Our series of interviews of authors of news books in labor and working-class history continues. Philip F. Rubio’s latest book, Undelivered: From the Great Postal Strike of 1970 to the Manufactured Crisis of the U.S. Postal Service was published in May by UNC Press. Rubio is professor of history at North Carolina A&T University; he answered questions from Jacob Remes.

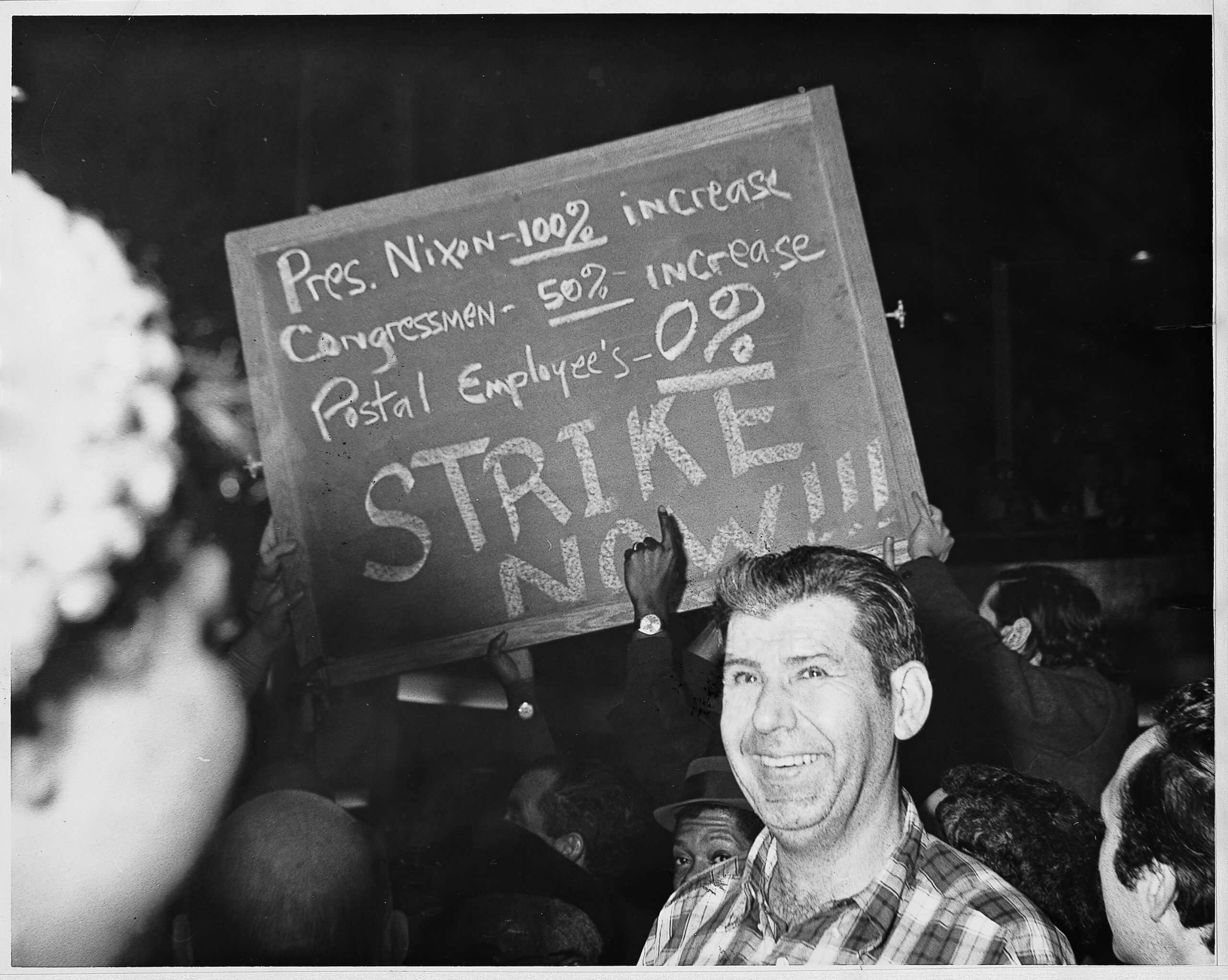

The 1970 postal strike seems especially exciting because it was a wildcat among workers who defied their bosses, the courts, and even their union leadership. How was this sort of rebellious strike able to spread and last?

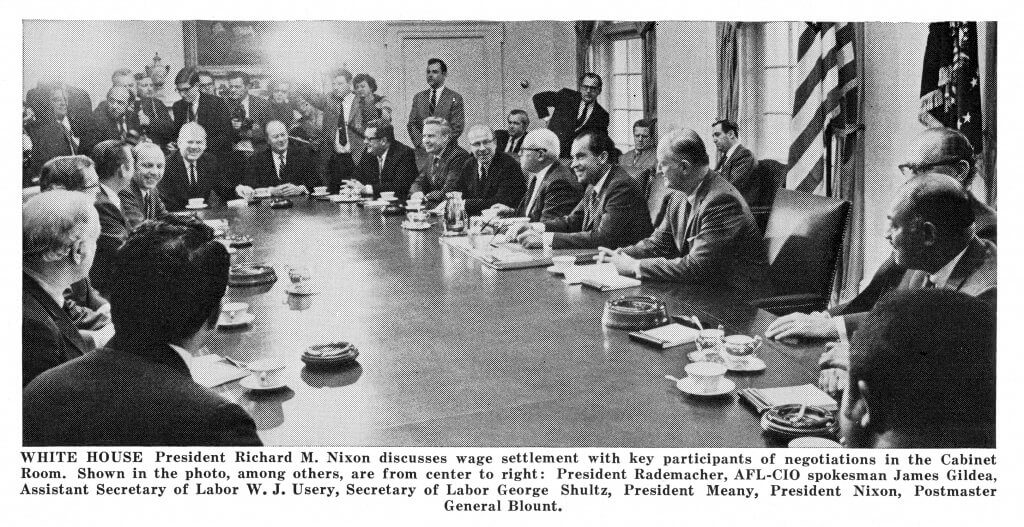

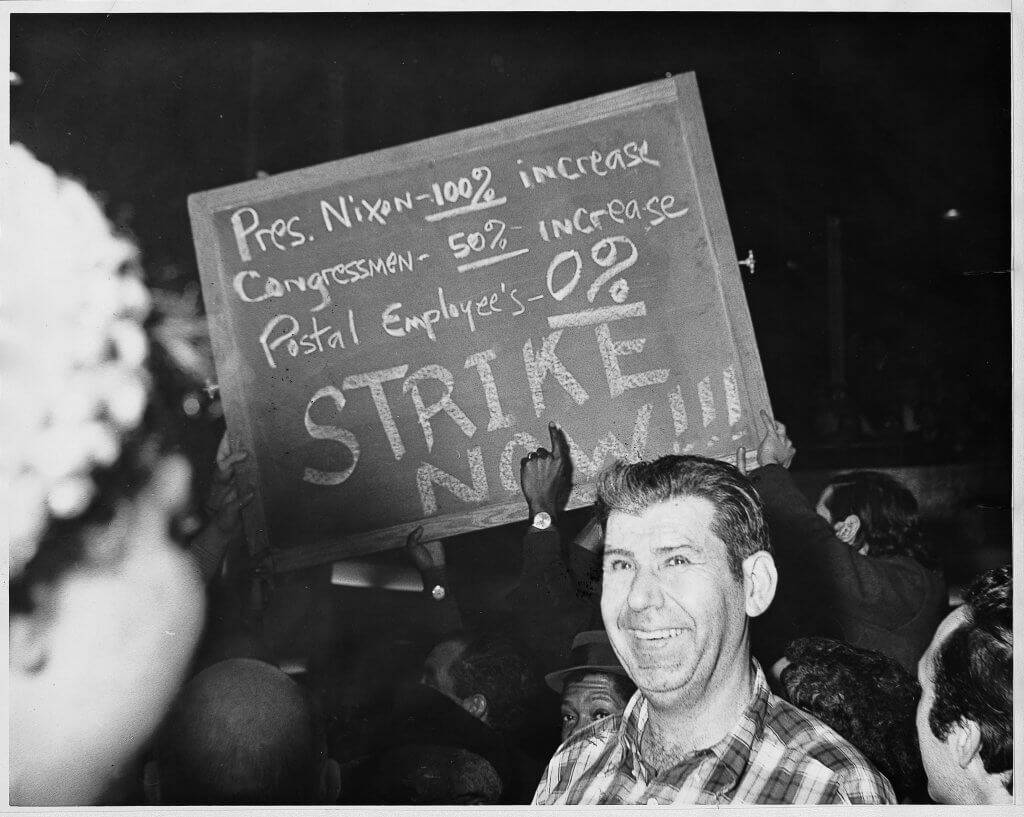

As Moe Biller, one of the strike leaders with the Manhattan-Bronx Postal Union, the largest local in the National Postal Union, or NPU, observed 25 years later: “Objective conditions were ripe.” During the 1960s many postal workers had effectively if unknowingly been preparing and practicing for this with their demonstrations in New York and DC over low pay. Postal union locals exist in every state and DC, and are part of large social networks. Starting with New York City’s Branch 36 of the National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC), workers struck as locals with either new leadership or their officers and stewards, in most cases against the opposition of national (the National Postal Union being an exception with their refusal to chastise membership). To call it a leaderless movement misses how much New York City strikers became a charismatic leadership to strikers in the rest of the country. They were the first ones out and the last ones back. They were role models, solidarity was high, and grievances were shared. It may have been a wildcat but it was disciplined and national. They also knew when to go back: they had shut down the nation’s mail and the Nixon administration was clamoring to negotiate after they went back.

Are there particular characters in your story that really stand out?

Lots of them. Every one of them, in fact. But Eleanor Bailey was still the most compelling interviewee. Eleanor had so many great stories, I could only tell a few in both my books about the post office, of being a thorn in the side of management with grievance filings and shop floor protests. She helped lead the 1970 strike as a distribution clerk working nights at the General Post Office in New York City. Eleanor was part of a wave of black women new hires in the 60s. She became active in the MBPU with Moe Biller and stayed active into her retirement until her death in 2018. There were four other New York City APWU (the successor to NPU) members that I interviewed in 2004, and you could see them deferring to her as so many must have in 1970 as a shop steward helping lead this rank-and-file wildcat strike. She also talked about her mentors in the union who provided continuity from past union struggles with postal management.

The Postal Service is in crisis right now. What does the history of the 1970 strike teach us about the crisis now?

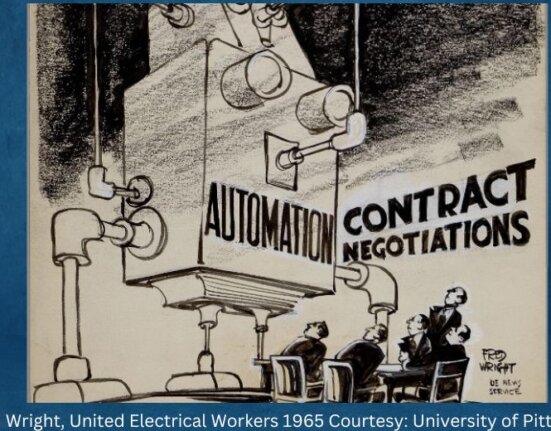

For nearly two centuries postal workers had two bosses: the post office and Congress, and for a nearly a century they had national unions that mostly functioned as lobbyists. The strike was a culmination of frustrations and rising expectations in rejecting this status quo. But it also clashed with some shared assumptions on Capitol Hill that postal reform needed to be based on a corporate structure. The strikers succeeded in forcing Nixon to the bargaining table and won a compromise that was not his postal corporation. But the compromise nevertheless produced the USPS hybrid agency/corporation. I’m sure there are some today from that time who can point and say, “I told you so.” How did anyone imagine the USPS would become totally self-supporting, provide universal service at reasonable rates, and provide consistently generous pay and benefits to employees (including no layoffs), either through negotiation or arbitration? This was not Milton Friedman’s neoliberalism. In fact, it’s tempting to call the USPS Richard Nixon’s experiment in a mixed economy. The USPS was still subject to congressional oversight, but without taxpayer subsidies. It was actually fine over the years as long as it could earn annual surpluses or come close to doing so by driving workers to higher productivity, automating some jobs while work-sharing and outsourcing others (what postal scholar Steve Hutkins calls “piecemeal privatization”), and generally enjoying continued volume growth with regular rate increases.

But privatizing forces turned the USPS into what Ruth Goldway, a former Postal Regulatory Commission chair, called a “cash cow” for the federal government because its revenue and obligations have been considered part of the unified federal budget. The worst milking—bleeding is perhaps a better metaphor here—was the 2006 Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act (PAEA) that manufactured an unnecessary financial crisis in 2009 that has now spilled over into today’s financial crisis as a result of huge revenue losses due to Covid-19. How did that happen? The Office of Personnel Management in 2002 discovered that the USPS had overpaid its CSRS annual pension contributions to the Treasury by about $71 billion (and was also being charged $27 billion for veteran’s pensions who were postal employees). Congress’s solution with the 2006 PAEA was to move the vets’ money back to the Treasury, but not return or lower the USPS’s pension obligations. Instead, they came up with the “mortgage plan from hell”: for ten years the USPS would have to pay about $5.5 billion a year into a Retiree Health Benefits Fund, when they, like other federal agencies, had done fine for years with “pay as you go.” This saddled the USPS with enormous debt when the Great Recession hit in 2008 and cut deeply into revenue every year. The USPS senior management began implementing austerity plans like cutting delivery days (failed), closing post offices and mail processing centers, and reducing hours—while at the same time slowing first-class mail despite technology that can speed it faster than ever. Meanwhile, under the Trump administration, the privatization narrative has strengthened. Even though Trump’s 2018 call for Congress to privatize the USPS was rejected, his refusal to issue a $10 billion USPS loan approved by the 2020 CARES Act or consider any “bailouts” to the USPS amounts to an attempt at starving the government agency into insolvency.

When I finished this book, the 2009 financial crisis was still an issue but Covid-19 was not. I concluded by predicting that some combination of grassroots labor and consumer activity along with political willpower would have to happen to resolve the ongoing crisis. Ominously, I concluded my previous book (There’s Always Work at the Post Office) in 2010 with the hope that future histories of the post office would be “chronicles and not epitaphs.”

This is your second book on the labor history of the post office, and you used to be a postal worker. How does your experience as a postal worker shape your scholarship?

I worked for 20½ years in Colorado and North Carolina, first as a distribution clerk for 9 months, then as a letter carrier after that. It gave me an inside look into the work and the work culture of the post office. It taught me how workers daily navigate a very authoritarian management structure while working together with management to move the mail. All of that helped me to know where to look in my research and oral history recording. I worked with some interesting, ambitious, and smart people, and heard so many different back-stories at the post office. For this book I borrowed an apt term from New York City NALC Branch 36 strike co-leader Tom Germano who later wrote his sociology doctoral dissertation on the strike: he called it “detached compassion.” Being personally and emotionally involved can be a distraction but can also be an entry point. I think people were willing to let me interview them who might have otherwise felt like I was an academic tourist. The post office has a byzantine structure and history that makes it difficult to comprehend. Yet I learned a lot more about the post office after leaving it and had to expand my vision from that of an employee. It’s a mixed bag. Part of me is still that dedicated but disgruntled postal worker who really wants to just serve people and not have to fight with management about overtime every day. It’s certainly possible to see postal work through workers’ eyes without having done the job, but it made it easier for me.

Now that you’re done with your book, what books are you looking forward to catching up on reading?

I finally got to finish David Blight’s brilliant biography of Frederick Douglass that my wife gave me for Christmas! And just in time for the pandemic lockdown, I have stockpiled what seem to be relevant contemporary reading: Masterless Men by Kerri Lee Merritt, Secession on Trial by Cynthia Nicoletti, and Rebels Against the Confederacy by Barton Myers. I’m also looking forward to reading recent books by Elizabeth Hinton and Kahlil Muhammad on the history of policing and white supremacy in America.