Our series of interviews with author of new books in labor and working-class history continues. This month, we speak to Jeremy Zallen, whose book American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 was published this week by the University of North Carolina Press. Zallen, an assistant professor of history at the Lafayette College, answered questions from Jacob Remes.

Although I’m familiar with criticisms of light pollution and with warnings that looking at bright lights before bed impedes good sleep, I’m otherwise used to thinking of artificial light as pretty unambiguously good. But you argue otherwise. What’s to dislike about being able artificially brighten the night?

Well, I was reading the other day about a new study trying to determine the extent to which entire ecologies are being disrupted by light pollution, a problem that going carbon-free won’t solve, but what I really want people to think about are the human, animal, and ecological struggles dragged behind every lightbulb. Only research and reporting can reveal those stories. Staring at a light won’t help you see them. And the histories of some of those technologies are incredibly and surprisingly violent. I’d also say that while easy, accessible, electric light has mostly been a positive good for consumers since grids made light cheap and available, the first century of the industrialization of light, from the rise of the industrial whale fishery in the 1750s through to the destruction of chattel slavery in the U.S. Civil War, the history of light was one increasingly organized around slavery, outwork, child labor, and more (rather than less) dangerous and toxic work. This was true for both “producers” and “consumers”; most of the people burning these industrial illuminants were themselves caught up in industries that expected them to work later and later for less and less. Some upper- and middle-class Americans experienced the increasingly availability of cheap illumination as a story of leisure and play and liberation from the rhythms of sun and moon, but for a larger number of Americans, especially working-class women in cities, more light usually just meant their employers, fathers, and husbands expected them to stay up later working instead of sleeping. I think most of these working people would much rather have slept if they felt they could afford it.

American Lucifers is about both the production and consumption of artificial light. Do you have a favorite story from the production side?

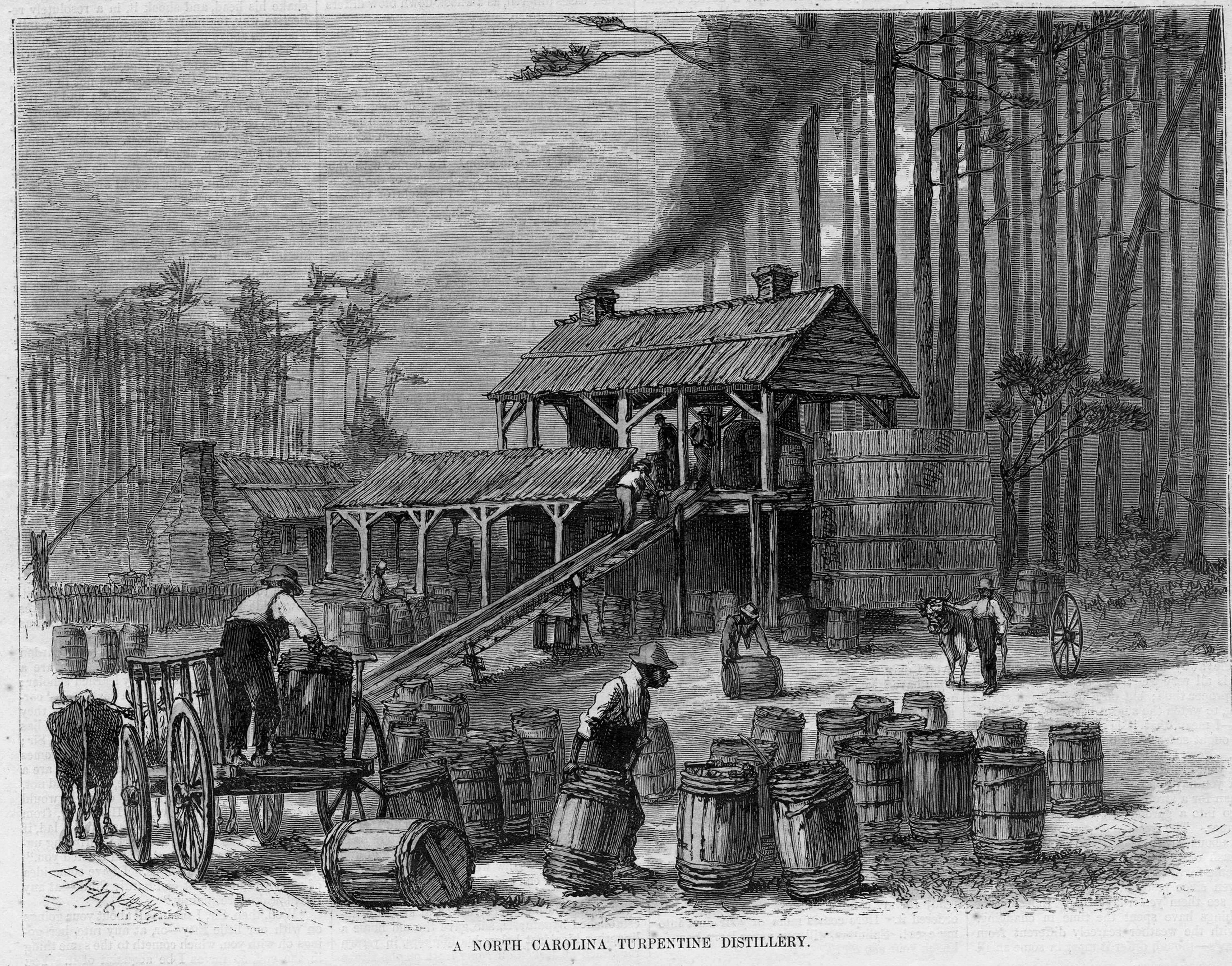

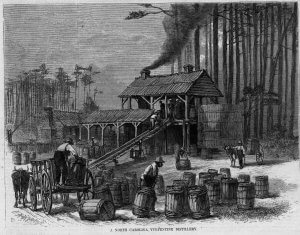

I’m not sure I’d say I have a favorite story, but the one I found the most surprising was the story of producing camphene. I’d never heard of camphene before I started this project. It was a mixture of turpentine and highly distilled alcohol, and it was the most popular illuminant in the US from about 1840-1860. The alcohol came mostly from corn-whiskey, but the turpentine came almost entirely from the forced labor of thousands of enslaved men tapping pines in the woods of North Carolina. I had no idea of the existence, let alone the scale of the turpentine industry (the third largest export from the South after cotton and tobacco). And it was slavery like I’d never read about before. Unlike the field-based plantation regimes of cotton, rice, or tobacco, or even the clearly industrial slavery of coal mining or factories, turpentine camps were places where both the arts of domination and the arts of resistance developed through centuries of struggle in plantation slavery broke down and had to be reinvented by both enslavers and enslaved. For the enslaved, finding food and shelter was harder, but temporarily escaping to hideouts in swamps was far easier. For enslavers, surveillance was far more difficult, but distance and isolation made workforces more dependent on the provisions guarded at the center of the camps. The history of producing camphene showed how both flexible and fragile systems of slavery could be.

How did artificial light change work for others?

In her 1863 report on The Employments of Women, the American reformer Virginia Penny noted that so common and so severe was the work of sewing that she could spot a seamstress simply by her posture: “‘by the neck suddenly bending forward, and the arms being, even in walking, considerably bent forward, or folded more or less upward from the elbows.’” It was a posture, a reordering of bones and muscles, shaped by years of sewing around the lamps and candles at the center of American Lucifers. Before the eighteenth and nineteenth-century revolutions in light made at least some illumination available to even the poorest Americans, seamstresses like the ones Penny noted would have had to stop working when the sun set and hearth fire went out. New kinds of artificial light meant they could (and were expected to) work longer. Other ways artificial lights changed worked could be seen in factories brightly lit by gaslights where working hours could be more readily tied to clock time rather than solar/lunar/seasonal/task time, an important part of the story of the formation of modern time discipline. The ubiquity of matches put instant fire (and potential arson) into the hands of pretty much every worker, even enslaved and child workers, which also shifted the relation between capital and labor. These are just a few examples of how artificial light changed work for others.

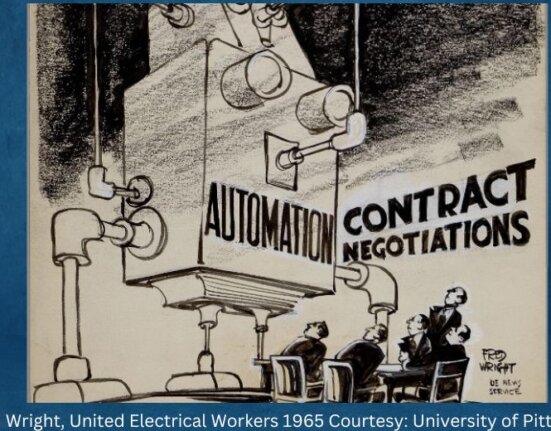

American Lucifers is largely about who bears the burdens of new technologies. Does it have anything to say about today’s new technologies–either the workers who produce them or the work enabled by them?

I hope readers of American Lucifers start to look differently at how a whole range of consumer products are actually produced and consumed, but I especially hope they reconsider the geographies and natures of technologies, like lights, that produce the very spaces we live and work in, like heating/cooling/ventilation systems, waterworks, energy grids, or the internet. Looking more closely at the entire material histories and geographies of such technologies should hopefully allow us to see more clearly the transnational linkages plundering some to aid others and enormously enrich a few. Seeking carbon-neutrality alone won’t be enough to either see or confront the full social and ecological injustices of our world today.

Now that you’re done with your book, what are you looking forward to reading?

I’ve been meaning to finish and read more carefully both Sunaura Taylor’s Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation and Timothy Pachirat’s Every Twelve Seconds: Industrialized Slaughter and the Politics of Sight to better understand how “human” and “animal” have been entangled in histories of labor and liberation in the capitalist world.