts the timeline of U.S. labor history and ends on a relatively optimistic note. The book’s most basic arc is familiar. In the 1970s, Fordism buckled under the weight of neoliberalism, weakening traditional labor unions and the male breadwinner norm. Precarity spread across the labor force, ruining more meaningful attempts to create social rights and raise workplace standards in the face of “unmitigated corporate power.” (241) But Boris recasts the past 25 years, to which she dedicates the last third of the book, not as a downward spiral, but as an era when the ILO expanded its conceptions of work and built power in promising new ways.

In particular, the 1996 Home Work Convention reshaped the ILO into an advocate for workers it had previously excluded. It made the woman who “took in garments to sew, crackers to pack, electronics to assemble, or papers to type” (157) into a worker deserving of rights and protections. Finally, the organization of work, not its site, was what mattered. Care work, whether remunerative or not, also attracted more of the ILO’s attention and respect. Yes, “[r]eproductive labor won recognition as work at a time when standardized employment had become badly frayed,” (198) but “the commodification of care is already upon us, and the issue is whether care workers will reap the rewards of their labor.” (242) The ILO’s new focus benefitted the organization itself, refreshing its relevance in challenging times.

Making the Woman Worker offers wisdom for activists and scholars alike. From the beginning the ILO was supposed to represent all workers regardless of sex, but few women were in the jobs it sought to protect or regulate. Today, even fewer workers can claim good jobs, but women are on the ILO’s agenda like never before. The ILO itself has been limited from its inception. Its processes take a long time, and even participating nations can treat its conventions like recommendations. But advocates should not throw out the baby with the bathwater, and Boris explains how the ILO can continue to adapt to the challenges of the 21st century.

The book also serves up insights for scholars, revealing the benefits of a wider perspective. The borders of the nation are porous and flexible, especially where work is concerned. The United States has always been embedded in global networks, markets and communities. American gender norms have never developed in a domestic vacuum. Historians must continue to account for these facts, and Boris shows us how.

Check back tomorrow for Naomi R. Williams’s contribution, “From Othering to Inclusion.”