David Witwer and Catherine Rios recently published Murder in the Garment District: The Grip of Organized Crime and the Decline of Labor in the United States. It tells of racketeering and union corruption in 20th century New York, when unions and the mob shaped working class lives. Randi Storch recently interviewed Witwer about the book.

Your book focuses on organized crime and New York City’s garment unions in the 1950s. We normally associate the Teamsters with organized crime. Why is it important that we understand the relationship between organized crime and garment unions in this period? Can you discuss the overlap between labor and organized crime more generally in New York City in this period?

I think it is important to understand the relationship between organized crime and the garment unions in this period because that relationship challenges many of the long-held assumptions about labor racketeering. As your question acknowledges, people tend to associate the Teamsters with organized crime and in so doing they assume a connection between the pragmatic, business unionism embraced by that union and the problem of corruption and labor racketeering. Indeed, I think the image that typically comes to mind is that of a truculent, cynical Jimmy Hoffa—which I believe is more of media construction than an accurate image of the real Hoffa—and behind all of this lies an understanding of labor racketeering that essentially blames the victim. Crass union members elected crass union leaders like Hoffa, who made self-serving deals with organized crime. This kind of critical generalization draws on negative stereotypes about the working-class and their leaders that William Puette highlighted in his book Through Jaundiced Eyes: How the Media View Organized Labor. In my research, I have seen similar media tropes emerge as early as the turn-of-the-twentieth century.

The garment unions, specifically the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union, present a challenge to those assumptions about labor racketeering. They were led by political progressives, whose unions aspired to loftier goals than what we would tag as business unionism. In the ILGWU, the majority of the members were women, and much of the leadership, from David Dubinsky on down, had ties to socialism or communism. At least in terms of public image, we can almost think of Dubinsky as the anti-Hoffa and the ILGWU as the opposite of the Teamsters. And yet, as the book tries to demonstrate, the leadership of the ILGWU found itself having to accommodate elements of organized crime in ways that resembled the patterns of labor racketeering that existed in parts of the Teamsters Union.

The lesson that we want readers to get from the book is that the problem of endemic corruption that existed in some sectors of the labor movement had little to do with the ideological or moral failings of union members or their leadership. It had to do with the embedded role of organized crime in particular urban sectors and particular industries in post-World War II America. The corruption that existed in labor fit within larger systems of corruption that were rife in politics, law enforcement, and business. We hope the book serves as a corrective to an understanding of union corruption that became dominant in the 1950s, as a result of the McClellan Committee hearings, and especially the way that those hearings were framed by Robert Kennedy to focus on Hoffa and the Teamsters.

As we explored in Chapter Seven of the book, the internal reports of the McClellan Committee’s investigators (which only very recently became available to researchers) provided a very different perspective on organized crime’s role New York City’s labor movement. The mob was embedded in industries where businesses had long relied on various cartel arrangements to manage competition—such as waste removal or construction. The mob also had a role in the so-called paper locals, predatory unions that sold small, low-wage employers sweetheart contracts which those businesses hoped would keep legitimate unions at bay. In both cases—the cartel arrangements and the paper locals—the mob was licensing (or taxing) an ongoing illegal arrangement in a similar manner to how organized crime profited from say sports betting or the numbers.

The McClellan Committee hearings depicted Hoffa and the Teamsters as playing a central role in the creation of the paper locals, but the reports of the committee’s investigators told a very different story. The officers of these locals were typically petty criminals who moved their organizations from one national union to another, shifting in response to a range of pressures and incentives. They existed in New York City long before Hoffa’s rise to national leadership, and the Teamsters was only one of several unions that ended up with such locals.

Your examination exposes a contradiction between the way the government and the public came to view labor racketeering and the on the ground reality of racketeering. Why is this difference so important to understanding what happened to the post-war labor movement?

High profile investigations, in particular the McClellan Committee hearings, portrayed union corruption as an a union issue, largely ignoring the business and political environment in which it tended to occur. The public was taught that the cause of labor racketeering was the moral failings of a significant proportion of the leadership of some of the most powerful unions, especially the Teamsters. Because of this framing of the issue, unions could be portrayed as exploiters rather than protectors, from which the hapless working-class needed protection.

For groups opposed to organized labor, including the National Association of Manufacturers, this understanding of union corruption provided them with leverage to win wider support for new restrictions on union power. This understanding of union corruption became a wedge issue, one that organized labor’s opponents could use to separate liberals from their allies in the union movement. George Meany highlighted this phenomenon in 1959, after Congress passed the Landrum-Griffin Act, which included potent new restrictions on union organizing and strike tactics. Meany noted that many of the liberal Democrats who voted for this law had won re-election the year before with union support. But when it came to voting on a bill that purported to curb union corruption, those liberal Democrats helped pass legislation inimical to union power.

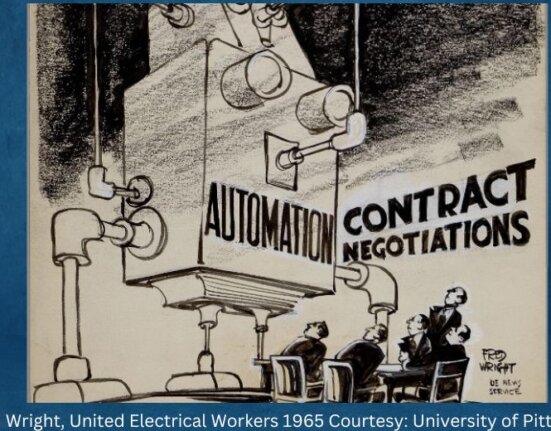

Like the Taft-Hartley Act, which also drew on concerns about union corruption, the Landrum-Griffin Act had both symbolic and strategic importance. Both laws promoted a negative view of organized labor as a potentially nefarious force from which the community needed protection. Both laws imposed limits on union tactics, such as secondary boycotts, which had played a pivotal role in allowing organized labor to expand into regions and business sectors that had long resisted organization. Taking those tools away from organized labor did not lead to an immediate decline in membership numbers, but as Nelson Lichtenstein pointed out so well in State of the Union, it helped seal the movement’s doom. Organized labor was left restricted to particular economic sectors, such as manufacturing, and particularly regions, essentially “balkanized,” I think was how he put it. When those economic sectors went into decline, the union movement declined with them. Then too when legislative proposals are put forward to facilitate union organizing, the specter of union corruption is invoked to weaken political support for such changes.

One of the fascinating aspects of your book is the way in which racketeering touched the lives of a wide assortment of people –those completely committed to social justice and those bent on exploiting vulnerable working people. Can you elaborate on that fact and talk about some of the more interesting individuals and how they experienced racketeering?

One of the most intriguing relationships that we came across in our research involved Min Matheson, an idealistic official in the ILGWU and Abe Chait, a notorious gangster. Matheson’s father had been a radical in Russia and was active in the Socialist Party in Chicago once he emigrated to the U.S.; and she grew up in a very politically engaged household, attending a Socialist Sunday School, for example. As a teenager she joined the Young Communist League and it was there that she met her future husband. Even after she left the party, Matheson remained committed to the progressive causes she had grown up with and so she eventually landed in the ILGWU, where her mentor was Charles “Sasha” Zimmerman, who had at one time led the Communist faction within that union. But when Matheson came to lead the ILGWU’s organizing efforts in Northeast Pennsylvania she found herself working closely with Abe Chait, who ran several trucking companies and had become the most powerful Jewish organized crime figure the Garment District. For his part, Chait had apparently decided to make an alliance with the ILGWU, helping them organize mob-connected trucking firms, in return for more lenient contract terms for those firms.

For us the story of Matheson and Chait’s relationship highlighted a central theme in the book that the usual true crime archetypes—the heroes, villains, and martyrs—that one usually encounters in books on labor racketeering don’t really capture the real complexity of the situation.

The story of Victor Riesel is another example of this theme. In standard accounts of this period, he is invariably depicted as the martyred, heroic journalist who was blinded by an acid attack in 1956 because of his crusade against labor racketeering. We drew on FBI reports obtained via a Freedom of Information Act Request to show that Riesel was far from being a heroic crusader, instead he was taking money from labor racketeers in order to keep their names out of his newspaper column. He himself had close ties to one of the most prominent labor racketeers in the Garment District. We found that the FBI kept this information to themselves and the McClellan Committee also avoided tarnishing Riesel’s public image because as a martyr he served their needs.

You argue that today’s negative impressions of the labor movement are connected to the events you examine in your book, including the McClellan hearings and public messaging of all unions as corrupt. Which people are most swayed by this argument that unions are inherently corrupt and from where are they getting the message? Which are the most important lessons of the story you tell for labor today, especially regarding the question of union corruption, and to win the public’s trust?

I believe that people who have little direct connection to unions—which is the majority of Americans today—are often swayed by the argument that unions are inherently corrupt. I think of my students in this case. I work at a branch campus of Penn State and a large proportion of my students are first generation college and/or working-class, but few of them have any familiarity with organized labor. Many of them work part-time, or even full-time at various big retailers, restaurant chains, local grocery chains, or other similar corporations—all of which are staunchly anti-union. When we have talked about the history of organized labor in class, many of them will say that what they have learned about unions came from the orientation presentations and videos that they sat through when they started their jobs. Or they might refer to various movies and television shows, for instance the recent Netflix film, The Irishman, which portray unions as little more than an extension of the mob. As my colleagues in American Studies might put it, there is a prolific folklore of union corruption that circulates in popular culture and shapes popular attitudes. You can look at Lawrence Richards’s book Union Free America: Workers and Antiunion Culture for a more academic exploration of these attitudes and their impact on working Americans.

I think the most important lesson my work might offer to labor today is the need to address this issue directly. My own sense as an historian writing about this topic is that the preference within labor circles is to avoid this topic and by extension pretend the problem of union corruption does not exist. This is pretty much what the AFL-CIO did after the McClellan Committee hearings came to an end. The labor federation quietly walked away from its own internal anti-corruption effort, which had been the Ethical Practices Committee, and allowed that group to fade away into obscurity. But corruption did not come to an end, and when a new set of scandals emerged, especially in the wake of Jimmy Hoffa’s disappearance in 1975, labor was left to appear indifferent to corruption. I think this is a recurring pattern, one that you can see playing out most recently in the United Auto Workers Union.

I would prefer to see labor engage directly with the history of union corruption and consider pro-active measures that could be adopted internally to address the problem. Such measures won’t eliminate corruption, which is a problem that occurs in every sector of society. But taking these measures may help abate, or limit, future corruption scandals, and perhaps more importantly they could bolster labor’s image in ways that counter-act the current, dominant folklore of corruption. I guess what I am saying here is, instead of reacting after-the-fact to the outrage generated by scandals, I’d like to see labor take a stand and say, corruption is part of our history, one that has been manipulated and misrepresented by our opponents, but it is still an issue that we want to address. In order to address that history, we will take a serious look at the history of corruption and frame up an ongoing set of measures to counter this problem.

Now that your book is published, what books are you looking forward to read?

Well, I’m already off and running on my next book project, which will be on the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa, but also more broadly about the myth of Hoffa that has had such a prominent influence on labor’s public image. This means I’ve been reading a lot of true crime books, which I see as the typical way most Americans encounter Hoffa, and more broadly the topic of labor racketeering. But I would say, if folks are looking for reading recommendations on this subject, I was quite impressed by Jack Goldsmith’s recent book In Hoffa’s Shadow. Goldsmith has done really impressive research and he writes a very compelling narrative. I also think Steven Brill’s 1978 book The Teamsters offers a kind of wide ranging survey of the union, and its role in the lives of actual workers, that is really quite rare.