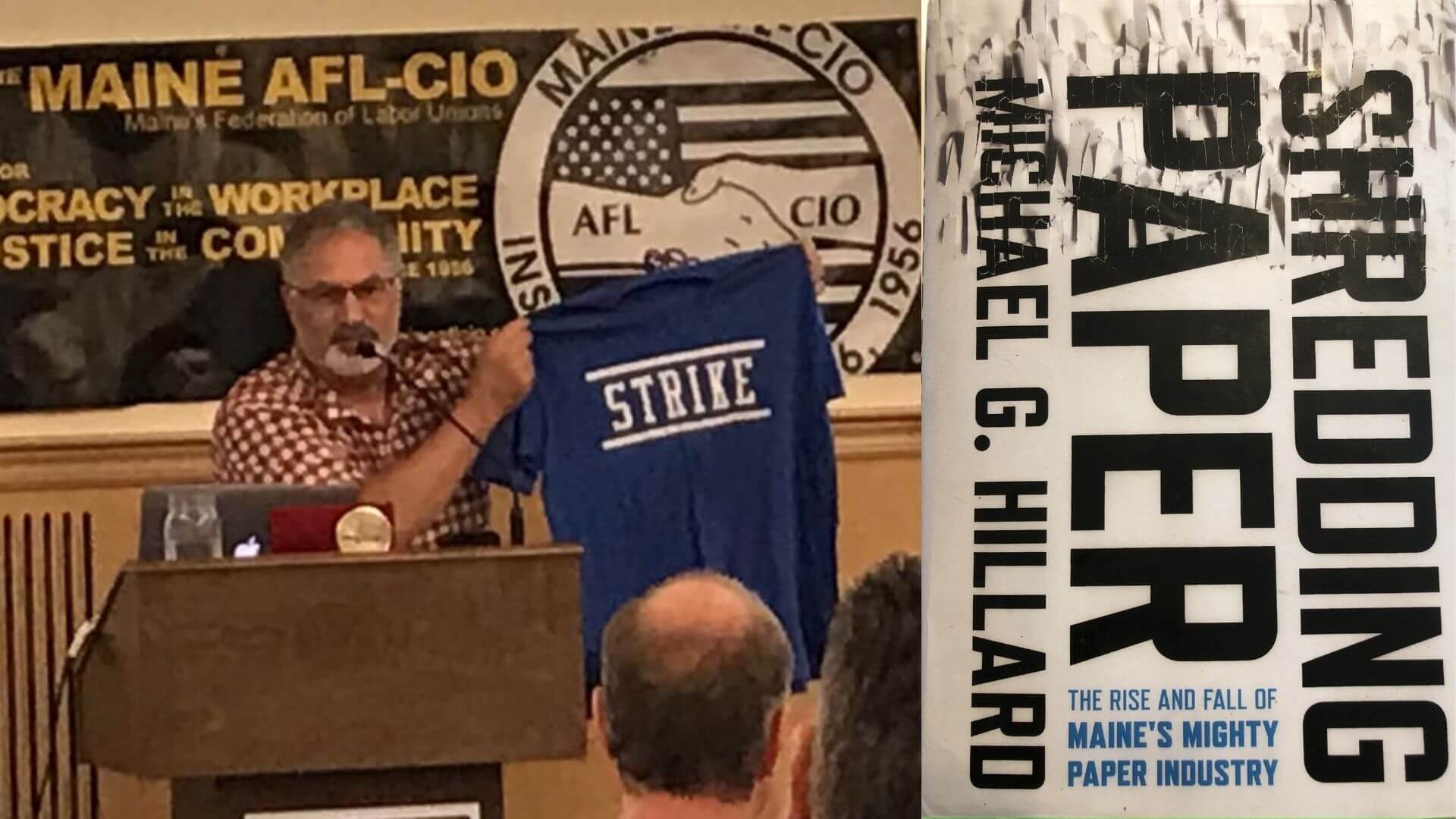

A Conversation between Emily E. LB. Twarog and Michael Hillard, author of Shredding Paper: The Rise and Fall of Maine’s Mighty Paper Industry (Cornell University Press, 2020)

I grew up not far from the banks of the Androscoggin River,[1] a river that powered the textile and paper mills of central Maine, and, every summer, I return to Maine to visit family. So, I was eager to dive into Michael Hillard’s Shredding Paper to learn more about the paper industry, a critical element of politically and economically divided state, and the workers. Shredding Paper did not disappoint. A melding of archival sources and oral histories, Hillard brings not only the industry to life but the communities that surrounded the mills. My interview with Hillard was a wild ride that took us through his thoughts on the political economy and corporate paternalism in the paper industry to networking with his students at the University of Southern Maine to find folks to interview, to his skill at transforming his academic work into popular narratives for the general public to access.

It probably has a lot to do with the fact that Michael Hillard, a recently retired professor at the University of Southern Maine, is trained as a political economist and not a labor historian that makes Shredding Paper such as excellent opportunity to understand the history of capitalism as told through a history of the paper making industry. I met Hillard years ago at a LAWCHA conference and was impressed by his ability to move rather seamlessly between the two disciplines. This is not such an easy task for many despite our frequent claims of embracing interdisciplinarity. So when I asked him how he decided to write a history of the Maine paper industry and how he navigated as a scholar when crossing the line between economist and historian, he began with Leon Fink, of course.

Michael Hillard (MH): I love Leon Fink’s quote that scholars of labor are placing a new emphasis on political economy that focuses on the “forces acting upon workers.”[2] It’s the most concise thing that I’ve ever read. It’s like, yes…that’s in one sentence that’s the best way to say it. I think the lesson of the left, whether it’s in history or political economy elsewhere for the last 50 years, is to dismiss the idea of false consciousness and figure out who people are and what they are. I thought there was a remarkable story about class formation and a particular kind of class conscious— class consciousness that was not radical, but it was class based. I tell the story in the book that the model of corporate governance that existed in the first 60 or 70 years of the industry, along with the high skill character, the particular labor process, the importance of like everybody’s involved in quality, it’s not a Taylorist kind of labor process. The way that story just kind of came together was like: they recognize that we have this corporate governance where because of our skill and because of these kind of noblesse oblige, you know, Protestant, paternalists that built the labor relations culture…

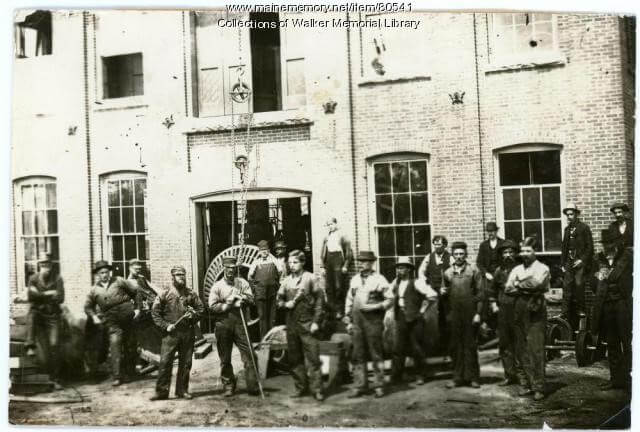

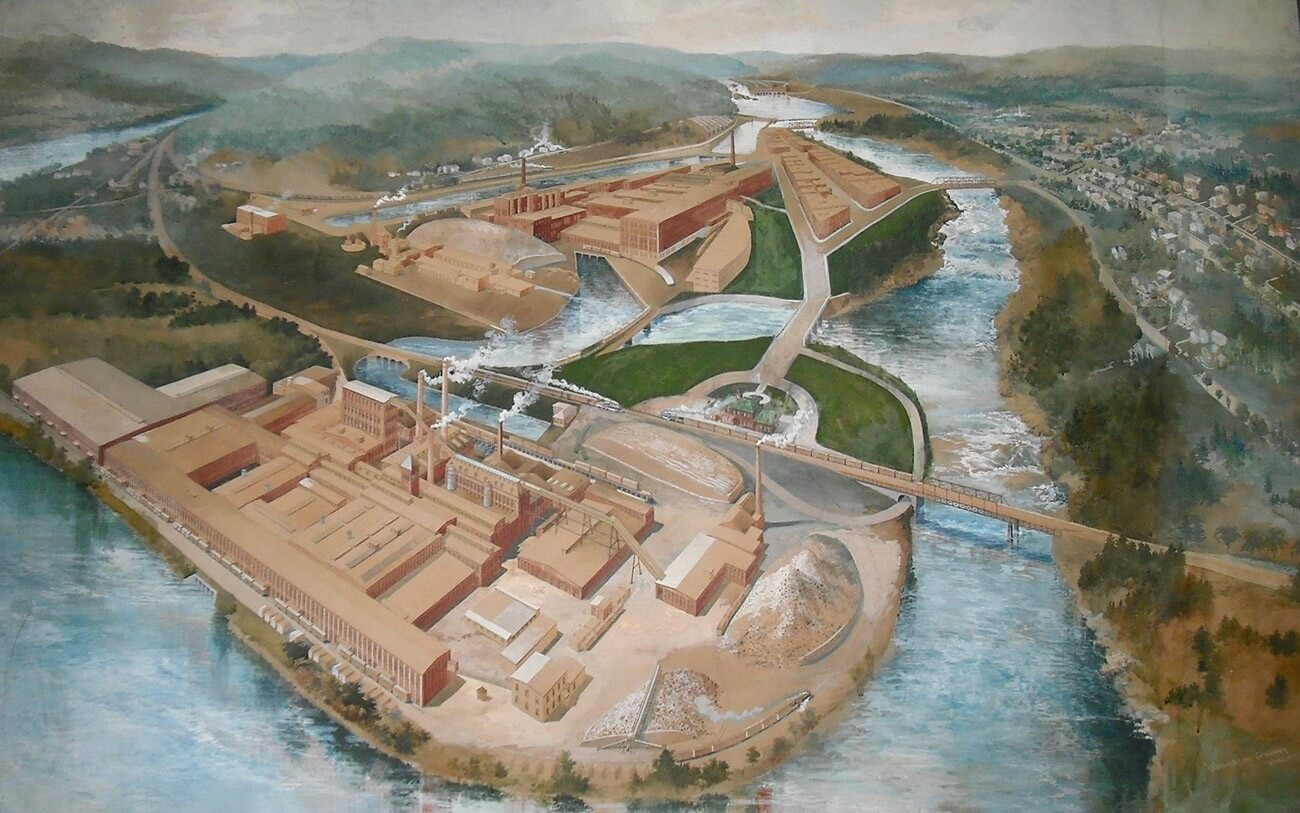

Emily E. LB. Twarog (ELBT): While the book explores the role of the paper industry throughout the state of Maine, one company dominates the narrative. In 1854, Samuel Dennis (S.D.) Warren, a Boston paper merchant, opens a large three room mill in a village that would become Westbrook in the Southern coastal area of Maine. The mill grew exponentially and by the time of his death in 1888, S.D. Warren employed thousands and was “briefly the largest mill in the world.” (21) During the turn of the 20th century, three other companies entered the paper making market in Maine – Great Northern Paper (GNP), International Paper (IP), and Oxford Paper Company, just down the road from where I grew up in another company town, Poland Spring, Maine, home to Poland Spring Water. Hillard argues that it was S.D. Warren that is “a signal case of a company that evolved from a highly informal firm into a Chandlerian company that secured its long-run growth potential.[3] It had grown prodigiously…through engineering acumen, craft skill, and a knack for identifying growing product lines…” (39) Paper production was not a low-skilled job, it required a high level of intuition and experience:

The work of producing paper that was satisfactory to the customer was highly complex. The characteristics of the ingredients water, pulp, filler, sizing, color and other materials were never exactly predictable or controllable… From the pulp mill through the paper mill, an infinite number of combinations of mechanical adjustments were possible in order to get a limited range of desired results…On the paper machines more than 100 of these adjustments were possible and less than half a dozen automatic devices had been found useful in controlling them.[4]

In Chapter Two, you write, “The company fostered and the workers embraced a system with far more resemblance to a private Scandinavian social democracy than the US’s social Darwinism— Darwinian capitalism. It was SD Warren Company’s superior commitment to its workers and their families’ security and prosperity – though one with many caveats…and a recognition and deep pride in their role in their company’s success, profitability, and reputation that secured, where most needed, an extraordinary commitment of workers’ energies and skills.” (54)

Was there something particular about Maine that allowed for this kind of welfare capitalism on steroids?

MH: I think a way of answering it is that the paternalism…was rooted in the labor process and the skills, the workers and all that stuff that I kind of try and try to put there at the center. It is definitely the case [that] the original Samuel Dennis Warren…he was sort of an esteemed Congregationalist Puritan…So I think the version of it that developed at [S.D.]

Warren happened because it was a very Anglo-workforce. What I felt like I recognized in what I learned about the town and the workers was what Sandy Jacoby wrote in Modern Manners about Kodak…

When they had the strike in 1916, there’s testimony that was reported in the [Portland]Press Herald of a worker who challenged the boss, who was the third generation of the Warrens, [arguing that it was the boss] who didn’t have their act together as leaders. [Workers] we’re like, “we’re fine Christian men and you took away our Sunday day off so we could go to church.” It was just kind of white WASP identity stuff. But the other mills in the state had very similar kinds of paternalisms. And I’m thinking particularly about a Great Northern Paper in Oxford in Rumford. And those mills were very ethnically mixed. They recruited new immigrants from the beginning Southern Eastern European immigrants. There were a lot of Franco’s [Franco-Americans Canadians], much more than S.D. Warren. And a lot of immigrants from the Maritime Provinces, you know? A lot of people from Prince Edwards Island. So they had people from all over and they had the same paternalism….

I think the way I explained it based on what I learned [from oral interviews], and I feel like I’m right on this, is that for them it was like they would have families of like ten or fifteen kids. And [they thought to themselves], “so myself and a bunch of my kids can get jobs here and we can feed everybody because the wages are high.” That was kind of a different bargain…But I think for us, places of paternalism emerged there. So, it was rooted in the labor process. I think it was rooted in a particular time, the late 19th and early 20th century; if a capitalist could afford to be a noblesse oblige paternalist they are. I think that a lot of the splits in capitalism say 1890 to 1920 is between the industries that can afford to do that and the industries that couldn’t.

The only place that was really different and distinct was Madawaska, because there was such that like the Franco-English divide— Anglo divide was so strong.

Oral Histories: The gift that keeps on giving…

One of the great gifts of oral histories is their flexibility and accessibility to everyone assuming you share them with the world. It took Hillard over fifteen years to research and write Shredding Paper and one of those reasons are the huge number of oral histories he collected and painstakingly transcribed by hand. Here are some excerpts from our interview on the gathering of the oral histories and how they have continued to be an important resource in telling the history of industry in Maine.

ELBT: Why did you decide to use oral histories in Shredding Paper?

MH: I went to graduate school for radical political economy. I studied the three volumes of Capital with really bright people. I studied contemporary Marxism and I studied a lot of economic history from a more or less Marxist perspective…But basically I like telling long stories about how capitalism as the system evolves. It is something that was just engrained in me in graduate school. Some of my professors wrote Segmented Work, Divided Workers; which was a big text at that time.[5] And I read broadly in it. So, I’ve always had an interest both through what I teach, what I studied in graduate school, and sort of long stories about capitalism and I do sit at the nexus of political economy and economics and history because I’m basically a seat of the pants labor historian. I studied with Bruce Laurie at graduate school and I think I’ve told you some of this stuff personally before; but over a long period of time, you know, what I really think I did in the last 25 years was I started to read the academic literature on labor history more closely so that I really understood the arguments and questions that people ask about working class stuff.

ELBT: You interviewed over 160 people for this project. How did you find people interview?

MH: I came here [to Maine] when the Jay Strike happened [1987-88]. I had many direct personable experiences; both as a commentator of the press and also as an activist supporting this. So, I was intrigued by that story. I didn’t know anything about the paper industry when I came up here. You know, I came to learn over—I started this sort of in the second part of my career. So the first part of my career, I learned a lot. I knew a lot of people who were in the labor movement and the Jay strike was such a big thing and I knew the direct participants really well; leadership and otherwise…

I kind of recognized that I was here and I had an organic, intellectual connection to paper and paper workers in the labor movement; and that when I decided to dig into it, really there isn’t a comprehensive literature. There’s not a contemporary book that tells the story of the paper industry as an industry with labor as a focus. But when I started, I started very modestly with S.D. Warren; you can tell S.D. Warren served my central story. It’s four miles away and I had students in my classes in the 1990s who knew that they were going to get laid off soon. They knew where they were in seniority and they were 40 years old, sort of like— “I have three years, I’ve got to get a business degree at USM” and they were telling me stories.

In the first ten interviews…I realized what an amazing story. And as soon as you start talking to people, this whole thing emerges. And, in many places in the book, people were just beating me over the head with these stories about Mother Warren. People used to get rescued by the company and the man [Warren] himself would come and give you the call. You know, it was a [Alessandro] Portelli type story. There’s this community memory and it has all these different moving parts and even had mistakes in it, which is one of Portelli’s themes, you know, mistakes that have insight kind of thing. So, I kind of started there. And then, I thought, if I could do enough kind of specific projects around the state, I could build up a story about the labor movement between 1960 and the 1990s….So I feel very happy that the oral history stuff created a vehicle to write a rich book and discover a lot of things and to write something that I could give back to the people of the state.

ELBT: I grew up in Maine, but I am not a Mainer. I moved there when I was seven so I am considered by Mainers “from away.” Did you have problems getting people to open up to you?

MH: I think there were two or three things I would say about this. One of the things that came out of this is I started to teach quantitative research; both oral history and…contemporary interviews in a bunch of my classes, because I realize it’s such a potent thing and you get students to do it. They just do two detailed interviews, and it changes them as it should…

I had really good entrees. Somebody in the labor movement establishment would interview me [and] introduce me to the key local leader, who then had a bunch of people so… introduced by somebody who trusted me and they trusted the person. I think the other thing that really came out is that…if somebody wants to come, like a professor from the university wants to come and listen to you tell your story…, it’s an act of honoring a person’s life, you know? And to sit patiently and listen to them. And it didn’t happen a lot, but a couple of times I had students who said, “Oh, interview my step-grandfather.” And then I would talk to them afterwards and just say something general, like “Hey, it was a great interview. It was fascinating. Thanks a lot.” And [the student] would say, “Boy, grandpa really likes to talk, doesn’t he?” And they were kind of like with an eye roll…That was great, you know? I think that it’s just a sort of honoring somebody by being really interested in how they lived their lives.

ELBT: Something that really excites me about your project is how you have used your research to give back to the people of the state. How did you do this beyond writing this book?

MH: I produced a “This American Life”-type long-form historical podcast on the book. I used 70 or 80 interviews across those two things to produce. I worked with professional radio producers. It’s a great way to complement what you do with the book. I guess is— when you have oral history interviews, I think it’s like a great way to share it is to tell a story that you know— and I just started doing this before podcasts was really a thing, so it turned out to be a nice thing.

In my S.D. Warren documentary, which is called Remembering Mother Warren, it’s 29 minutes. So it’s very efficient. I mean, we had a great 48 minute documentary and Maine Public Radio was only going to do 29 minutes. So, you’ll find it mind blowing because the accents— I mean, you know, Maine accents. I was interviewing, Bab and Oscar Feck who were born in 1910 or Harley Lord born in 1903 and “Well we used to call it the get up” and you hear it all over, this documentary is very cool. And let me just say one other thing; the vast majority of interviews were the kind of pay dirt ones.

And one thing I would say that might be of interest to the audience you’re running for, which is that I learned pretty early on— I had somebody— I got like a faculty grant for $500 to pay transcriptionist for the first six interviews I did and I got the transcripts back because of Maine accents, because of the idiom of the mills, they weren’t very good and so for about ten years I hand transcribed. All of them. I have upstairs in my attic. I’ve got no idea what I’m going to do with it. I had like 2,000 pages of legal pads. This is what I write on and I have a favorite black pen. Most of them were 40 – 50 pages and it was because I felt like I discovered the insights that got into what I wrote and what it produced in [the] podcast when I was hand transcribing and then looking at the way they said it, in the cadence they said it… So yeah, it was the hand transcribing, the long labor doing that. But…once I started to do it, I loved it. I mean spending an afternoon transcribing a two-hour interview. It would take me four or five hours to write out 40 pages of a legal pad—a fourteen-inch legal pad and then go through it. And then…it was so easy to write after that…

To the extent that anybody in the profession reads my book and thinks it’s valuable, I’m very honored by that. I know what it takes to read a long book like this. You know, it’s not it’s not a two-hour read at the beach sort of thing. But, you know, to write something that that again, a lot of laypeople— because the nature of Maine is that paper is really big and all of a sudden it just died over the last 20 years. And it’s a big topic in Maine culture especially if you get outside of Portland.

Over the course of our interview, Michael referenced quite a few publications related to paper production and forestry. Here is a short list of some that have been out for a while and others that have come out since Shredding Paper was published in 2020:

- Andrew Egan, Haywire: Discord in Maine’s Logging Woods and the Unraveling of an Industry (University of Massachusetts Press, 2022)

- Kerri Arsenault, Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains (St. Martin’s Press, 2020)

- Jason Newton, “These French Canadian of the Woods are Half Wild Folk’: Wilderness, Whiteness, and Work in North America, 1840–1955,” Labour/Le Travail 77, no.1 (2016).

- Monica Wood, When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine (Mariner Books, 2012)

- Timothy Minchin, The Color of Work: The Struggle for Civil Rights in the Southern Paper Industry, 1945-1980 (University of North Carolina Press, 2001)

- Julius Getman, The Betrayal of Local 14: Paperworkers, Politics, and Permanent Replacements (Cornell University Press, 1998)

- Michael Hillard’s oral history collection from this project can be found at USM Digital Commons, Papermills.

Interview conducted by Emily E. LB. Twarog via Zoom. If you are interested in the full transcript, please email me at etwarog@illinois.edu.

[1] “Androscoggin” — Eastern Abenaki term /aləssíkɑntəkw/ or /alsíkɑntəkw/, meaning “river of cliff rock shelters”

[2] See Leon Fink, “The Great Escape: How a Field Survived Hart Times,” Labor, 8(1): 109-115. Quote appears on p. 112. Hillard, Shredding Paper, 11-12.

[3] Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Belknap Press, 1977).

[4] Quoted in Shredding Paper, 56.

[5] David M. Gordon et al, Segmented Work, Divided Workers: The Historical Transformation of Labor in the United States (Cambridge University Press, 1982).

Associate Professor University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Labor and Employment Relations

Affiliate Faculty, Gender in Global Perspectives Program and European Union Center, and Co-Director, Regina V. Polk Women’s Labor Leadership Conference

Author, Politics of the Pantry: Housewives, Food, and Consumer Protest in Twentieth Century America (Oxford University Press, 2017)