Our monthly series on new books in labor and working-class history continues with Jessica Ziparo’s new book, This Grand Experiment: When Women Entered the Federal Workforce in Civil War-Era Washington, D.C., which the University of North Carolina Press published in December. Ziparo earned her Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University, got a J.D. from Harvard Law School, and she currently lives in Seattle. She answered questions from Jacob Remes.

Your book is titled This Grand Experiment. If having women government workers was an experiment, was it a successful one?

Unsurprisingly, women proved to be capable, reliable, valuable workers. In 1859 there were only eighteen women listed in the Federal Register of Employees. In 1871, over a thousand women worked for the federal government and become a vital component of the federal workforce. In that sense, the “experiment” of employing women was a success. But it is of course much more complicated than that.

I took the term “this grand experiment” from an article Jane Swisshelm, newspaper editor and War Department clerk, wrote December 1865. As she knew then, the government’s “grand experiment” of employing women was deeply flawed at every level. Firstly, as Swisshelm explained, “There is a radical error in the manner of appointing women.” The nineteenth-century federal government was a patronage machine. Women were hired on the strength of their recommenders and carefully constructed narratives of dependence and woe. There were also allegations, not entirely untrue, that women were recommended and appointed because they were physically attractive or sexually available. Women who based their applications on their own skills and abilities were rarely successful. This meant that the women who the government hired were not necessarily the best candidates for the jobs and that some of the most qualified and ambitious were purposefully not hired. Then there was the manner in which women were regulated as employees and treated as colleagues. Women were paid half (or less) of what men were paid to perform the same or similar work. They had to do their ill-defined jobs with minimal training and had no hope of advancement, as the women’s pay was not only low but also flat.

Female federal employees were always seen as women—and commonly noble war widows or sexually available girls—before they were seen as employees. “Of the [male] clerks employed here, there is not one in twenty who can go into a room where women are employed, and transact business with one of them without in some way reminding her of her womanhood,” complained Swisshelm. Because women had no formal opportunities for training or advancement, and because supervisors, recommenders, and colleagues often cast women into objects of paternalistic pity and sexual desire, many female federal employees learned to present themselves as helpless and needy, and to use their interpersonal skills to keep themselves in the good graces of male supervisors to obtain and retain coveted jobs. These practices served to reify the government’s practice of treating women as lesser employees and gave credence to the stereotypes that female federal employees were either war widows to be pitied or sexually available women to be pursued or reviled. Some women did resist this construct, including those advocating for equal pay and advancements, and worked to dismantle this subordination, but as women lacked the power to mount a true fight against gender discrimination, and were dissuaded from collective action, this was not the watershed moment that it could have been.

How did having large numbers of working women change Washington as a city?

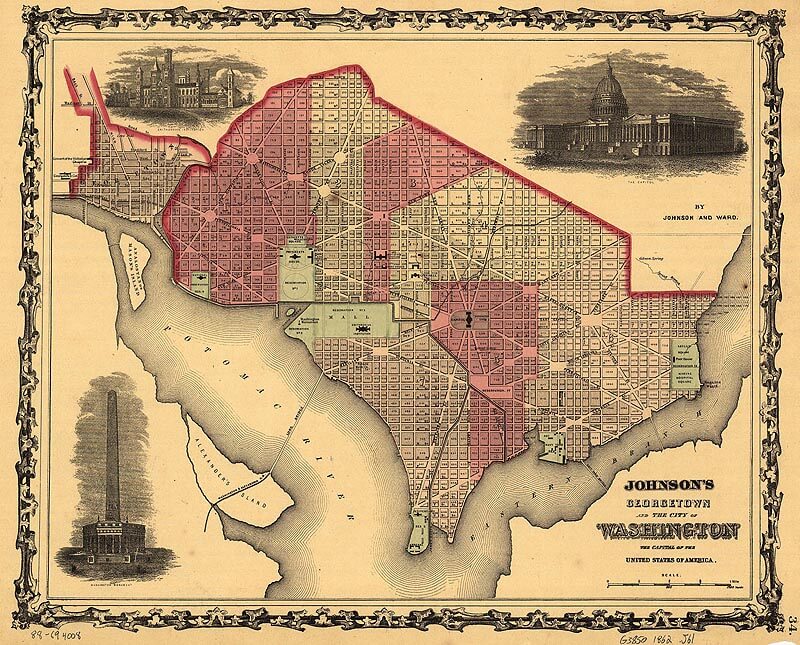

The City of Washington was changed most drastically by the Civil War and Reconstruction. Over the course of the 1860s, the sleepy, Southern town became a bustling, overcrowded, Northern city with a more racially diverse population. These changes were by far the most obvious and significant that the city experienced during this time. But I also believe that the presence of female federal employees and women applying to the civil service was also important.

Prior to the war, Washington, D.C., had been a masculine city.

Women changed that. A writer to the suffrage newspaper, The Revolution was amazed at the prevalence of women in the public buildings in Washington in 1870. She reported to newspaper that in her tour of public buildings, she found “[w]omen, women, everywhere women.” Many of the women the writer observed were likely female federal employees or applicants to federal positions. During the 1860s, suddenly female federal employees were visible all over the city of Washington—riding on omnibuses, walking in the streets, gathering in the galleries of Congress, shopping in the markets, chatting outside of boardinghouses, enjoying pleasure cruises, and assembling in meeting halls. Independent women came to Washington, D.C., to work, and life in the city amplified the freedom and liberty many of them felt. The more political and civic-minded female federal employees channeled this independence and freedom into philanthropic, political, and self-improvement activities throughout Washington, D.C. Other female employees, freed from the watchful eyes of parents, influenced by peers, and surrounded by strangers of the opposite sex, likely gravitated to and relished in the heterosexual social activities the city offered.

These unaccompanied women traversing the streets day and night and living and working among male strangers played a key role in transforming the masculine character of the nation’s capital to one more accepting of women’s presence and receptive to women’s wants and needs. Moreover, because it was the nation’s capital, women formed this new, conspicuous community of independent women in full view of the nation’s politicians and became a part of the struggle for women’s rights, whether they intended to or not.

There’s a lot of attention right now to public employees and their unions, not least because in Janus v. AFSCME, the Supreme Court is poised to cripple them. Does looking at women federal employees in and after the Civil War help us understand anything about public workers’ collective action?

As will come as no surprise to historians of labor: 1) the structure of female federal employment discouraged women from acting collectively; and 2) female federal employees were able to effectuate the greatest change when they did so.

Federal clerical jobs were among the highest paying, most exciting, and intellectually challenging jobs open to women of the 1860s. Women flooded federal departments with applications. Newspapers around the country reported on the crush of women applying to government jobs. For example, in 1866 an upstate New York newspaper informed its readers that the pressure women exerted to obtain federal positions was “overwhelming,” and described the Presidential Mansion, General Grant’s headquarters, and the Department of the Treasury as “besieged continually” by female applicants. An 1867 Baltimore Sun article described the quantity of women applying to federal positions as “innumerable.”

Because of this unrelenting crush of female applicants, and because the departments didn’t promote women (with limited exceptions) or spend appreciable resources training them, many supervisors and department heads saw women as fungible. For instance, in 1868 one Pennsylvania Congressman wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Treasury recommending two women for employment in the Treasury Department. He included a list of women employed in the department from Pennsylvania, on which he “indicated four names by underscoring them, two of whom might I think with propriety be displaced to make room for the above named friends.” It was every woman for herself as women actively worked throughout their federal employment to retain their positions. If a woman lost her position, she might suggest to a supervisor who might be removed from the payroll so that she could regain a place on it. Further dividing women, supervisors and male colleagues also discouraged women from participating in the women’s suffrage movement.

Despite this fierce competition, women did come together to act collectively and in doing so were able to effect change. Most importantly, between late 1864 and 1870, Congress received at least 740 female federal employee signatures on eleven separate petitions asking for greater pay. These petitions included an April 1866 petition signed by 59 female Treasury employees who asked that Congress consider “the vast disproportion existing between the salaries of the Male and Female clerks of this department” noting that the “labors and duties [of the men] are identical with our own and [their] home responsibilities in most instances are not so great.” The women asked: “If women can perform the same clerical duties as men, should not their salaries approximate in some degree to theirs”? Another petition was signed by 71 women in May 1870 who were “[e]mployed to scrubb and sweep the Halls stair ways + Rooms at the U. S. Treasury Building… most of us widows of soldiers who laid down thair lives in defence of glorious nation.” Many of these women were African American and almost two-thirds signed an X next to their printed names because they were illiterate. These 71 women asked Congress “to grant us more pay so that we can live with oure families without being compeled to beg as manny of us have to do to procure the necessary of life.”

Women’s collective pressure caused Congress to raise women’s salaries. Originally, the government paid women in clerical positions $600 per year (as compared to the $1,200 to $1,800 per year paid to male clerks). Women started to petition for greater pay in 1864. In January 1865, Congress raised women’s clerical salaries to $720 per year. Then in 1866, Congress again (at least partially) acknowledged the requests of female federal petitioners, fixing female clerical salaries at $900 per year. Women’s continued advocacy, in fact, almost caused Congress to pass a law making male and female clerk salaries equal—support for such a law was so great among the public and congressmen that newspapers reported it had been passed, and the congressmen themselves were confused as to how or why it hadn’t, since their votes should have secured its passage. That it came so close was in large part due to the brave collective action of hundreds of female federal employees.

When women started doing work that had previously been male, how did people’s ideas of that work change? Did people start seeing the work they did as specifically feminine?

Because women moved into so many places in the federal departments in the 1860s, and because the work at the time was largely undifferentiated, it’s hard to answer this definitively. I have a whole chapter on it! Government employment of women was a novel enterprise in the 1860s, and one that supervisors in the executive departments undertook with little forethought or planning. Not all supervisors chose to incorporate women into their workforce in the same ways and gendered notions of what women were, and were not, capable of limited women’s opportunities in government. A couple of examples can help demonstrate this complexity.

Women often performed labor in which men had been engaged, but many supervisors carved out the more monotonous tasks from men’s jobs and largely or exclusively assigned them to women. For instance, women in the Treasury Department developed expertise as investigators of mutilated currency—a discrete task pulled from the labor of male clerks and assigned to women. The Redemption Bureau employed women to identify notes that had been burned, buried, sunken, shredded, or otherwise damaged. These women received mutilated currency from across the country, and supervisors and the press praised their skills and professionalism. In 1870, the Redemption Bureau received “a small iron safe” full of charred and blackened currency from Nashville. A Washington, D.C. newspaper reported that the notes were so badly damaged “as to make it almost impossible to recognize to what denomination they belonged.” “The lady examiners” of the Bureau, however, were able to redeem the entire sum of $25,000. The article’s author lauded “[t]he wonderful expertness of the ladies in examining burnt money.” In 1893, a West Virginia newspaper reported that “the women detectors of burnt and counterfeit money are claimed to be the most expert in the world,” and private businesses employed Redemption Bureau women on their cases. Thus, while some supervisors assigned women mechanical and repetitious work—and thereby made this work “female”—women took limited jobs and managed to develop a new niche expertise.

While some jobs became “female” because supervisors parsed out specific work only to women, many female employees of the 1860s performed the same, or very similar, jobs as their male co-workers, albeit for half the pay. The Post Office Department, for instance, employed both men and women in the Dead Letter Office. When a piece of mail had insufficient postage, was improperly addressed, or for whatever reason was left unclaimed in post offices across America for a certain length of time, it was sent to the Dead Letter Office in Washington. Male and female clerks labored together (although separated physically in the same space) using a combination of experience, teamwork, and detective skills to redirect such mail, the quantity of which was enormous. Although men and women performed identical intellectual labor in the Dead Letter Office, however, men were the only employees allowed to initially open the mail, lest it contain something “scandalous” and men were paid significantly more to do the work. In this instance, however, redirecting dead letters did not become “female” work during this period.

No matter her position, however, a female ![]() federal employee’s gender was the characteristic by which she was identified and evaluated. Supervisors across departments used gendered language to set women apart from their male colleagues. In the 1867 Federal Register (a register of many, but not all, federal employees), 163 women worked under the job title “Ladies” in the Treasury Department, which offers no indication of what they actually did. That year, the Treasury Department also employed women as “copyists,” “copyists and counters,” and “female clerks.” During the Civil War era, all women were, with very limited exceptions, labeled as “Mrs.” or “Miss” in the Federal Register. Although men also performed copy work as part of their jobs, supervisors never described men as “copyists,” nor did they designate them as “Gentlemen” or “Mr.” Women’s job titles were misleading as they purported to, but did not, differentiate what women did vis-à-vis men and vis-à-vis other women. In debates over female pay at the end of the decade, congressmen readily admitted that some men and women performed precisely the same jobs despite the men’s job title of “clerk” and the women’s job title of “copyist.” Appending “female” or “copyist” to the job title narrowly circumscribed women’s roles, options, and futures in the federal workforce but not in all instances during this period did it make the work “feminine.”

federal employee’s gender was the characteristic by which she was identified and evaluated. Supervisors across departments used gendered language to set women apart from their male colleagues. In the 1867 Federal Register (a register of many, but not all, federal employees), 163 women worked under the job title “Ladies” in the Treasury Department, which offers no indication of what they actually did. That year, the Treasury Department also employed women as “copyists,” “copyists and counters,” and “female clerks.” During the Civil War era, all women were, with very limited exceptions, labeled as “Mrs.” or “Miss” in the Federal Register. Although men also performed copy work as part of their jobs, supervisors never described men as “copyists,” nor did they designate them as “Gentlemen” or “Mr.” Women’s job titles were misleading as they purported to, but did not, differentiate what women did vis-à-vis men and vis-à-vis other women. In debates over female pay at the end of the decade, congressmen readily admitted that some men and women performed precisely the same jobs despite the men’s job title of “clerk” and the women’s job title of “copyist.” Appending “female” or “copyist” to the job title narrowly circumscribed women’s roles, options, and futures in the federal workforce but not in all instances during this period did it make the work “feminine.”

Now that you’re done with your book, what books are you looking forward to catching up on next?

As the mother of a truck-obsessed toddler, I mainly read books about construction, emergency, and sanitation vehicles, changing pronouns on the fly (in a shocking coincidence, nearly all anthropomorphized vehicles are male!). There are, however, a number of grown-up books I’m looking forward to reading. Kate Masur just worked to have John E. Washington’s They Knew Lincoln republished and I’m looking forward to re-reading it and Masur’s introduction, which details Washington’s life and provides context to the book’s initial publication. I also look forward to reading Judith Giesberg’s new book Sex and the Civil War: Soldiers, Pornography, and the Making of American Morality, which I wish had come out prior to This Grand Experiment so that I could have benefited from its use as a source. Finally, I’m looking forward to reading all kinds of fiction. Remember fiction, historians with book projects?