This essay is the third contribution to our symposium on Tom Alter’s new book, Toward a Cooperative Commonwealth: The Transplanted Roots of Farmer-Labor Radicalism in Texas, published recently by University of Illinois Press. We started with Kyle Wilkison’s analysis of the book’s contribution and survey of previous literature. Then Theresa Case weighed in with a tour of the book and some questions. Now Chad Pearson suggest that Alter’s book counters helps to re-frame old arguments. Next we will welcome a response by Tom Alter. Thanks to Chad Pearson for organizing this symposium. These are peer-reviewed.

Tom Alter’s thoroughly researched and well-written new book helps us to appreciate the class-based radicalism that far too many of today’s historians have ignored. The stories he uncovers, told partially through the lens of members of the extraordinary Meitzen family, return us to the dramatic class-struggles launched by populists and socialists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I want to highlight the way Alter describes farmers’ movements over the course of decades. This framing distinguishes his approach from others who have written about the same and similar movements in recent years. I will demonstrate that Alter’s book is a refreshing challenge to those who have downplayed the radicalism of farmer-activism and insisted that we remember agrarian activists as pro-capitalist reformers. The evidence Alter has provided reveals that his subjects found capitalism, rather than industrial bigness, as the source of their misery and the main barrier to progress. In making his case, Alter takes seriously the very best leftist historiographical traditions, which acknowledge the exploitative and oppressive dimensions of capitalism as well as the meaningfulness of oppositional movements from below.

First, a few remarks about the scholarship about farmers’ movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For many decades, historians have debated how we should interpret those active in these mostly southern and western-based movements. Were these people backward thinking Jeffersonian romanticizers and simpletons or forward-looking cosmopolitan modernizer?[1]

A far more interesting debate, in my mind, concerns the nature of their politics. For decades, a cohort of left-leaning scholars have insisted that Populists were genuine radicals inspired by a producerist ideology—that is, those who did the work were entitled to the fruits of their labor. Norman Pollock, writing in 1962, declared that Populism shared common features with Marxism. In his words, “Each pointed to the same economic features as defining capitalism.”[2] And while plenty of organized farmers’ lashed-out most enthusiastically against the big capitalists like the Jay Gould’s and Andrew Carnegie’s of society, plenty of others, in Pollock’s words, took aim at “the economic system itself.”[3] In his pathbreaking 1978 book about agrarian movements in the Southwest, the late James Green referred to Texas Populists as “militant antimonopolisits” who collaborated with socialists.[4] In that year, Lawrence Goodwin maintained that they were “concerned with certain forms of capitalist exploitation.”[5] Most agreed that the massive corporations constituted capitalism’s most imposing and dreadful examples. The reasons are clear: big business out-competed small businesses, ripped off consumers, and exploited workers.

Yet the interpretation that farmer-activists were radicals, militants, or even softcore socialists has come under sustained attack over the past three decades or so. Sizable numbers of today’s historians of farmers and workers’ movements, seeking to distance themselves from New Left interpretations, have insisted that these people were progressive liberals who opposed a particular type of capitalism, but did not take direct aim at the system itself. They were, in short, reformers not revolutionaries. Charles Postel is most famously associated with this perspective, declaring that the Populists sought to build “an alternative capitalism in which private enterprise coalesced with both cooperative and state-based economies.”[6] More recently, Gregg Cantrell has claimed that Texas’s populists’ advocated “socially responsible capitalism.”[7] Writing about farmers in the Nonpartisan League in a later period, Michael Lansing has maintained that his subjects consisted of “lower-middle class” activists not laborers, and that they were “thoroughly committed to capitalism and deeply respected private property.”[8]

These interpretations are compatible with Lizabeth Cohen’s study of the rebellious workers who built the CIO in Chicago; in her telling, workers wanted “moral capitalism.”[9] And even some businessmen have added their voices to this question. In 2013, the former CEO of Whole Foods, John Mackey, wrote a gripping book titled “Conscious Capitalism.”[10]

This brings us to Alter’s study, which presents capitalism as the core source of considerable unhappiness for activists in Texas and outside its borders. Alter does not generalize about all participants in farmers movements, but instead focuses primarily on the Meitzens and the many down-and-out Texans they helped to inspire and organize. At the same time, Alter never loses sight of larger developments in Texas and beyond, including south of the border and in Germany, Ireland, and Russia. Most importantly, Alter, unlike many others, draws sharp class distinctions, offering especially enlightening descriptions of the plights of outraged tenant farmers. His subjects drew radical, rather than liberal, lessons from the exploitation, oppression, and political corruption they encountered locally, and they found encouragement from the struggles they learned about outside Texas. Devasted by poor economic conditions, growing numbers became radicalized in the late nineteenth century, painfully recognizing the permanency of capitalism’s cruelty. As Alter puts it, struggling farmers in the mid-1880s “no longer viewed the economic crisis as temporary” (69). In his telling, they were class conscious combatants rather than patriotic antimonopoly reformers.

This meant fighting for a fundamentally better system for farmers and workers on class lines. Consider their actions in support of labor activists in the mid-1880s, when thousands of Knights of Labor (KOL) members challenged the obscenely wealthy Jay Gould during a series of railroad strikes. Texan activists, including E. O. Meitzen–who held membership in both the Farmers’ Alliance and the KOL—eagerly backed the confrontational strikers. Victory against Gould in 1885 emboldened thousands, leading to a massive KOL membership increase and heightened awareness of the ruling class’s ruthlessness. That strike victory was followed by a crushing defeat the next year, when National Guardsmen, Pinkertons, and businessmen-organized Law and Order Leagues intimidated strikers, escorted scabs across picket-lines, and blacklisted its leaders, including Martin Irons, who eventually landed in central Texas. Yet farmer-activists in Texas learned valuable lessons from this emotionally distressing and often physically painful experience.

Alter, reinforcing the insights of historian Matthew Hild, points out that “The movement culture of the Farmers’ Alliance in many ways grew out of the support shown by its members of striking railroad workers against Gould’s system again in 1886” (69).[11] This coalition was critical for several reasons, including the role farmer-labor activists played in the electoral victory of H. S. Broiles to the position of Fort Worth mayor; he held membership in both the Farmers’ Alliance and the Knights of Labor.

Together, the coalition of labor and farmer activists learned much from their confrontations in the mid-1880s. Importantly, oligarchs like Gould and the other captains of industry were hardly their only opponents. To properly understand the repressive dimensions of the 1886 strikebreaking clampdowns, we must explore the role of vigilantes active in Law and Order Leagues. Sadly, historians have given them less attention than other strike opponents. These powerful, secretive, and threatening organizations, consisting of local bankers, merchants, and newspaper editors, emerged in both modest sized communities like Sedalia, Missouri and Parsons, Kansas as well as in cities like St. Louis. Their memberships, comprising reactionary, as opposed to “radical,” members of the middle class, armed themselves as they protected scabs and forcibly expelled union activists from communities. The founder of this movement, newspaper owner J. West Goodwin of Sedalia, took credit for helping to break the strike in Missouri. Writing in in 1889, Goodwin declared that the Law and Order League “was the most important factor in” crushing the uprising.[12] Such comments were obviously self-serving and probably overstated, but Goodwin was nevertheless a thorn in the side of KOL members, including Martin Irons.

Martin Irons suffered from a blacklist promoted by capitalists representing different-sized workplaces. We can assume that these folks considered themselves moral, upstanding citizens in their communities. I’m sure many attended church, gave to various charities, and were kind to animals. Yet they nevertheless banded together to hurt Irons and other working-class combatants.

After the strike’s collapse, Irons spent years trying to secure employment from various-sized businesses throughout the Southwest. “Whenever Martin Irons applied for work,” a newspaper reported in 1888, “he was driven away.”[13] The famous drifter eventually landed in Texas, where he collaborated with old-time populist G. B. Harris in helping to organize tenant farmers before he died in 1900.

Let’s ask the question: Do honest researchers think Irons, a self-identified socialist and member of the Grange, had experience with, or wanted to build, something called “moral capitalism” or “socially responsible capitalism?” Seems unlikely, since the labor leader had been repeatedly hounded by belligerent middle-class business owners throughout parts of the Midwest and Southwest. Does it seem reasonable to assume that his comrades aspired to be like the thousands of Law-and-Order Leagues members? I doubt it.

While the virtually penniless Irons desperately sought stable employment, the Meitzens continued to organize. Their radicalism, Alter writes, continued into the 1890s, when E. O. made the rational decision to split from the Democratic Party and become a “Populist insurgent” (75). He and his colleagues supported the “cooperative plan,” which, in Meitzen’s words, was designed help the ordinary farmer cope with the “financial pressure, with which he is struggling more and more every year” (76). Yet experimentation with the exchange demonstrated the limitations of working within the system. As Alter put it, “a cooperative venture within a corporate capitalist system failed to alleviate the dire plight of southern farmers” (78). And that is the class Meitzen organized. As a committed movement builder, he devoted considerable amounts of time to different regions of Texas, where he spoke to hundreds of urban and rural laborers. In the process, he collaborated with leaders like Thomas Nugent, whom Alter, echoing historian Kyle Wilkison, calls “a Christian socialist” (87).[14]

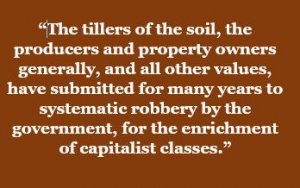

In Alter’s telling, the Farmers’ Alliance delegates who gathered were hardly pro-capitalist champions. Consider a meeting in Dallas in November 1891. Here they made statements that drew zero distinctions between different types of capitalists or bosses: “The tillers of the soil, the producers and property owners generally, and all other values, have submitted for many years to systematic robbery by the government, for the enrichment of capitalist classes.” The statement concluded that the delegates, seeking to advance the general interests of “the great mass of laborers and producers,” promised to act “without taking the advice of some boss” (85). These delegates did not qualify what they meant by the “capitalist classes,” but we know that they left the meeting energized, determined to organize independently of “bosses.” We might assume that they had the corporate titans in mind, since virtually all harbored a healthy disgust for the nation’s repulsive robber barons, but we can also be confident that that many likely held similar antagonistic feelings for members of local Chambers of Commerce, which included bankers, small business owners, and the deeply exploitative credit merchants. Did indebted farmers to credit merchants think, “well, at least the big capitalists aren’t ripping me off?” Or how about the workers scraping by in modest-sized proprietary workshops. Did they somehow believe, “while my boss might be an exploitative jerk, at least he doesn’t occupy the same class position as Jay Gould?” Probably not.

Metizen and his comrades continued to draw clear class lines by supporting labor activists during dramatic confrontations, including in 1894. That year’s extraordinary railroad strike offered another painful lesson about the role of capitalists and the political system that backed them. The aftermath of that dispute led to additional coalition-building movements between urban and rural laborers. At the state meeting in Waco, delegates, consisting of both whites and Blacks, adopted resolutions calling for far-reaching reforms, including government ownership of major industries such as railroads and telegraph service (92). It is difficult to identify any kind of thirst for capitalism here.

Later in the decade, radical-oriented farmers, many of whom began reading the socialist newspaper, Appeal To Reason, faced an increasingly aggressive Democratic Party determined to dilute, and ultimately coopt, the movement. “The Democratic Party,” Alter writes, “crushed the Populist movement and became the party of Jim Crow.” It was responsible for cause enormous amounts of harm to those who sought to build a durable opposition to society’s rulers. Alter continues, “In response to the biracial Populist revolt, Jim Crow legislation swept the South in the years to follow, ushering in an era of terrorism against African Americans. The beginnings of political unity between poor black and white farmers forged by Populists was now shattered” (103). Populism, as an independent force, was largely dead. But Democratic Party dirty tricks and the triumph of the so-called “great merger movement” did not mark the end of Texas radicalism. Alter writes, “Attempts to maintain the Populist movement after 1896 proved to be a death rattle but did produce the birthing pains of a socialist movement” (106).

Transitioning from populism to socialism made logical sense to many, and Alter credits what he calls the “preexisting network of farmer-labor activists” for its emergence. Of course, some veteran activists joined the Democrats but, as Alter explains, “Many rank-and-file farmer-labor militants opposed a relationship with the Democratic Party” (108). And these people showed a sustained appetite to battle the profoundly unfair economic system itself. E.R. Meitzen was clear about the nature of class inequality, pointing fingers at “the man who lives and thrives off the labor of others rather than by the sweat of his own face” (109). Here we see consistency with the unambiguous anti-capitalist position organized farmers took in Dallas in 1891.

By this time, labor radicals, with memories that stretched back decades, had a clear understanding of their adversaries, including small and medium sized business leaders who held membership in anti-labor open-shop associations. Indeed, modest-sized business owners were particularly hostile to workers who sought to build unions, organize boycotts, stage strikes, and promote socialism. “Most scholars would agree,” historian Larry Gerber maintained in 1997, “that small firms” were “more vehement in their opposition to unions than the corporate giants of the economy.” To be fair, not all historians agree that the small business were the key leaders of the union-busting open-shop campaigns; plenty of large ones participated, too.[15] As a reporter for the New York Times explained in 1904, “the open shop is the first issue ever presented to employers upon which they could combine in entire agreement.”[16]

Few scholars of farmer-labor movements have examined the far-reaching impact of the open-shop movement. This is unfortunate, since we see them in Texas. Some of the old opponents of groups like Knights of Labor, including J. West Goodwin, continued to build union-busting organizations and terrorize workers. The modest-sized printshop and newspaper owner helped launch numerous so-called Citizen’s Alliances throughout much of the nation, including in Texas. Activists involved in these populist-sounding organizations brutalized labor militants and socialists under the banner of protecting “the common people.” So, did farmer activists who supposedly imagined a virtuous capitalism want to join with these people? I doubt it.

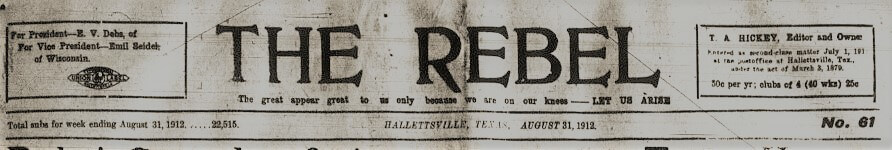

The leftist activists Alter has written about had little in common with most business owners. After all, sizable numbers of the farmers who joined the socialists were radicals, and Alter bluntly states that “the dominant ideological strain in the socialist movement, even its agrarian wing, was Marxist” (109). He offers fascinating insights into the characteristics of the Texas Socialist Party, which emerged as a statewide organization in 1904. Socialists in Texas, led by talented organizers like the Irish-born Thomas Hickey, fought battles locally and demonstrated solidarity with movements outside of the country. Members, for example, called for social ownership and democratic control of the means of production and distribution, and demanded that the US military stay out of Mexico, offering what Alter calls “an early model of working-class internationalism and anti-imperialism for others to draw on when war in Europe began” (152).

While the Texas Socialist Party was numerically far smaller than the Texas’s Populists in the late nineteenth century, its more than 4,000 members on the eve of the First World War alarmed their class enemies. Their opponents, based in Texas and nationally, were numerous, which made organizing enormously risky. The federal government coordinated much of the repression, and Alter believes that the era’s onslaught was unprecedented, writing that “never had the government engaged in anything as wide-ranging as during the Red Scare of 1917-21” (172). The Meitzens and their comrades had no illusions that the US entered the First World War to make the world “safe for democracy.”

In this context, E. R. Meitzen and some of his colleagues became active in the Nonpartisan League (NPL), which emerged as a significant political force in North Dakota before expanding to other largely agricultural states, including Texas. E. R., believing that the NPL offered emancipatory promises to the nation’s toilers, referred to it as “the most revolutionary movement for workers America has ever seen” (180). E. R.’s analysis seems entirely incompatible with how Michael J. Lansing described the organization.

Yet Alter and Lansing have taught us much about the figures in the NPL as well as its most violent opponents. Consider a case involving an anti-NPL mob in Mineola, an east Texas community in April 1918. The mob here, inspired by the words of Minster Charles V. Hughes who denounced the organization for supposedly spreading German propaganda, physically beat four NPL organizers. The terrorism continued, and Alter treats us to attention-grabbing tales of regional ruling class thuggery. Fascinatingly, one organizer, M. M. Offut, attempted to reason with Hughes by insisting that the organization consisted of law-abiding folks with no ties to Germany. Alter explains what happened next: “a group of ruffians grabbed him. With a pair of sheep sheers, they hacked off his long gray beard and hair after they kicked and beat him.” Finally, the men forced him on a train, demanding that he never return (187).

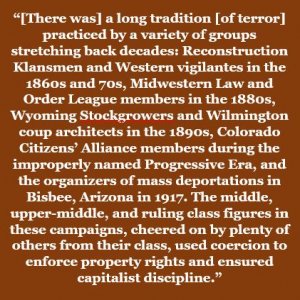

Importantly, the men responsible for this gruesome attack and drive-out action were not members of the corporate elite. Yet this example of local bourgeois thuggery should be familiar to us, since it followed a long tradition practiced by a variety of groups stretching back decades: Reconstruction Klansmen and Western vigilantes in the 1860s and 70s, Midwestern Law and Order League members in the 1880s, Wyoming Stockgrowers and Wilmington coup architects in the 1890s, Colorado Citizens’ Alliance members during the improperly named Progressive Era, and the organizers of mass deportations in Bisbee, Arizona in 1917. The middle, upper-middle, and ruling class figures in these campaigns, cheered on by plenty of others from their class, used coercion to enforce property rights and ensured capitalist discipline.

Let me conclude by repeating my appreciation for Alter’s contribution. As a student of different forms of business-generated anti-union terrorism, I found his commitment to placing class struggles at the center of his analysis welcoming, particular in a scholarly environment that remains hostile to Marxist interpretations of the past. This partially means recognizing the truly exploitative and repressive dimensions of capitalism while resisting calls to sanitize it. Alter and his subjects showed a better understanding of the stakes involved in these struggles than many of today’s wishful-thinking liberal historians. At the turn of the century, E. O. Meitzen and his comrades had come to, as Alter explains “the same conclusions as Marx and Engels”: “the need for workers and farmers to have their own revolutionary party” (21).

[1] For the view that they were backward-looking, see John D. Hicks, The Populist Revolt (Minneapolis, 1931). Norman Pollack has suggested that they embraced modern methods of farming. Norman Pollack, The Populist Response to Industrial America: Midwestern Political Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962).

[2] Pollack, The Populist Response, 72.

[3] Ibid., 82.

[4] James R. Green, Grass-Roots Socialism: Radical Movements in the Southwest,1895-1943 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978), 8-9.

[5] Lawrence Goodwin, The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), xxi.

[6] Charles Postel, The Populist Vision (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[7] Gregg Cantrell, The People’s Revolt: Texas Populists and the Roots of American Liberalism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 117.

[8] Michael J. Lansing, Insurgent Democracy: The NonPartisan League in North American Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 22.

[9] Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 286. Democratic Party cheerleader Michael Kazin has reintroduced the idea of “moral capitalism” in a favorable light. Reviewer Eric London, showing no tolerance for such nonsense, notes that “Kazin never explains precisely how Democrats have made capitalism work ‘morally’ for both capitalists and workers, an explanation that would be akin to trying to explain how one might make slavery ‘right’ for both slave and owner, or feudalism equally beneficial to both lord and serf.” Eric London, “An unoriginal hagiography of the Democratic Party: Michael Kazin’s What it Took to Win,” World Socialist Web Site, https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2022/03/16/kazi-m16.html

[10] John Mackey and Rajendra Sisodia, Conscious Capitalism: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business (Cambridge: Harvard Business Review Press, 2013).

[11] Matthew Hild, Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007), 74.

[12] The Sedalia Weekly Bazoo, October 1, 1889, 2.

[13] “Martin Irons,” Alexandria Gazette, May 7, 1888, 1.

[14] Kyle G. Wilkison, Yeomen, Sharecroppers, and Socialists: Plain Folk Protest in Texas, 1870-1914 (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2008), 168.

[15] Larry G. Gerber, “Shifting Perspectives on American Exceptionalism: Recent Literature on American Labor Relations and Labor Politics,” Journal of American Studies 31 (August 1997): 270. Also, see Howell John Harris, Bloodless Victories: The Rise and Fall of the Open Shop in the Philadelphia Metal Trades, 1890-1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). Not all share this view. Andrew W. Cohen, The Racketeer’s Progress: Chicago and the Struggle for the Modern American Economy, 1900-1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 52. Robert D. Johnston, The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 67-80; Jeffrey Haydu, Citizen Employers: Business Communities and Labor in Cincinnati and San Francisco, 1870-1916 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008).

[16] “The Open Shop Movement,” New York Times April 29, 1904, 8. Also, see George E. Barnett, “The Printers: A Study in American Trade Unionism,” American Economic Association Quarterly 10 (October 1909): 342-345.