This is the third post that introduces the important themes and issues highlighted in the new edited collection Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education. -ed

When Claire Goldstene and Eric Fure-Slocum asked me to contribute a chapter for their proposed book examining precarious faculty labor in higher education, I was both honored and nervous. It was the latter half of 2019, and my work in academic labor advocacy had waned over the previous few years due to extensive family obligations and the urgent need, familiar to most contingent faculty, to seek stable, better-paying employment. But my nervousness was probably also attributable to the fact that I was somewhat burned out by the intensity of the decade of activism into which I had thrown myself, with Joplinesque ferocity, in 2009 when we launched New Faculty Majority.

When Claire Goldstene and Eric Fure-Slocum asked me to contribute a chapter for their proposed book examining precarious faculty labor in higher education, I was both honored and nervous. It was the latter half of 2019, and my work in academic labor advocacy had waned over the previous few years due to extensive family obligations and the urgent need, familiar to most contingent faculty, to seek stable, better-paying employment. But my nervousness was probably also attributable to the fact that I was somewhat burned out by the intensity of the decade of activism into which I had thrown myself, with Joplinesque ferocity, in 2009 when we launched New Faculty Majority.

When Claire Goldstene and Eric Fure-Slocum asked me to contribute a chapter for their proposed book examining precarious faculty labor in higher education, I was both honored and nervous. It was the latter half of 2019, and my work in academic labor advocacy had waned over the previous few years due to extensive family obligations and the urgent need, familiar to most contingent faculty, to seek stable, better-paying employment. But my nervousness was probably also attributable to the fact that I was somewhat burned out by the intensity of the decade of activism into which I had thrown myself, with Joplinesque ferocity, in 2009 when we launched New Faculty Majority.

During that decade I had met inspiring new colleagues and made lifelong friends whose collaboration and solidarity were a professional and personal lifeline in the midst of the muck and the mire (how apt is Claire Raymond’s chapter!) of contingent academic employment. Camaraderie and cooperation saw us through internal and external conflict and allowed us to make small but important practical gains, with sometimes outsized psychological and political impact. But we also had losses, the most difficult of which were the deaths of four treasured colleagues, Steve Street, David Wilder, Miranda Merklein, and April Freely.

David, with whom I taught at Cuyahoga Community College in Cleveland, had become a dear friend. He and I had many conversations about labor history and strategy (he the expert in both), academic culture, the academic labor movement, how to teach effectively. We shared family and health news, talked politics, and agonized over the lack of healthcare and retirement options that regularly upended both of our lives, often trying to think of how to address the direct interconnections between contingency and so many of these types of challenges.

David died in 2017, lost to the plague of gun violence, just weeks before he was due to be hired full-time with benefits for the first time in his academic career, and after a lifetime of labor activism, artistic excellence, and pedagogical impact.

Throughout my decade of activism and teaching, I had tried, inspired by people like David, to learn and write and organize as hard as I had taught and fought, but the cycle of life, and the lifecycle of activism, eventually caught up to me. I took a much-needed step away.

Thinking about my lost, brilliant colleagues, about their determination, commitment, and confidence in the power of collective action, helped me overcome my hesitancy to contribute to this book. So did Claire’s and Eric’s list of contributors and topics, which features an invaluable range of experience, historical perspectives, and energizing forward-thinking. Finally, their request that I focus on students really drew me in. The ramifications for students, for education, for democracy, and for labor activism, as well as the labor history of the “gig academy” and efforts to combat it, are all themes that have always been paramount to me as a professional, as a parent, and as a citizen.

David and I often talked about the challenge of teaching in the context of contingency, and how important it was for the sake of the students. He taught Art; I taught English composition, but it wasn’t that we thought we could teach more effectively than anyone else how to draw, paint, read, write, think about art and language. What we often observed and discussed was that our precarity was itself also instruction, part of our students’ education into how the world is constructed, and that our response to that precarity was also instructive.

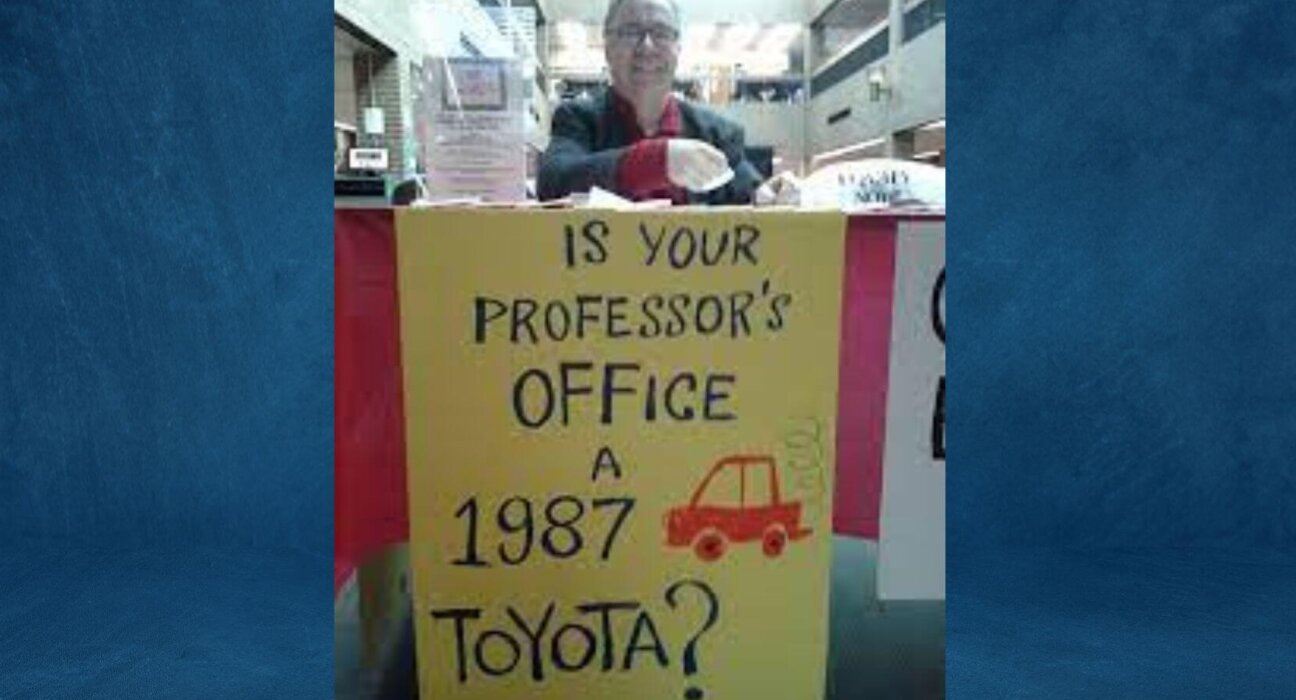

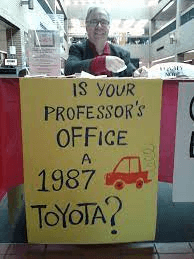

We agreed that it was impossible for our students to learn from us without also learning about the context in which they were learning from us. We pondered whether it was happening organically – if the campus, as Rich Moser put it, really is the best classroom. An activated campus, we discovered, is an excellent classroom. After students saw David staffing an information table during Campus Equity Week for which he had provided the pointed posterboard illustration, many of them let us know that they came from union families or were in unions themselves and asked why didn’t we just unionize already – they would support us if we did.

Our activism provides us with an incredible opportunity for reciprocal learning about, for solidarity with, and for action toward an expansive notion of the common good. This is what I tried to convey in my chapter, “Common Ground for the Common Good: What We Mean When We Say ‘Faculty Working Conditions are Student Learning Conditions.’” In it, I reflect on our movement’s foundational principle and battle cry. I once wrote about how, when I and some of my colleagues started our activism, this principle seemed so obvious and so self-evident to us as faculty that we didn’t realize we actually had to think about it, teach it, and to learn more about it so that we could communicate it more effectively to help spur and support organizing and action.

For me, this dialectical process of learning, communicating, and acting was hugely influenced by conversations with colleagues and long-time labor activists and historians like David, and like the colleagues in and outside this book. The book is a conversation, spurring more conversation – and action. I think the endurance of efforts like Bargaining for the Common Good and the emergence of expansive, solidarity-focused organizations like Higher Education Labor United (HELU) and United Campus Workers (UCW) are the most hopeful and exciting developments in higher education-related labor activism in years, and as an academic staffer I am eager to re-enter the fray with new experiences and insights to add to my history as a faculty activist. But I also recognize that we would not have gotten to this point without the more focused work of not only the contingent faculty movement, but of social justice equity campaigns like Black Lives Matter, March for Our Lives, #MeToo, and others that highlight specific issues and challenges, which higher education, as a locus and an agent of the common good, is charged with examining, addressing, and integrating.

For me, being a contingent faculty activist was an incredible portal to the larger world of labor history and activism. I learned about my personal connections to that history, and I try to integrate those lessons into the personal and professional choices I make from now on. For those of us who did not have backgrounds as labor historians or activists when we began this work, that education has been one of the gifts of the work and of books like this one.

Excerpts of 2014 IHE interview with Miranda Merklein

Maria taught as a contingent faculty member for over fifteen years in Maryland and Ohio and has published and spoken widely on the topic of contingent faculty equity, organizing, and coalition building. In 2009, she co-founded New Faculty Majority: The National Coalition for Adjunct and Contingent Equity, a 501(c)6 membership and advocacy organization, and served as its president. She has undergraduate and graduate degrees from Georgetown University in Washington, DC