Ohio’s open carry law has generated a considerable amount of controversy given that Cleveland is hosting this year’s Republican Convention. In light of recent killings in Louisiana, Minnesota and Texas, critics, both liberals and staunch advocates of “law and order”, have raised serious questions about the law, and the city’s cop union, those responsible for defending the local ruling class, have called for a temporary suspension of it after learning that some black activists will be armed.

This is hardly the first time the issue of firearms has led to acrimonious debate and discussion in this Lake Erie City. In fact, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, numerous strikebreakers and managers carried guns during industrial disputes, insisting that the weapons were necessary to protect the property rights of capitalists and the mobility of anti-union workers. The legal system in Cleveland, like most other places, largely protected the brutal actions of scabs and bosses. In many cases, protecting scabs’ right to work also meant defending their right to shoot.

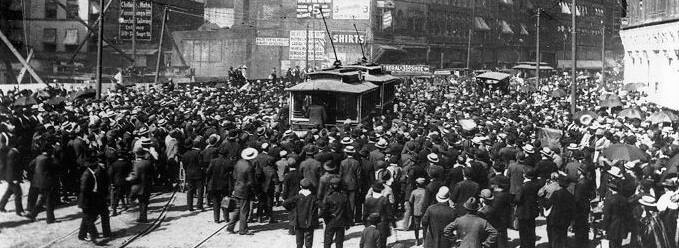

Consider some early history. One of the most dramatic disputes in the city was the 1899 strike against the Cleveland Electric Railway Company’s Big Consolidated Line. Fought mostly over wages and union recognition, the roughly 850 strikers enjoyed much community support during this conflict. Daily demonstrations, sometimes involving over 8,000 protestors, had routinely succeeded in preventing scabs from crossing picket-lines. They were not entirely successful, but militancy and solidarity, in many instances, worked. In the face of the violence, including the dynamiting of railway cars, authorities brought in state troopers, and a number of non-unionists armed themselves for protection. Both sides were guilty of violence, though some of the worst bombings, according to historian Stephen Norwood, were likely caused by agent provocateurs. And as strike historian John Stark Bellamy has written, “not a single instance of dynamiting had ever been or ever would be traced by to the union or its card-carrying members.” In one of the dramatic moments of the strike, a non-union conductor named Ralph P. Hawley fatally shot an eighteen-year-old protestor named Michael Connzweit. Represented by anti-union lawyer Jay P. Dawley, the jury acquitted Hawley, concluding that he had acted out of self-defense.

Most middle class and elite observers, both outsiders and Clevelanders, criticized labor violence, but said little about the thuggery generated by police, state troops or strikebreakers. Several Catholic and Protestant leaders, business owners, and public officials, denounced instances of working class militancy, called for order, and insisted that workers respect the rights of non-unionists. Confederate veteran, former Klan leader, and Huntsville, Alabama-based commercial real estate investor, N. F. Thompson, visited Cleveland at the time and later expressed shock by the life-threatening mayhem. Speaking about the event to a room full of anti-union businessmen in New York City in 1904, Thompson recalled that his “southern blood was beginning to get up” due to the “inhuman” activities.

Almost exactly a year after witnessing Cleveland’s streetcar strike, Thompson gained national attention for speaking before the US Industrial Commission, where he warned that labor unions consisted “the greatest menace to this Government that exists inside or outside the pale of our National domain. Their influence for the disruption and disorganization of society is far more dangerous to the perpetuation of our Government in its purity and power than would be the hostile array on our borders of the armies of the entire world combined.” Thompson called for a number of responses, including a “justifiable homicide” law, which would protect the rights of individuals responsible for “any killing that occurred in defense of any lawful occupation.” In other words, the former Klansman put forward a proposal that resembles what we know today as the “stand your ground law.” The Cleveland streetcar strike was one of numerous disputes that Thompson had studied before he put forward this attention-grabbing proposal. For him and others in anti-union circles, managers and anti-unionists like Ralph P. Hawley must enjoy the right to work as well as the right to shoot.

It is entirely possible that John A. Penton, owner of the Cleveland-based Penton Publishing Company, former organizer for the anti-union National Founders’ Association and Thompson’s colleague in the open-shop movement, had Thompson’s idea in mind in 1906 when he armed dozens of his non-union workers during a dispute at his shop. “We have issued an injunction that’s made of lead and can’t be modified,” he explained to a journalist. Penton, who also carried a revolver, bragged that “Our employees are instructed to shoot any man who even jostles them; to shoot at once and right. The Company will stand behind them.”

No deaths resulted from this action, but one of Penton’s colleagues, Israel Whitworth, nearly killed Eli Black, a striker, by driving a chisel into his back. This came at the end of the strike, which resulted in a victory for Penton and his gunmen. Yet authorities arrested Whitworth for attempted murder. This was just a minor inconvenience: at trial, Whitworth was successfully defended by the veteran union-busting attorney and president of the Cleveland Employers’ Association, Jay P. Dawley. Penton, his scabs, and Whitworth faced no meaningful consequences for their actions.

Labor unionists in Cleveland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, like black lives matter activists today, had little faith in the legal system or in the most vocal defenders of gun rights. After all, their opponents in the open-shop movement, inspired by N. F. Thompson’s message promoting justifiable homicide, demonstrated that union lives didn’t matter in elite circles. The friends, relatives, and union brothers and sisters of Michael Connzweit and Eli Black knew this painfully well. Today, the friends and family members of Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old killed by Cleveland’s police, and countless advocates of social justice, understand this painful reality as well.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.