This is the fourth in a series of essays on “Higher Ed Wall-to Wall in Tennessee,” which will continue for the rest of this week. This series of posts highlights voices and union-led campaigns on higher-ed campuses across Tennessee. We hope to offer both a picture of the challenges that we face and perhaps some organizing solutions, particularly to other higher education employees in right-to-work states, to help navigate the shifting academic terrain that we are experiencing in the face of COVID-19.By Anonymous ( The author of this post did not feel comfortable including their name because they are not a tenured faculty member and feared potential retribution.)

Since the COVID-19 outbreak first shut down wide swaths of the US economy in early March, the previously unrecognized figure of the “essential worker” has loomed ever larger. Those first weeks and months, during which many people found themselves either working from home or not working at all, saw a select number of jobs deemed “essential”—meaning that those who performed those duties were not afforded the chance to opt out of returning to work. On university campuses, as has been true elsewhere, those obligated to continue with their normal duties were most often those with the lowest salaries and, within the context of a global pandemic, the most potentially dangerous jobs (insofar as they risk exposure to the virus): maintenance and housing workers, cleaning personnel, and administrative staff all fall into this category. In many cases, these employees returned to their offices and worksites without proper personal protective equipment (PPE), and facing uncertain and even contradictory instructions from upper administration.

This post draws on formal interviews and informal conversations with essential workers at universities and colleges from across Tennessee. It synthesizes the concerns and fears that workers expressed, and closes by offering a possible solution as we move forward in these uncertain times. Within the context of the series of posts about higher education workers in Tennessee, it was considerably more difficult to find essential workers willing to go on record to discuss these issues. To protect the identities of those who participated, either formally or informally, all names and identifying information have been changed and/or removed. Home institutions/places of employment have been left in, where appropriate.

What became clear in these conversations is that there has been little effort to implement a statewide system for supporting and protecting essential workers on campus. Some respondents, including one housing worker at Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU) with more than twenty years at their current position, explained that the last few months have not been especially difficult, and that their day-to-day responsibilities remained mostly the same as before the pandemic. Others, including a member of the cleaning staff at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga (UTC), noted that they’ve seen their hours cut back to two days per week, and that there is little certainty or reassurance from higher ups about what the future will hold.

One key area of concern relates to the provision—or non-provision—of PPE and the uneven enforcement of safety guidelines on campus. One worker reported that over the past four months, their campus administration has not held contract and outside workers accountable to the same extent as university employees. Contractors on short-term jobs have been allowed to work on campus without masks, putting the health of others at risk. Maintenance and custodial staff also voiced their frustration at the lack of clear messaging about how the impending reopening of campuses across the state will work and what, if any, contingency plans are being considered.

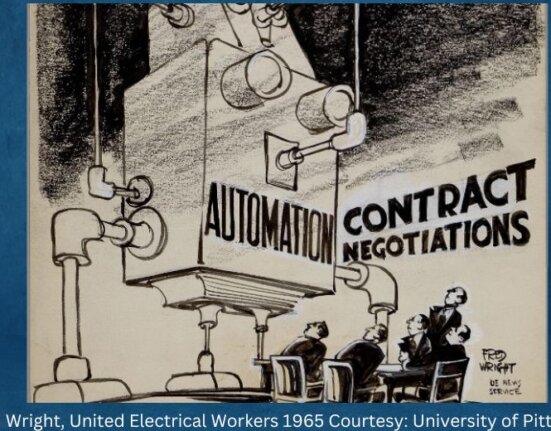

With public universities facing the possibility of severe budget cuts, fears about downsizing and outsourcing appeared in different contexts, but once again depended on the local specificities. MTSU, for example, has stated that they will not participate in a statewide program to use contract labor for maintenance and facilities work. Essential workers noted this public commitment as a factor in their broader feelings of “contentment” at present. At other campuses, the situation is less clear. UTC and UTK have battled against outsourcing at various points over the past two decades, including winning a major victory in 2017, as UCW helped defeat the efforts of then-Governor Bill Haslam to outsource the UT system’s facilities and maintenance positions. This victory protected hundreds of jobs across all four UT campuses. However, in the current economic climate, these ideas are beginning to circulate once more, as workers in housing and maintenance have spoken up about rumors concerning possible outsourcing due to supposed financial constraints. In moments of crisis, it has become commonplace to try to cut costs by shedding salaries and, through privatization and outsourcing, benefits costs for employees, especially those at the lower ends of the pay scale. Respondents expressed frustration at the unequal distribution of sacrifice that this implies, and voiced their hopes that “any further reductions start at the top of the university system,” rather than impacting those who are already most precarious.

Higher education across the country, including in Tennessee, faced serious challenges before the COVID-19 outbreak. For decades, public college and university administrations have watched as tax cuts have whittled away the financial support that once came from the government, and have been complicit in shifting that burden onto students, both directly through tuition increases and indirectly via the privatization of entire sectors of the higher education system. The pandemic has dramatically exposed the instability and inequality at the heart of our current situation, and, to borrow the language of those upper administrators who have happily sent maintenance, custodial, and clerical staff back to campus over the past four months, it is essential that we, as higher education employees, fight to make sure that the economic and health burdens of this crisis do not fall primarily on those who can afford them the least. UCW of Tennessee stands with essential workers and calls for any future financial cuts and adjustments to start at the top, rather than the bottom, and demands that the UT system protect its employees rather than treating them as disposable. Only then can we begin to construct a better, more equitable University of Tennessee for everyone.