In 1886, several prominent European socialists came through Cincinnati in search of insights into America. Their local comrades–“delightful German-American friends” took them to a local dime museum. There, a showman introduced cowboys with “stereotyped speeches about them,” as his subjects lounged about “in their picturesque garb, and looking terribly bored.” Then, one of the cowboys, “singularly handsome face and figure, with the frankest of blue eyes, rose and spoke a piece. To our great astonishment he plunged at once into a denunciation of capitalists in general and of the ranch-owners in particular.” He had asked the Eastern papers to “do what the Western ones were afraid or unwilling to do, and state clearly the case of the cowboys, their complaints and their demands.” The European reds had met John Harrington Sullivan, a red-blooded American cowboy known as Broncho John with a red perspective drawn from his personal experience in the West. (Aveling, 156-157)

The speaker had already lived a colorful life. He seems to have been born in 1859, though it’s not certain. It is possible, but unlikely, that he had been born in Wyoming, as later claimed. He grew up “in the companionship of wild creatures. I loved wild animals.” He “began life among men at about six years of age,” going to work “among the uncivilized, the wildest and most severest of man, beast and climate; also among the greatest of good men, such as explorers, army officers, missionaries, great Indian chiefs and nature’s beauties,” Sullivan’s critique of the dominant civilization began early, when he came to have “great sympathy for the outlawed pony, especially when he was made so by cruel masters,” and, by the age of eight, they began to call him “Broncho John.” (Par. 2)

Sullivan took off on his own at the age of twelve, around 1871, “I started out alone, with the exception of two first-class Oregon horses.” When some prospectors threatened to take them, he demonstrated his shooting skills to provide “a good feast of prairie chickens.“ One of them asked him directly if he would fight “and I told him to try me once.” Continuing south he passed through “many little Mexican settlements,” where he fell in “with the Mexican and half-breed boys. I liked them all because they were kind and honest.” In New Mexico, he joined several old cowboys on their way to San Antonio. From there, Sullivan joined a cattle drive that consisted of “eight Northern white cow boys and six Mexicans, all long haired men and a boy, ‘myself.” They were later joined by an Indian known as Prairie Fox, whose tribe was unspecified though his name hints he was one of the northern tribes trying to make his way back home.(Sullivan)

Apprenticeships were short in that time and place. Stalked by gangs of rustlers and unidentified Indian war parties, they assigned the boy to learn scouting from Prairie Fox. At one point a Commanche war party wounded and cornered Prairie Fox, but Sullivan used his better firepower to break the encirclement and “managed to get the wounded scout to camp,” where he later died. At thirteen, Sullivan, at thirteen, became “a full fledged scout and guide.” From that point on, he piloted them past bands of white rustlers, Pawnee and Sioux: “They did no damage and I don’t think we did either.” (Sullivan)

These skills placed Sullivan in greater demand than an ordinary cowpoke. Wagon trains, freight services, and stagecoach lines all needed scouts, as did the U.S. Cavalry. He also attained considerable fame for his talents with a rope and a six-shooter. In the sparsely populated region, an active traveler, such as he, may well have met all the people Sullivan claimed to have encountered– Kit Carson, “Wild Bill” Hickok, “Buffalo Bill” Cody, and “Texas Jack” Vermillion of Wyatt Earp’s vendetta riders after Tombstone. He also mentioned Major Frank North of the Pawnee Scouts and Generals George R. Crook, as well as George Armstrong Custer. In New Mexico, Sullivan met Frederick Remington who used him in a painting on which statue of “The Cowboy” in Philadelphia. (Sullivan)

By the end this tumultuous and violent decade, real change settled over the West. The first wave of permanent small farmers and ranchers faced a severe crisis. In 1862, the Homestead Act permitted landless persons to occupy parts of the unclaimed public lands and gain ownership should they develop it. Vast numbers began turning up after the Civil War. However, a system aimed at establishing small farms worked poorly in areas suited to mining or cattle or sheep-raising. Many of these claims required going into debt and the banks confronted the Panic of 1873 by passing along their problems to the homesteaders.

As far as cowboys were concerned, the growth of the railroads ended the need for overland freighters, stages, and wagon trains, as well as those long cattle drives. Development destroyed the massive buffalo herds and the Indians living beyond control of the government. Times, recalled Sullivan, had made it “increasingly difficult for the long-haired saddlemen, teamsters, and riflemen to make a living “ (Memories, 8)

Through the rest of the decade, the usual rule of capitalist development followed, as the larger landowners gobbled up the smaller ones, particularly in the cattle business. An open-range system of grazing had dominated the Great Plains, but now the larger enterprises increasingly dominated those lands and introduced barbed wire and fencing to create a more closed system to the detriment of the smaller holdings.

Sullivan reflected that original settlers of the West “turned their entire property over to people they never saw before, but knew they were the genuine native whites. The speculators gave orders to have their great herds at certain points in two or three years, giving dates. The speculators went back east and never heard nor saw anything of the men or animals until the dates and places appointed two or three years previous.” (Sullivan)

Even as America imposed horrific realities upon the cowboys, it began the process of scrubbing up and romanticizing their image. Having warred repeatedly against its Spanish-speaking neighbors to the south and west, it became easy to forget that “cowboy” merely anglicized the “vaquero,” the Spanish job imported to the New World. The movement of vast numbers of slaves to the arid lands of Texas at the onset of the Civil War brought made for a considerable African-American presence that even outlasted the arrival of Jim Crow laws. Females also performed the work and their status in the overwhelmingly male settlements accorded them greater rights in the West, Wyoming according them the right to vote as early as 1869. The dime novels and the silent screen would remake the cowboy into something that looked rather consistently more Randolph Scott or John Wayne.

The actual future for all of them took a very bleak turn. When Broncho John set out on his career, the trail hand could have ridden the hundreds of miles of the cattle drive alongside the owner of the cattle and plan his own future as a landowner. In what seemed like the blink of an eye, he found himself increasingly tied to a more permanent working life, bunked in with others on an isolated ranch to work directly under the thumb of a exploited and hopeless work force of cowboys .

Sullivan found work as an army scout through 1881 and 1882, though “Buffalo Bill tried to recruit him for his touring show. The following year, Cody planned his more elaborate “Wild West Show” and conditions had reached the point where Broncho John accepted the offer to become part of the first troupe. They found such a demand for this that one of Cody’s partners, William F. Carver–“Doc” Carver–started a new company in 1884, recruiting Sullivan as his right-hand man.(Memories, 8)

The end of the summer, though, brought legal difficulties for Carver that imploded the entire company. Sullivan, forty Indians, a dozen horses, two antelope, a deer and a bear found themselves arrived in Valparaiso, followed by Carver with a dozen cowboys, a “16-piece Negro band,” and others. Then the lawyers of the creditors descended on the group. Broncho John and others immediately appealed to the local residents who organized a relief committee that kept the Indians together. Sullivan arranged to Chicago, after which the Bureau of Indian Affairs would get them home. Before they left, though, they gave a performance in gratitude to the local people. (Memories, 8 and The Stroller)

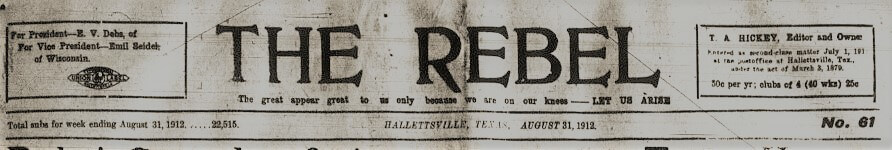

Out of this came Broncho John’s old Wild West show, which generally toured in the Midwest, but its movements can be easily traced through the recently digitized collections of contemporary newspapers. In this capacity, he came to the dime museum in Cincinnati and encountered Eleanor Marx Aveling, her husband and German socialist Wilhelm Liebknecht who had defied his government in opposing the Franco-Prussian War.

Eleanor’s father, Karl Marx had had spent his life formulating a coherent social and economic critique of capitalism based on what he saw and studied in the Old World. Already, though, the U.S. had claimed to be taking an exceptional course, and the skeptical Marx had always wanted a closer look, but never got the chance. A striking woman, Eleanor–also called Jenny or Tussey–had become an important movement figure in her own right. Interested in the Irish cause by the age of twelve, she began accompanying her father to labor and socialist conferences at sixteen. After the death of her parents and a sister, she took on even more public roles. In 1884, she joined the dry-as-dust Social Democratic Federation and helped William Morris and others launch a new Socialist League, which looked to mass work. She also helped launch the Women’s Trade Union League and helped to lay the foundations for what would erupt as the Great Dock Strike of 1889. Her long interest in literary, artistic and theatrical work not only explains much about her association with Morris but her interest in the Wild West theatrics in the U.S. She certainly would have rightly seen what Broncho John told her and her companions as a great vindication of her father’s perspectives.

Sullivan spoke from the heart about the plight of the cowboy. He explained the impossibility for cowboys to find work during off-season, which forced them to try to support themselves and their families on as little as the $120 to $150 they could earn in a year. “Experience has taught them that to ask for an increase in wages means immediate discharge from the service,” he explained, adding that the owners’ association would then circulate his name. This entailed not only blacklisting the cowboy as a possible employee but a refusal to do business with them, should they attempt to run some cattle on their own. (Aveling, 162) Indeed, the hired guns of the big ranchers regularly regarded the blacklisted cowboy as a rustler or potential rustler, and treated them accordingly.

These practices meant that the cowboys had no organization while their employers have “one of the strongest and most systematic and, at the same time, despotic unions that was ever formed to awe and dictate to labour.” Because their work left cowboys dispersed in small bands over miles upon miles, concerted action seemed “almost out of the question.” Still, so many had “awakened to the necessity of having a league of their own” that Sullivan thought a Cowboy Union or an Assembly of the Knights of Labor seemed likely. They also hoped for the success of Henry George and the various labor party movements than underway in various American cities. (Aveling, 158-159)

In fact, some members of Broncho John’s Cincinnati troupe may have been blacklisted refugees of one of the several cowboy strikes over the previous years. Early in 1883, twenty-four cowboys from the three ranches issued an ultimatum against several corporate-owned operations demanding better wages and setting March 31 as a strike date. Cowboys on five ranches joined, involving several hundred hands. The strikers held out for ten weeks, though the bosses prevailed. Although more sparsely documented, several other strikes took place by 1886. (Allen; Dearmont)

Finally, law enforcement remained entirely in the hands of the ranchers, who arranged to pass measures that only benefited themselves, such as the Maverick Law in Wyoming. Backed by the law, the road agents actively pushed the small homesteader and rancher from the area. The courts and the press remained under what Sullivan called “the terrorist regime of the ranchers.” Over time, “small setters, robbed of their little stock, become cowboys and the wage-slaves of the ranchers, who are all staunch upholders of the sacred rights of property.”(Aveling, 163-165)

Hollywood and the TV studios never had much interest in the social realities of the West. They present big ranchers, small ranchers in the process of becoming big ranchers, and oilmen as cowboys. Usually, the landless cowboy rides across the silver screen as an independently wealthy tourist with apparently magical saddlebags that provide limitless food and funds.

The recollection of Broncho John is that of a different kind of western hero. One that understood how only union and collective action would secure the cowboy’s independence. Only the violent repression those real cowboys permitted Hollywood to work its magic, but it should not prevail over the long run. In the big picture, Sullivan’s story also reminds us of the folly of most arguments about American exceptionalism. Sure, every civilization–and every part of a civilization–has unique and peculiar features, but they also share some very common experiences. The greed and ruthlessness of the big owners, the transformation of the free-spirited cowboy into a wage slave, and the class nature of the American West made it part and parcel of the rest of the industrial and industrializing world.

When the real cowboys met the comrades, they shared a common perspective on the global order to which they aspired.

Sources: In order of first use:

Aveling: Edward Bibbins and Eleanor Marx Aveling, The Working-Class Movement in America (2nd ed.; London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1891), 156-57. See also: Leslie Derfler, “The American Cowboy: Note on a Marxist Perspective,” Journal of the West, 38 (July 1999), 72-76.

Paragraph 2: He donned the sombrero and spurs when he was 12 years old,” and “fifteen years that have passed since then.” “Cowboys on the Alert,” The Sun, February 21, 1886, p. 3. There was also a “Broncho John” Sullivan with a ranch in Wyoming later.;

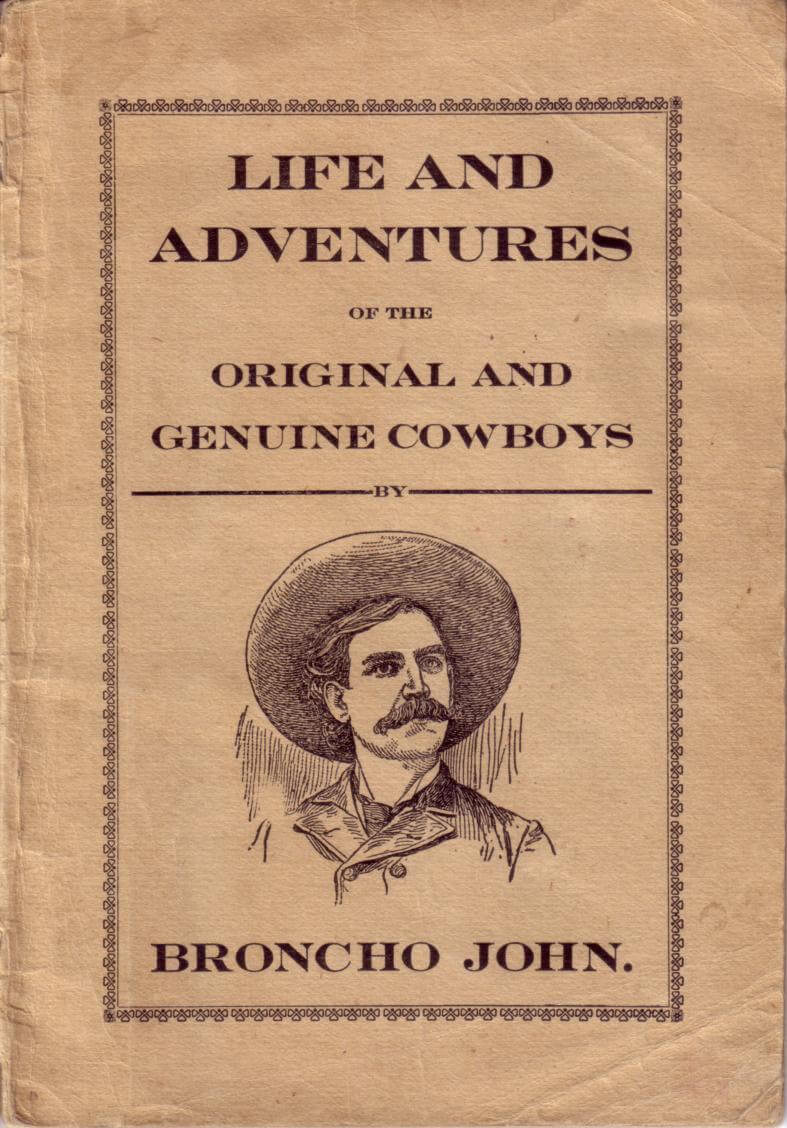

Sullivan: Sullivan autobiography: The transcription is taken directly from a book written by Broncho John H. Sullivan in 1896 titled Life and Adventures of Broncho John: His First Trip Up the Trail. The book has been transcribed exactly as it was written. Transcribed by Steven R. Shook http://www.inportercounty.org/Data/Misc/broncho-john-book.html. Source Citation: Sullivan, J. H. 1896. Life and Adventures of Broncho John: His First Trip Up the Trail. Valparaiso, Indiana: J. H. Sullivan. 24 p. Copyrighted 1896-1900-1903-1905-1908. byJ. H. Sullivan. Copyright © 1996-2008, Cheryl Trowbridge-Miller. Copyright © 2008-present, Steven R. Shook. All Rights Reserved.

Memories: “‘Broncho John’ Sullivan’s Memories of Half a Century. As Told To, and Recorded By, His Son, John H. (‘Texas Jack’) Sullivan,” Valparaiso, Indiana Vidette-Messenger, July 9, 1935, p. 8. http://www.inportercounty.org/Data/Misc/broncho-john-VM-1935.html Also: Vidette Messenger, September 27, 1951 p. 2.

The Stroller, “40 Destitute Indians Stranded In Valparaiso,” Vidette Messenger, June 14, 1962 p. 1 & 7 deposited at http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=28790774

Ruth Alice Allen: Chapters in the History of Organized Labor in Texas (Austin: University of Texas Publication 4143, Austin, 1941);

Dearment: Robert K. Dearment, Deadly Dozen: Twelve Forgotten Gunfighters of the Old West. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003).

2 Comments

Comments are closed.