When Notre Dame Cathedral caught fire in Paris on April 15, 400 firefighters were deployed to tackle the blaze. One of those workers was seriously injured, and two police officers were also hurt. Emergency workers risked their lives to remove artefacts from the burning cathedral, but most reports emphasized the value of the artefacts and artworks rather than the people who saved them. Media coverage of the global reaction to the fire focused on the great sadness many people feel at the potential loss of an iconic building. Catholics have understandably been particularly upset at the loss of the church. In France, the president, Emmanuel Macron, has promised that the Cathedral will be rebuilt, and two French billionaires have pledged millions of dollars towards the repairs. Experts have explainedhow technology can assist in the reconstruction of the destroyed parts of the building and there has been much commentary on the cultural significance of the cathedral.

As this was all unfolding, I kept thinking about Bertolt Brecht’s 1935 ‘Questions from a Worker Who Reads’. In the poem, the worker asks questions about the people who are missing from stories about famous monuments and historical events – the labourers who ‘haul(ed) up the lumps of rock’; cooks who prepared the feasts for kings; the masses of workers who built, fought, and died for all these important historical figures.

And this is what kept coming back: who built Notre Dame? How many of those workers were injured or died during the construction? Who has been maintaining the cathedral – fixing lights, unblocking toilets, keeping it neat and tidy, answering the phones, serving in the gift shop? What will happen to these workers while the building still smoulders? No doubt, an army of tradespeople will be employed in the rebuilding: will they be paid decent wages and will they be safe at work?

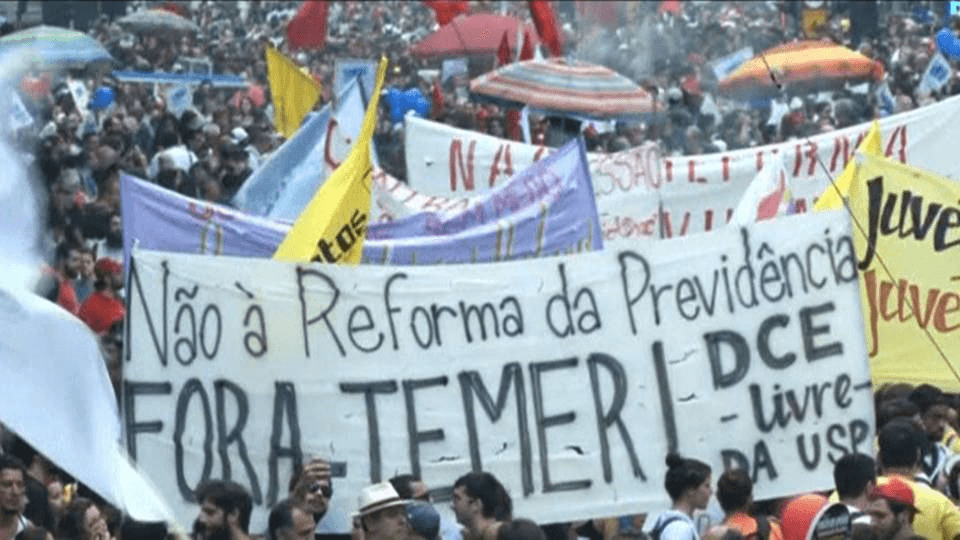

Questions lead to more questions, such as how the reporting on the Notre Dame fire reflects cultural biases based on class and race. Responses to the fire show how certain buildings or places can be attributed more value than others. Some have compared responses to Notre Dame with reactions to the June 2017 fire at Grenfell Tower, which housed working class low-income people, where 72 people lost their lives. The fight for affected families to be rehoused and for dangerous flammable cladding to be removed from other social housing blocks continues, but have working-class residents of social housing been treated as less important than artefacts in a famous cathedral?

Destruction of other significant religious or cultural buildings around the world have not received the same attention as Notre Dame, such as the loss of Black churches in Louisiana in April to arson by a white supremacist. While the churches might not be as old as Notre Dame, they are extremely important to the local community, and their destruction as the result of a hate crime is deeply significant. Was there less of an outcry because the affected community are people of colour? The Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem also experienced an accidental fire on the same day at Notre Dame, but the fire was not reported on by Western media despite the religious significance of this site, which points to the devaluing of sites outside of the west, as well as the ongoing suspicion of anything Muslim.

For many, Notre Dame is an iconic symbol of the Catholic Church, but for others, it is a symbol of French colonial and imperial power. The outpouring of grief for the lost building has been seen as symptomatic of the lack of concern for the rights of people under colonial rule and the continued impact of French colonialism in terms of racism and discrimination faced by African and Muslim immigrants in France today. Meanwhile, some right-wing outlets were very quick to try attribute blame to Islamic terrorists.

Responses to the Notre Dame fire often emphasize the Cathedral’s age, but in Australia, people seemed less bothered by the potential loss of sacred trees that are just as old. Indigenous activists in Victoria have been fighting to protect 800-year-old sacred trees, including a birthing tree where countless generations of Djap Wurrung people have been born, from a highway expansion. Indigenous people in Australia have experienced many such fights, as their land and sacred sites have been destroyed to make way for roads, mines, and building developments. Some public figures here have suggested that Australia should assist with the cost of rebuilding Notre Dame – an idea that seems particularly galling in the light of Indigenous disadvantage and the continuing gaps in life expectancy and educational outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Wider suggestions that the cathedral ‘belongs’ to the world (and therefore the world should contribute to the repair fund) insult the millions suffering under austerity measures or experiencing racism due to the rise of right-wing rhetoric (particularly when this hateful rhetoric has a religious basis), or living without adequate housing, nutrition, education, or health care around the world.

I visited Paris as a working-class teenager in the 1980s (after saving for months) and I remember going in to Notre Dame cathedral and admiring the skill of the workers who created the stained-glass windows, the beautiful stone work, the intricate wood carvings. To see the fruits of their labour destroyed is a great shame. But what is the chance that the focus of any rebuilding will be on the workers? More likely, we will hear stories about the value of the artefacts, the use of technology to recreate lost sections, the importance of the building to French history, and the willingness of the powers-that-be to make sure everything is restored.

As we listen to those stories, we should remember that reports on historical places and events are always classed and raced. As Brecht’s worker says at the end of the poem, ‘So many reports/ So many questions’.