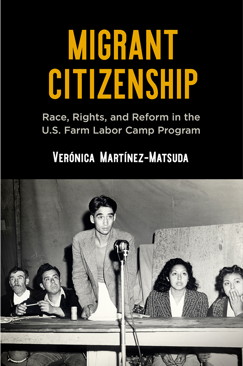

Our series of interviews with authors of new books in labor and working-class history continues with Verónica Martínez-Matsuda. The University of Pennsylvania Press published her Migrant Citizenship: Race, Rights, and Reform in the U.S. Farm Labor Camp Program in June. Martínez-Matsuda, an associate professor in the Department of Labor Relations, Law, and History at the Cornell ILR School, answered questions from Jacob Remes.

Your book is called Migrant Citizenship, which at first glance seems like a contradiction in terms. How did farmworkers craft a version of citizenship that didn’t depend on immigration status?

That’s right. Its contradiction was the very problem farmworkers and Farm Security Administration (FSA) officials tried to resolve through the camp program. During the 1930s and 1940s, stringent state and local residency laws, combined with deep-seated racial and class prejudice, left migrant farmworkers without a place to enact their basic rights. Even if they were formally U.S. citizens, farmworkers were regularly denied the right to vote, send their children to school, access public aid, and receive medical care because they were considered non-residents or non-citizens of the community and state in which they were seeking services. The transitory nature of migrant work, in other words, marked all farmworkers as “alien.” A big part of this story, therefore, involved uncovering how FSA officials and migrant families challenged the notion of juridical citizenship as a guarantor of democratic rights. Together, they argued that real democracy resulted not only from migrants’ full enfranchisement but also from their daily participation as citizens (regardless of formal status) in a political and social community characterized by collective responsibility and behavior.

Is there a character in your book you’re especially fond of?

There are truly so many fascinating individuals in this historical account. That’s part of what made this program extraordinary. For a long time I was fascinated by Laurence I. Hewes, Jr. He struck me as someone who clearly embodied why a race-relational analysis of the camp program is necessary. In 1935, Hewes began working for the Resettlement Administration (RA) in Washington, D.C., paying particular attention to the dislocation impacting white and Black tenant farmers and sharecroppers in the South. In 1939, after the RA becomes the FSA, he is sent to San Francisco to serve as the agency’s Region IX Director. In 1942, Hewes is busy overseeing the expansion of the labor camp program in the West when he’s called in to help coordinate the evacuation and relocation of all persons of Japanese ancestry on account of E.O. 9066. Among other things, Hewes oversaw the operation and sale of Japanese farms, and worked with FSA architects to design World War II internment camps. Within months of commencing these operations, he is also sent to Mexico City to begin negotiations for a new Mexican Farm Labor Supply Program, better known as the Bracero Program. That one man could traverse this terrain seemed astonishing at first, but it really is a clear example of how these processes and the struggles they produced overlapped in significant ways. The last thing I’ll mention is that Hewes wrote a memoir later in his life titled Boxcar in the Sand, which is super interesting because he’s very candid about how he felt in carrying out these assignments.

Because things like the Wagner Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act and Social Security excluded farmworkers, we often describe the New Deal as excluding them. But you describe the Farm Security Administration as a profound “experiment in democracy” seeking to include farmworkers. How does close attention to the FSA change our view of the New Deal as a whole?

Yes, it’s true that farmworkers were excluded from these key New Deal protections. I’ve written more in recent times, particularly concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, about the costly consequences of federal inattention to farmworkers’ welfare and the racist origins of that. It’s one, of so many, examples of systemic racism at play. The simple fact is that the Southern congressmen who were central to advancing the New Deal because they dominated Congress did everything they could to preserve Jim Crow and deny Black workers any opportunity to challenge their condition. And, quite significantly, this exclusion served in the interest of industrial farmers in the West where the expansion of commercial agriculture had become profitable through the exploitation of mostly Mexican and Asian labor.

Thus, when the FSA establishes its migratory labor camp program and begins investing in farmworkers’ well-being—that is, by arguing that all farmworkers should be entitled to political representation, fair wages, good housing, public education, medical care, and the human dignity they were so often denied—it directly challenges the nation’s agrarian establishment and status quo. Part of why this is important to recognize is that it shows how the FSA’s reformist, democratic project reached far deeper and wider than previous scholars have acknowledged. It also changes the New Deal’s political narrative by demonstrating how some New Deal liberals developed meaningful reform action through the 1940s, and within a rights-based framework that addressed matters of racial and class injustice as central.

For a while now, people have been demanding a Green New Deal, and mass unemployment from Covid has brought even more discussion of a “new New Deal.” What can the experience of farmworkers during the original New Deal tell us about how we might craft a new one?

I’ve certainly been thinking more about this as well, particularly as we consider how the nation will recover from the economic crisis fueled by COVID-19. I’ve seen good discussions of this on social media, some of which include bringing back New Deal programs like the “Works Progress Administration” and others. I don’t think that’s a bad idea so long as these programs are more equitable today than they were then. But these days, I’m actually more inspired by the research I’ve been doing on farmworkers’ “self-help” programs under the War on Poverty. And, in particular, by the challenges surrounding the Community Action Programs of the 1960s and 70s. We’re currently witnessing the incredible strength of community self-organization and determination in many forms—in everything from the establishment of new mutual-aid groups to the #BlackLivesMatter movement. That’s why I think we should consider investing more in local communities’ own strategies for supporting and empowering people, especially those that are unemployed, facing food insecurity, or lack healthcare. Unlike the original New Deal, I certainly hope this time around the most vulnerable aren’t left out simply because it’s what’s politically palpable and profitable.

Now that you’re done with your book, what are some books you’re looking forward to catching up on?

Oh, there’s so much to catch up on! I’m especially excited to read José M. Alamillo’s new book, Deportes: The Making of a Sporting Mexican Diaspora. José is a fellow Dodger fan so I know what he’s written is brilliant—ha-ha! I’ve also been hoping to read Eduardo Contreras’ Latinos and the Liberal City: Politics and Protest in San Francisco, which won the 2020 David Montgomery Award. And, I recently heard a great interview on NPR’s Code Switch with Karla Cornejo Villavicencio that made me want to order her new book The Undocumented Americans. But, to be totally honest, these days I’m mostly reading from the bookshelf my three six-year-olds curate. I’ve learned a lot about Star Wars in the last few months!