Elections in Brazil are underway. Far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro faces leftist Fernando Haddad of the Workers’ Party in the final round of the presidential election. Brian Kelly interviewed historian Sean Purdy for explanations and reflections on the right and left, austerity, and labor issues in Brazil.

BK: The rise of the far right in a country that was, even in recent memory, home to a powerful workers’ movement, has taken much of the international left by surprise, and seems a kind of ominous confirmation that the brand of right-wing populism that Trump embodies can grow beyond the US and Europe. Can you explain what’s behind this shift, and reflect on the decline of the PT [Workers’ Party]?

SP: The immediate roots of the present political crisis lie in the economic recession that reached Brazil in 2012, the subsequent explosion of struggles by unions and social movements from 2012- to 2014 and the opening for a rightward shift as a result of the failure of the reformist project of the PT to deal with economic crisis and popular struggle from below.

During the economic boom in Brazil from 2002 to 2012, the PT government was able to advance modest social reforms while maintaining an orthodox financial policy that benefitted financial and agro-industrial capital. Yet it also struck deals with the worst elements of the centre and right-wing in Brazilian politics and certainly engaged in questionable ethical practices with companies that donated money to its election campaigns.

With the onset of recession in 2012, the government began to introduce modest austerity measures. In addition to the stagnating economy, these changes provoked record strike levels from 2012-2014. The failure of the PT to deal with the appalling lack of urban mobility and paucity of decent public services provoked a massive rebellion by students and young workers in June 2013.

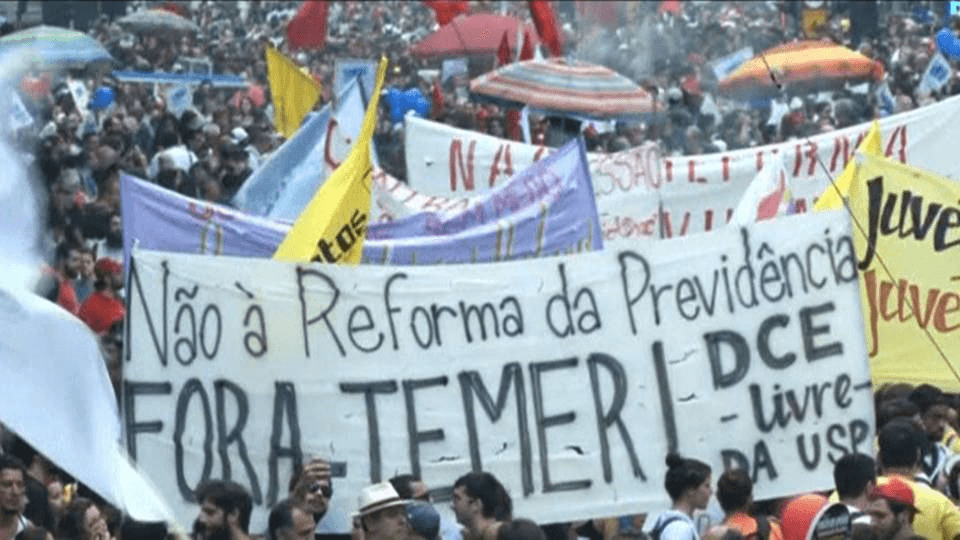

In the 2014 elections, the PT President Dilma Rouseff appealed to the party’s base through a series of promises to expand job creation and public services and narrowly won the presidency. Rather than fulfill her promises, however, Rouseff began an extreme austerity program, cutting R$30 billion from social programs and restricting pension and union rights.

The PT alienated its own base, thoroughly discredited any left-wing program and the inability of the radical left to fill the vacuum of power resulted in a rightward shift of politics, culminated in the parliamentary coup of 2016 which deposed Rouseff.

From 2016 until the present, the centre and right under the coupster president Michel Temer have consistently shifted the terrain of politics in the country, advancing outright austerity politics, cuts to social programs and attacks on the social rights of LGBT, blacks and women. Racist and anti-poor law and order politics and a disastrous incarceration policy, which has seen Brazil’s prison population rise to the third highest in the world – something which the PT did not nothing to change or even fed – have advanced and have proven to be a strong point in Bolsonaro’s campaign.

More concerned with its own political power, the PT only reluctantly engaged in a fightback in these years, opening up space for the most extreme candidacy of the right, Jair Bolsonaro, who preaches against the corruption of the PT years, but represents the most corrupt and retrograde political agenda of the far right.

BK: In Brazil and internationally the far right will be emboldened by the primary results. Bolsonaro has made it clear that he is not for tacking to the centre for the national elections, and the stock market surge that followed the primary results suggests that capital will welcome a president who looks back nostalgically at the years of military dictatorship. What is the constituency for Bolsonaro’s politics, and to what extent has he succeeded in making inroads among those who would have voted PT in the past?

SP: It will come as little surprise that Eduardo Bolsonaro, the son of the presidential candidate and a federal deputy, met with Steve Bannon in August of this year in New York. The active base and leadership of the Bolsonaro campaign is middle class with key elements from the armed forces, police forces and, more recently with his growing popularity, a section of the capitalist class including bankers, agro-business and industrialists. Almost all the centre and right-wing parties have jumped on his bandwagon as have the right-wing social movements that emerged during the impeachment process in 2015-2016. Polls show that the bulk of his support comes from those with higher incomes and education and from the industrial and more populated states of the southeast while the opposition PT candidate, Fernando Haddad, is supported by the poorest voters and by large majorities in the northeastern states. Not surprisingly, women and blacks have rejected Bolsonaro in larger numbers than men and whites.

Yet he has also gained the support of millions of Brazilian workers around the country. The right has been able to capitalize on the very real, if frequently exaggerated and distorted, history of corruption by PT governments, the grave economic crisis, a highly orchestrated and illegal campaign of fake news about the economic policies and social positions of the left and the implicit backing of the corporate media. Desperate after 4 years of severe recession and buying into the supposed anti-politics and corruption-free campaign of Bolsonaro, many believe that he offers a fresh alternative. The PT erred in launching Haddad as the candidate late in the process and despite tacking to the left during the campaign has been unable to turn a tide which began months earlier.

It is important to stress that Bolsonaro’s claim to represent an alternative is a breath-taking lie. He has a long, documented history of shady corrupt practices as have many of his institutional supporters. He has recently embraced neoliberalism despite a long record of supporting state-led economic development and special privileges for the military and police castes. His advancement of racist, sexist and homophobic agendas and explicit threats to mobilize against democratic governance if he loses are regurgitated reactionary positions long supported by the far right and supporters of the military regime from 1964-1985. The current ruling class and its institutions have basically caved in to his anti-democratic agenda despite illegal campaign donations and practices and threats by Bolsonaro and his supporters that they will not hesitate to overthrow democratic institutions if necessary. In a speech on October 21, Bolsonaro promised that there would be a “cleaning up like there has never been in the country… I’m going to wipe the red criminals off the map…These red criminals will be banned from our country. They will either leave or go to jail.” This consistent incitement to violence during the campaign has resulted in over 80 documented cases of physical aggression against supporters of Haddad and the left, including at least two deaths.

BK: One element in the shift to the right in Brazil that feels familiar is the role of right-wing evangelicals in bolstering Bolsanoro’s candidacy: they’ve been won on the basis mainly of ‘hot-button’ issues like abortion rights and a reaction against LGBT freedom. Bolsonaro seems to relish his reputation as an unapologetic misogynist. Yet it wasn’t that long ago that it was the left that could lay claim to the loyalty of many Christians. What has changed, and to what extent has this been part of a deliberate strategy for the right?

SP: The majority of evangelical Christians overwhelmingly supported the PT governments under Lula and Dilma from 2003-2014 since the economy was reasonably prosperous and the PT only reluctantly advanced social rights. Advances in LGBT rights and the right to choice in abortion (which has still not been won) were never openly pushed by the PT, but have advanced through struggle from below. Yet the evangelical churches are first and foremost barely veiled businesses interested in increasing their vast wealth. When the tide turned for the PT with impeachment in 2016, the churches put their lot in with the new forces of the right, which promised them more opportunities to accumulate wealth. Despite laws banning election campaigning in churches, pastors have openly campaigned for Bolsonaro in sermons and other events, spreading the fake news that the right has been cultivating for several years. The second largest TV network is controlled by the largest evangelical church in the country and has consistently campaigned for Bolsonaro, to the extent that journalists have been coerced to attack only the PT and give favourable coverage to Bolsonaro. With the late start to the campaign, Haddad has not been able to counter even the most blatant lies of the church leaders who support Bolsonaro.

BK: The Brazilian establishment has for a long time promoted the notion that Brazil was a ‘racial democracy’ – a racially and ethnically mixed society in which race didn’t matter. This has been the official line even when all the statistics show a very clear correlation between race and social and economic inequality. Does this make it more difficult for Bolsonaro and the right to indulge in the flagrant racism that we’ve seen from the Trump White House, or from the right in Europe?

SP: It is not an exaggeration to say that there has been a near-genocidal racist police policy against Brazil’s majority black population. They are disproportionately victims of police forces that killed over 5,000 people in 2017. Bolsonaro and supporters have been caught out in vicious racist statements numerous times in the past, but certainly the myth of racial democracy and the peculiar form of racial relations in Brazil has meant that this is less of a hot-button question than in the US or Europe. Bolsonaro’s party elected numerous black candidates and enjoys expressive, if minority, support among Afro-Brazilians concerned with the economy and the crime wave. This is an extremely complicated question, but the level of racial identification and mobilization around anti-racist politics is much less than in the US. So Bolsonaro, despite his blatant racism, his law and order politics which will affect blacks above all and his anti-affirmative action policies (despite their massive success in universities and public sector employment) has been largely able to side-step this question.

BK: You’ve painted a picture that suggests the once-powerful Brazilian left is down but not out. What are the prospects that the fragmented left can pull together to defeat the Bolsonaro candidacy? What is the feeling among the PT grassroots who, as you say, have been let down by the party bureaucracy but who perhaps have some fight in them still?

SP: It’s extremely unlikely that Haddad will be able to turn the tide, but the left continues to resist. The PT base and the far left have mobilized frenetically in the last weeks and believe that a 52%-48% win by Bolsonaro would be better than 60%-40%, for example. Sections of the centrist parties, the corporate media and honest democrats have also come out in support of Haddad in face of the Bolsonaro threat. The massive, women-led #elenão demonstrations in late September proved to be a massive boost of confidence.

But it would also be amiss to ignore the widespread demoralization and fear among the left, the PT grassroots and the oppressed. The first task after a Bolsonaro win will be to ensure the physical integrity of the left and the oppressed. In the October 21 speech, Bolsonaro threatened to “wipe off the map” the left – particularly the landless and homeless workers’ movements – and his incitement to violence will certainly inflame his most ardent supporters and the already murderous police. He has suggested that army troops could be used to regularly patrol urban areas, building on the disastrous military intervention in Rio de Janeiro, which since its implementation in February 2018 has only increased violence in the city. There have already been preliminary mobilizations of “Self-Defence Brigades” in LGBT areas of several big cities.

The principal question in relation to a Bolsonaro government will be his inability to solve the economic crisis, which could provide space for the mobilization of the organized working class. But this will require sustained arguments from union militants against the ossified and timid union bureaucracy. There will be a tension between the neoliberal policies he has recently adopted and support among many of his voters for decent social programs and labour rights. His supposed anti-corruption policies will come under scrutiny, as he staffs his government with a band of long-standing corrupt criminals and army generals. He may even face corruption charges for illegal election practices such as funding a massive fake news campaign, though the justice system is unlikely to actually implement the law.

International solidarity will be essential for us in the coming years. A Bolsonaro regime needs to be denounced by the international workers’ movement, the left, all democrats and supporters of human rights. Our struggle is your struggle.