Since the 1980s, Bob Rossi has been working on a social history of Colorado coal mining communities and an account of the 1927–28 Colorado mine workers’ strike. A part of this work has entailed documenting the lives of Syrian and Lebanese families in the Colorado coalfields. Rossi is a retired union organizer who had family members employed in coal mining. He recognized the need to capture these stories and thus provide nuanced understanding of the Syrian and Lebanese immigrant experience as related to the coal industry and labor strikes. With a focus on the mining communities of Walsenburg and Trinidad, the following post offers some of Rossi’s findings and details how Syrians and Lebanese helped build, benefitted from, and demonstrated against Colorado coal mining companies. This essay was originally published in the Moise A. Khayrallah Center Newsletter in September 1921. We’ll be publishing a second essay from Rossi next week.

Colorado Coal

In its mining heyday (1890s–1920s), Colorado was often ranked as the eleventh largest producer of coal in the United States and mined bituminous, sub-bituminous, coking, lignite, and anthracite coal. This coal was intended to feed the western railroads, the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company steel mill in Pueblo, the state’s powerful beet sugar industry, as well as basic industry and home and other consumers.

The Colorado coal industry was dominated by three or four companies, which essentially determined market conditions as well as the wages and working conditions of the state’s mine workers. The workers came from at least 22 different ethnic, racial, and national groups. Most lived in company-dominated coal towns and coal camps. There were as many as 12,000 coal mine workers in Colorado and as few as 8,000 at different points in the early years of the twentieth century. The southern Colorado coalfields centered around Trinidad, Aguilar, and Walsenburg, three towns that were cosmopolitan in their ethnic and racial make-up.

“Syrian” Lives in Southern Colorado

Many of the “Syrian” people in the Walsenburg and Trinidad areas came from Shweir (Choueir, near Beirut), the Beqaa Valley, Marjayoun (southern Lebanon), and the districts of Beirut and Mount Lebanon in the Ottoman Empire. The stagnation and then collapse of the silk industry and other trades, the depression of 1873–1879, and the opening of new steamship lines to Beirut drove these immigrants to leave their homelands in pursuit of economic prosperity offered by the booming Colorado coal mining industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But these economic opportunities were found amidst challenging social and cultural environments that were not always hospitable to immigrants. Thus, Syrian immigrants were forced to navigate different paths to make a place for themselves in Southern Colorado; the story of the Habib family shows some of the limitations on strategies of immigrant integration at the time.

Joyce Habib Ballotti recounted in an interview that most of the Habib family settled in Walsenburg, located in Huerfano County in southern Colorado, around 1920. Mrs. Ballotti’s father came to the United States through Ellis Island, but one of her grandfathers arrived by way of Latin America. His journey from Lebanon to Brazil, and then through Mexico and New Mexico to Colorado, took twelve years. Like Mrs. Ballotti’s family, many Syrian immigrants came to Colorado by way of other places and had worked in or owned small businesses in other coalfields and industrial regions. The Syrian communities became established by the turn of the century, with people arriving in Denver, Pueblo, Trinidad, Huerfano County, and Las Animas in the 1890s through the years of the First World War, and from Lebanon into these areas and El Paso County into the late 1930s. These communities maintained a sense of their roots and contact with other Syrian communities in the Southwest and Eastern states. Syrian households were headed by men and women. There are instances of independent Syrian women living in Walsenburg in the 1920s, including a divorced single mother who raised her three sons on her own. Upward economic and social mobility was facilitated by Syrian-Italian business partnerships as well as young Syrian men’s membership in civic organizations. Syrian participation in groups such as the Woodmen of the World, the Knights of Columbus, the Elks, the Eagles, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars suggests that these local organizations offered a way to consolidate social status and place in local communities in the 1910s and 1920s.

Syrian families in 1920s Walsenburg were concentrated on West 4th and West 7th and West 8th Streets, an integrated working-class area that they shared with African Americans, Italians, Austrians, and others. Middle-class Syrians lived on East 8th Street with merchants, skilled workers, and professionals. Relationships based on trust, family, and intermarriage seemed to have governed and typified communal relations in these coal mining communities.

For example, Mrs. Ballotti’s mother was Anglo-German. When it became known that she was going to marry Mr. Habib, members of the Walsenburg Masonic lodge attempted to stop her from “marrying that n*****,” as Mrs. Ballotti remembered hearing the Masons put it. Neither family was fully accepting of the marriage at first, and so managing family and communal relations were sometimes difficult for the couple. Arranged marriages were not uncommon among Syrians living in southern Colorado, and spouses like Mrs. Ballotti’s mother had to function simultaneously in several cultures.

Mrs. Ballotti recalled instances of discrimination experienced by the Habib family, including an episode where the postman referred to the elder Mr. Habib’s Arabic-language newspapers as “Mr. Habib’s saxophone music.” Still, the family celebrated their heritage. The elder Mr. Habib was proud that his sons maintained their Arabic last names. The Habibs listened to Arabic music, ate typical Syrian meals, and remained so focused on maintaining their heritage and identity that Mrs. Ballotti did not know the English words for spices when she married. Similar to other immigrants in the area, the Habib family owned a small business, a grocery store in Walsenburg which carried baccalà (dried and salted cod) because it was common to so many cultures represented in the town. The Habib and Ballotti families were near the centers of Syrian-Italian and mine worker-small business relations that helped give the mining communities of southern Colorado their cosmopolitan characteristics.

Little evidence suggests that Syrian mine workers remained employed in the mines for long periods of time. It seems that the Syrian men who worked in the mines used that employment to establish themselves and then moved on to owning local markets, taverns, bakeries, sheep and cattle ranches, and other businesses such as bookkeeping and bartending. Many mine workers in Las Animas County in southern Colorado bought their work clothing from “Syrian” peddlers, and Syrians had stores in Segundo that catered to mine workers and their families. Syrian men were also independent shoemakers and photographers in the region in the 1920s (2). In the 1920s and 1930s, young people from Eastern and Southern European and Syrian families began to marry and form families, and there were declines in the blue-collar populations in most mining communities or increased transience and itinerancy across the mining and farming regions. Going against these trends, we see Syrian people graduating from universities and returning to Las Animas and Huerfano counties to take over family businesses and engage in ranching, many keeping their Arabic names in the process.

The Faris family offers another example. This Syrian family owned a store in Talpa, a community northwest of Walsenburg. Mr. Asperidon Faris was the town’s first postmaster. Talpa was renamed Farisita in the early 1920s in honor of Jeannette Faris, who was then a child. She later taught in local schools, assisted in running a family ranch, became a businesswoman, helped set up community healthcare, and was active in the Republican Party. She also did much to preserve local history. Other notable families include the Sawaya family of Trinidad. In 1912, Joseph Sawaya, who got his start carrying bags of groceries to the mines, opened a wholesale grocery business, which continues to serve the southern Colorado area. Joseph’s son, George Joseph Sawaya, became a well-known saxophonist in the region and began performing professionally in the mid-1930s when he was eight years old. The founders of Hadad’s Home Furnishings in Trinidad (now closed) began their business as peddlers in Segundo in the 1910s and, as of the 1990s, still felt gratitude for regional mine workers’ support over the years. Similar to other Syrian immigrants, the Haddad family anglicized their name when they first immigrated to the United States. Hadad family members still work in Trinidad as merchants, car dealers, and real estate owners.

UMWA coal miners on strike against CF&I, in Ludlow, Las Animas County, Colorado, pose with onions, celery, bread, a full gunny sack, and a washtub full of spinach. Courtesy of the Denver Public Library.

UMWA coal miners on strike against CF&I, in Ludlow, Las Animas County, Colorado, pose with onions, celery, bread, a full gunny sack, and a washtub full of spinach. Courtesy of the Denver Public Library.

Yet not all of the business partnerships were helpful to the community. Ethnic and inter-ethnic conflicts occurred in the coalfields. Young Syrian men from Walsenburg, Aguilar, and Trinidad were often engaged in altercations with one another and others. An Italian store owner in Trinidad murdered a young Arab man in 1918. A street brawl near the corner of Main and Sixth Streets in Walsenburg in 1922 was attributed to Turkish people from Denver who had allegedly come to Walsenburg well-armed in order to settle scores with others.

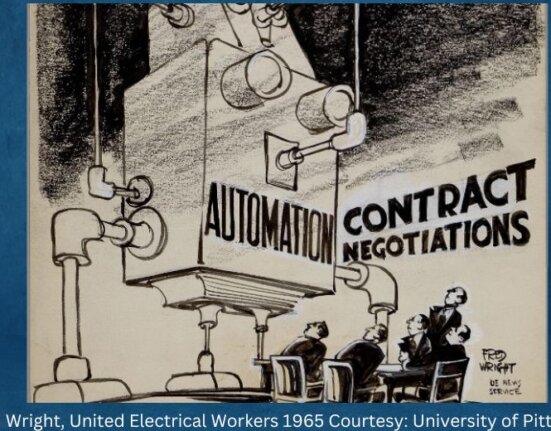

Syrian mine workers participated in a number of union and worker-led coalfield strikes. Such strikes occurred in most years between 1900 and 1928, but there were especially dramatic strikes between 1910 and 1914 years, 1919–1922, and 1927–28. The 1927–28 strike was led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and involved members of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) and the Communist-led National Miners Union (NMU). Syrian workers had participated in other industrial strikes across the country, and word of these union organizing efforts no doubt circulated through family networks and the Arabic-language press (3). It seems likely that knowledge of these union organizing efforts conditioned the Syrian responses to the 1927–1928 strike in Colorado. While Syrian people were not central to the labor and strike movements in Colorado’s coalfields, recognizing their contributions and understanding their relationships with other ethnic, racial, and national groups is necessary to fully comprehend the state’s coalfield communities.

Concluding Thoughts

Life in Colorado’s coal camps and towns revolved around the schedules and rhythms of the mines. Workers sought to maintain and win forms of worker and union control in the mines while working-class people in the coalfields attempted to create democratic social structures in their communities; Syrian workers and small businesspeople established essential relations of trust with other immigrants and mine workers. Their family and communal lives demonstrate how working-class immigrants faced and responded to challenges such as particular forms of patriarchy, isolation, discrimination, and enforced conformity.

Mine workers’ on-going struggles to wrest control of their working conditions and win wage increases were accompanied or mirrored by efforts in coalfield communities to create democratic communal space and institutions. Mrs. Ballotti and others with whom I spoke recalled family meetings that made decisions together (rather than just by the patriarch), small businesses extending credit to strikers (and sometimes going bankrupt as a result), and informal and egalitarian relationships with others that marked relations of solidarity, as suggested by the story of the single mother mentioned above. When taken together, these efforts can be seen as building communal identities and solidarities that helped make unionism and strikes possible in Colorado, and that helped create and maintain unique coalfield cultures that have withstood coal mining’s decline.

A Note on Sources

*This work incorporates information found in local census records, city directories, and newspapers relating to Walsenburg, Trinidad, Aguilar, and Farisita. I also consulted online databases such as Ancestry.com and Find-A-Grave.com. An interview I conducted with Joyce Habib Ballotti in July 2016 provided critical information, as did an email exchange with Michael G. Sawaya in June 2021.

- The term “Syrian” refers to immigrants who came mainly from today’s Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine/Israel.

- Photographs taken by Syrians are difficult to find. In 1906, Walsenburg passed a still-existent law restricting itinerant photographers, likely intended to make the Syrian’s work more difficult. There are plenty of photos of the time not taken in studios, but these images have no identifiers. Many Walsenburg studio photos lack identifiers as well.

- Syrian mine workers were active in the Bingham Canyon, Utah mines in 1912, when militant union organizing was underway, and Syrian workers were important to the textile strikes led by the IWW in Massachusetts and New Jersey in the 1910s. The 1912 textile workers strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts and the Bingham Canyon organizing were in some ways foundational to working-class Syrian identity in the United States and acquainted these workers with industrial unionism.