We are now in the 50th year since the appearance of Strike!, one of the most influential books written in the New Left era, and one so sweeping in its depiction of direct action that it has become a textbook of sorts for every radical generation since. A new revised and expanded edition (PM Press) reminds me that vivid prose never loses its appeal, but also that labor history, a field slipping away from public attention all this time, is also social history, community history, and a history as much outside of as within the organized labor movement.

Now a policy and research director for the Labor Network for Sustainability, Brecher focuses much of his interest upon survival of the planet’s ecosystems, but also on the nonviolent mass action that will be required to make this goal achievable. In the new volume Common Preservation in a Time of Mutual Destruction (PM Press) as in an earlier work, Save the Humans? Common Preservation in Action (2020, also PM), Brecher is very much on message. But some of the most fascinating and for this reviewer, also the most puzzling pages for this reviewer, find the author describing his own life in the struggle. His parents were mainstream journalists who quit the rat race to become freelancers, with all the attendant anxieties. He mostly grew up in Connecticut, a picturesque middle class redoubt not all that far from what quickly became known as a former manufacturing area gone to hard times.

Brecher’s big move from college was to the Institute for Policy Studies, a leftish think tank in DC, and from there, he could take part in an extended series of social and political mobilizations, peace projects including Vietnam Summer among the best known. In my view, this experience placed him as a lifelong mobilizer, but he had also learned from his patents the need to write clear and forceful prose to get and keep the reader’s attention. Save the Humans rolls out the compelling saga of Brecher seeking a great mystery, above all to the Left: how informal groups get together to make change, from the factory floor to the community and beyond, the last point especially compelling in an age of ecological crisis. The “Liliput Strategy” that he proposes relies upon making the aims of the powerful too difficult, too expensive, too threatening to actually bring into existence. Globalization from Below, a strategy as well as a title of one of his books along the way, makes the struggle for a different kind of world a needed counterpart to any environmental solutions.

Common Preservation flows from these notions. Brecher begins the book with another childhood memory, his reading of the historical novel by the once-famous (also once imprisoned) leftwing writer Howard Fast’s slavery escape novel, Freedom Road. Eric Foner, famed radical scholar of Civil War era history, has pointed to the same book, both youngsters grabbing the volume from their parents’ bookshelves. Fast led Brecher, he tells us, to W.E.B. Du Bois, whose Black Reconstruction, appearing in 1935, was too radically antiracist for its time and only accepted by mainstream US historians thirty or forty years later.

Du Bois’ sweeping narrative first led Brecher to search out the mysteries of massive social changes. And we learn here that he intends to spend most of the volume explaining to us his thinking of systems of thought, philosophy and psychology to science and beyond, bringing together ideas that may make the daunting task of out-organizing the global capitalist system possible.

Many readers, and I am surely one of them, will find his description of his development of ideas unique or even idiosyncratic. We oldtimer radicals have constructed our ways to rethink politics and mobilization by very different methods. But so what? That these are his ways is more than enough to sustain our interest in the thinker and activist.

His very particular past accounts, I think, for his uniqueness. Joining the Institute for Policy Studies set him toward theories of group dynamics, theories kicked around more by organizers than by those being organized. Saul Alinsky’s methods empowered Cesar Chavez and the farm workers, and many would say, helped to lay them low by the concentration of power from the top down. (For that matter, and tragically, Gene Sharp, the keen strategist of non-violent mobilization, has in recent decades become a favorite reading for Regime Change methods of the State Department, aimed at the leaders of nations deemed unfriendly to US interests. Methods have their own logic.)

Thus as Brecher recalls, for instance, that as he early developed his explored “ways of thinking from pragmatism to cybernetics,” he came to the relationship of Jean Piaget’s theories of childhood development with today’s complexity theory. Further along the way, he takes up mathmatical notions and systems theory, among others, defining and using these ideas in his very own way, sometimes separating them from their originators, occasionally inventing his own neologisms along the way. “Equiliberation,” which comes at the climax, may be the sum of what he has in mind, an equilibrium that liberates.

I stumble badly over his fondness for John Dewey, whose contributions to public education remain vital, but whose philosophy of Pragmatism, liberating thought from fixed categories into ideas that may actually work, has never been separate from the burden of its context. As a young socialist critic wrote in the 1910s, Pragmatism was immediately understood as the American antidote to Marxism, the philosophy of dialectical change. Dewey’s embrace of the conquering US role in the First World War made as much sense, in these terms, as the opposition of Rosa Luxemburg to war and empire alike. Pragmatism sought to make rational what could also be described as unendurable. Dewey offered significant proposals for domestic reform, especially during the New Deal. And then he fell back into his hawkish role in the Cold War, shocking progressives once again, reminding many observers of another famed thinker, theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who shifted from 1930s socialist to the 1950s father of neo-conservatism.

By contrast, I think I can grasp “Open Systems,” explained by Brecher, as coming closer to the vital need to understand the functioning of ecosystems, an understanding that emphatically includes humans freed from their own craving for domination. In the place of domination, Brecher recalls the title of an earlier book, Globalization From Below. Reading and pondering Gandhi as Brecher developed his ideas, prompted him back in the direction of Piaget, seeking an analogy between the development of the child’s adaptation and the potential development of social adaptation (or “equiliberation”) to take on and replace existing systems of power. He views the rise of Occupy Wall Street as a a common action that “provided a new kind of feedback that revealed their existence as. group” and “from this they began to construct representations of themselves as. group.” (p.102). I hear the sounds of Jean Paul Sartre rather than Piaget, but appreciate what Brecher is striving to explain and explore.

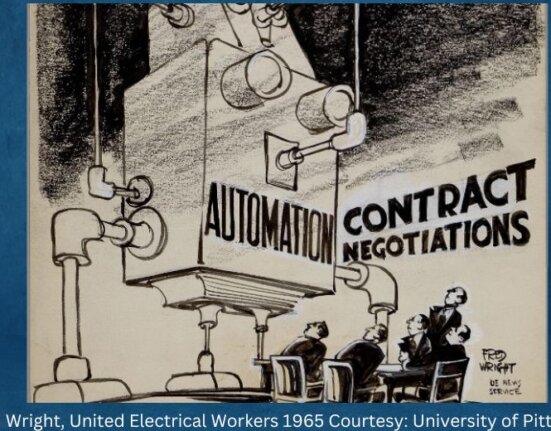

An intriguing section of Common Preservation offers Brecher’s notion of “tools” and his discovery of the mathematician G. Polya, a popularizer of the term “heuristics.” If a problem can be properly identified, proposals offered and a feedback loop created, minds can be moved toward a goal, most especially climate change. He offers his own example as explained in Building Bridges: The Emerging Grassroots Coalition of Labor Community i(1992) in his home space of Connecticut’s Naugatuck Valley, where the mills came and went, leaving a deindustrialized population grappling with their own fate. His heuristic search for solutions, he believes, helped to develop ideas for alternatives in the post-industrial life of residents.

He strikes what is perhaps his major chord when we come to the KXL Pipeline struggle. Here, the odds against stopping an ongoing decision of very major corporations and their supporters in both political parties but also the unions involved seemed daunting in the extreme. The intellectual leadership of Bill McKibbon, the alliance pulled togehter across the Sierra Club, Julian Bond, the Hip Hop Caucus and a wide swath of on-the-ground activists willing to engage in sometimes extreme non-violent protests pushed Obama into what he would not likely have done otherwise, to call a halt.

The painful reality is that, as Brecher says, the coalition “was unable to overcome the power of the state, property rights, markets and the fossil fuel industry.” (p.254) This defeat actually prompted the environmental movement into alternative visions. As a participant, Brecher lays out his own experience and observations. Following the success of the first environmental movements back in the 1960s-70s, he points to the public trust doctrine, and “old and widespread legal principle” (p.262) that can allow civil disobedience in the name of a higher law than the ones on the books. The government has a duty to protect the common environment, and a movement that can establish that duty has a shot at halting, even reversing, the catastrophe not far ahead.

This is an excellent argument and Brecher details its ramifications lucidly. We might make the same argument, reach for the same goals, without his philosophical guidelines. Again, so what? He has led a life to help us mark the way forward, if only we are in time.

**********************

Paul Buhle is, most recently, editor of Ballad of an American, the graphic biography of Paul Robeson, drawn by Sharon Rudahl.