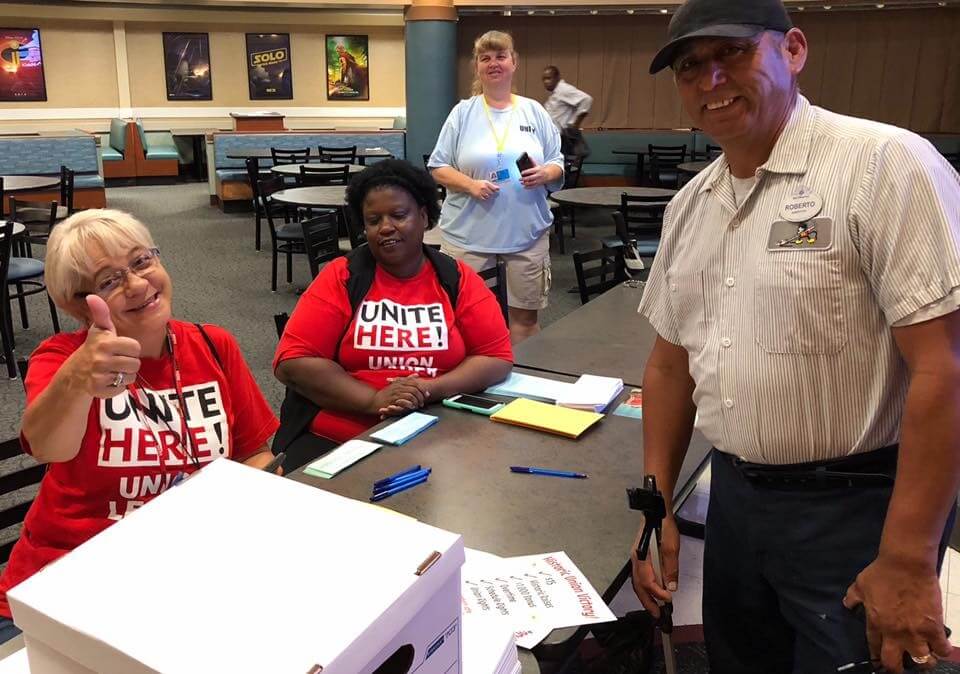

Over the better part of the last year (July 2017-August 2018), Disney cast members in both Anaheim and Orlando have been negotiating with Disney and have signed what has been called a historic contract. A true David and Goliath story, they and their unions have been going toe to toe with one of the most sophisticated, cut-throat, and best funded legal teams in the world, and they seem to have won at least a partial victory. By 2021, many more, but certainly not all, of Disney’s workers on both coasts will be earning $15/hour. While the wage increase applies to all of the over 34,000 union members who make up the Service Trades Council Union (STCU) in Orlando, it will apply to less than half of Disneyland’s workers leaving the majority in Anaheim, where the cost of living is highest, making less than $15/hour. Hotel, janitorial, and restaurant staff, bakers and candy makers, and drivers can all now look forward to a raise but food and beverage workers (who make the least of all the workers on both coasts) in Anaheim are left out of the latest deals.

While there are distinct stories unfolding on each coast, Disney, claiming to be offering the “highest wage increase in history,” has in reality been backed into a corner and likely sees this as a good PR move ahead of the $15/hr it will have to pay anyway once California’s minimum wage law goes into effect in 2022 (gradual increases up from $10/hour are going into effect each year until then). The largest increase in history may even spell defeat in California, given the fact that Disney’s $15 minimum, applying only to 8600 of its workers, is significantly less than the $23/hour living wage necessary to make ends meet in Anaheim. Some union members are convinced that Disney left some unions’ members out of the deal in order to undercut Anaheim’s current living wage initiative set for a vote in November. Ultimately the Disneyland deal may end up doing more harm than good if the ballot initiative is defeated.

Nevertheless, the eventual $15 minimum at Disney may be historic for what it represents for the service, retail, and hospitality industries and it certainly offers more than Disney would have preferred. Over the course of the year, the situation looked bleak. Last summer (2017), Disney’s legal team–despite story after story of cast members living in their cars, in hotels, not being able to afford tolls, making the same $9.77/hour after 15 years on the job because they had “topped out” at the maximum hourly wage, doubling and tripling up in one-bedroom apartments–refused to budge. Disney argued that any increase would cut too heavily into its $180 billion profit margin. The unions countered that the increase to $15/hour for the union’s members amounted to just 3 cents on every dollar of profit Disney makes. Over the winter, Disney tried one of the oldest tricks in the book: it threatened to withhold the $1000 bonuses it was distributing, inspired by the Trump tax cuts, from union members. Disney’s unions filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the NLRB sided with Disney. Many of us thought it was over at that point but unions on both coasts managed to keep cast members relatively united behind the $15 minimum and they managed to ensure that the bonuses were paid.

What has resulted is, indeed, historic. Just how historic we won’t know for some time. But it may it has the potential to be the equivalent of the UAW’s 1936 sit-down strike, accomplishing for the service industry what the 1936 strike ultimately ushered in for manufacturing. The sit-down forced the big three auto manufacturers to recognize the UAW as its bargaining agent. Once the UAW was in place and in the context of the booming postwar economy, the UAW effectively turned what were low paying, assembly line jobs, the purview of recent immigrants (who have consistently entered the US work force at the lower end) into good paying jobs that would eventually constitute part of the foundation of the growing postwar middle class. Immigrant factory workers no more, a job at an auto factory was highly coveted, came with overtime, paid vacations, pensions, and health insurance. Subsidiary industries followed suit and, together, good paying manufacturing jobs sustained the postwar middle class until it all started to unravel in the 1970s.

As GM, Ford, and Chrysler did for the auto industry, Disney (along with Walmart and McDonalds) sets the standard for the service, retail, and hospitality industries. Employers throughout will have to follow suit and begin a process of raising wages should they hope to attract hard-working employees. If Disney can do it, so can and should the others including Universal, the big hotel and restaurant chains, the fast food industry, creating a ripple effect this time in the direction of higher wages across the board. The pressure on the whole of the industries will increase as Disney’s new norm takes hold. Disney’s unions just might be able to build upon this success to push toward a higher, living wage, minimum over the next five years even if the Anaheim initiative doesn’t pass. This new floor should also force the rest of the scale to adjust upward, with other employers following suit and, at least theoretically, Anaheim and Orlando’s local economies should improve dramatically with everyone, including Disney corporate, benefitting.

As important as raising the wage scale is the fact that, unlike the runaway U.S. auto manufacturers, the service and hospitality industries are here to stay. The only way Disney will be able to avoid paying the $15/hour across the board minimum is by hiring immigrants on H-1B visas or some version of them (perhaps that’s in the works, a behind-the-scenes resurrection of its 2015 attempt to do so) and initiating a kind of modern “bracero” program in which the U.S. government sponsors temporary workers below minimum wage rates and/or by “adjusting” people’s schedules so they’re working fewer hours (Orlando’s STCU fought this in June). Versions of these may happen, stranger things certainly have, but, for now the $15 victory is more than symbolic and has the potential to change the paradigm around service, retail, and hospitality work.

Disney, the corporation, has made out like a bandit now for over a half century because of the ways in which assumptions about “service” work played in the wage structure the corporation set up years ago. Like other service and hospitality jobs, including fast food and retail, the model developed in an era during which the jobs were largely temporary, the purview of moms with older kids, teenagers who needed a summer job, and newly arriving immigrants who used the temporary jobs as stepping stones to other employment. Disney continues to make billions (not an exaggeration) and has for decades now using these assumptions to keep wages low despite the fact that times have long changed. Over the last decade labor unions have worked to upend those assumptions and, here, with the new Disney contract, perhaps the most important victory has been won. Because of the changes in the U.S.’ economy over the last forty years, these jobs have long ceased to be temporary, or the purview of moms working for pin money or teens in need of some experience, and they were never, contrary to those all-powerful assumptions, unskilled. Disney’s unions have very effectively confronted that mentality. Union members have spent countless hours confronting Disney executives with their all-too-real stories of economic despair and hardship. They threatened a hunger strike. Bernie Sanders spoke on their behalf. Few(er) of us think Disney’s cast members are working “for fun” or for “pin money” as a result and those who do are simply engaging in willful ignorance. Even the “better off” college students Disney employs over the summer or by the semester, are finding it less and less possible to start their careers debt free. While they are not included in $15 contracts, Disney is now in the process of instituting a college tuition assistance program perhaps as a way to avoid extending the $15 minimum to them.

In any case, it’s clear here as it is historically that wage rates are more often than we acknowledge based NOT on what the company can afford to pay but what they can get away with paying and how they can justify it. This was certainly not Walt’s attitude but he contributed to it. While Walt was never in the business for the money, especially in the early years, he had a healthy ego and enjoyed being in charge. With only a six-person team, Walt changed the name of the studio from the Disney Brothers’ Studio to the “Walt Disney Studios.” As a young upstart animator, Walt, also the consummate salesman, inflated himself to the status of a lie to convince movie houses to buy Disney Studio shorts. Walt had no problem being the boss-owner and, within the U.S.’ capitalist private-ownership system, that role was widely encouraged and a marker of success, even, in Walt’s case, in the depths of the Depression. Since it was Walt’s idea to create an animation studio, the studio became “his,” he was in the position to hire, fire, and make all wage-related (and other) decisions and he was in charge of justifying who was paid what.

Disney’s service model grew in the context of the 1953-1955 creation of Disneyland. Walt Disney charged Van Arsdale France with the not-so-small task of bringing the magic of Disney’s films to real life in an amusement park setting. Most of us are familiar with the brilliant aspects of the model they came up with. Not only was the park itself the antithesis of Coney Island, less carnival-esque and much more wholesome and family friendly, the workers themselves were imbued with a great deal of responsibility. They were never “workers” putting in the required hours on the job and collecting a pay check but “cast members” who had the bigger responsibility of delivering that magic to their “guests’ (parkgoers). Brilliant for many reasons not the least of which was that if you feel you are delivering something so important while driving people to their destination, cleaning their rooms, or pulling a lever on a ride, the monotony of the task is imbued with a greater importance one that makes you feel perhaps more important than you are but one, too, that enabled you to forgo the fact that you were working twelve hours a day in a hot suit for minimum wage. It is the cult surrounding working at Disney as a cast member delivering the magic that has done more to obscure the exploitive conditions that developed since 1955, conditions that at are at least partially responsible for the profits the company has enjoyed.

Even before Disneyland opened, Walt carried his assumptions about who deserved what into the pay structure in a kind of gradual process that followed his and the studio’s fortunes. Walt always positioned himself as the guy in charge but, until the studio hit the big time, he was more just one of the guys and he was young, their age. Whatever minimal profit the fledgling studio made in the 1920s and early 1930s was distributed amongst the handful of people, not evenly, mind you (the one inker and painter were paid less than the animators). Walt really had no choice. They all lived from short to short. Walt would pay the bills whenever some bits of money came in often not paying himself much of anything and the others the rest with the hope that they’d stay to work on the next project. By the mid-1930s as the team grew and started work on Snow White, pay was still based on this haphazard kind of arrangement and Walt was still just a bit more than one of the guys. They (now upwards of 100 people) worked 16-18 hour days leading up to Snow White’s release all knowing that if it was a hit, they’d all reap the rewards. They were still a creative team, not yet “employees,” with Walt a kind of captain. What would become the academy award winning full-length animated film Snow White would also be the last film from which pay was distributed based on the profit the project generated. While Snow White brought Walt Disney Studios enormous success, it also ushered in a larger work force, a new pay structure, and a “big boss.”

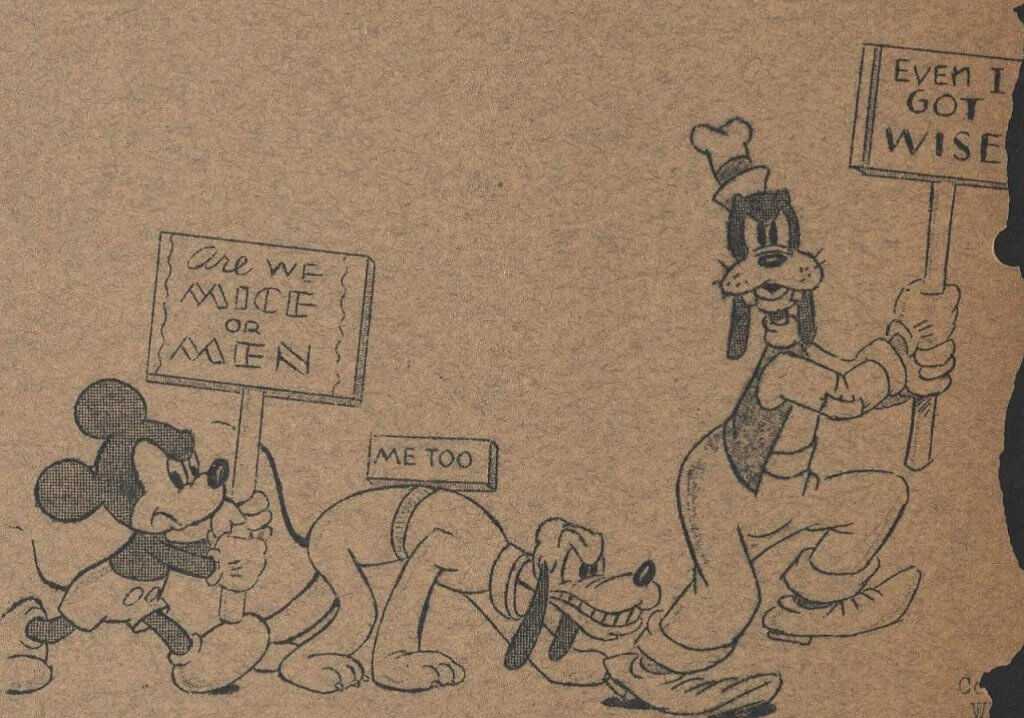

More people, animators, production assistants, inkers, secretarial and custodial staff, and a new studio all in preparation for the next big success. There was a moment when Walt became a boss and not an animator, when he and his brother became “owners” of the “company” and not young men trying to scrape out a living alongside similarly-situated young men. Once that point was reached, there was little chance for the Disney cast members of the future to earn a decent living. Much of this mindset shift had occurred between 1936 and 1941, between the success of Snow White and the famous June 1941 strike. Walt’s move to “boss” was not missed on his, now, employees and was one of the chief complaints leading to the strike. Not only had Walt replaced a share-of-the-profits pay formula with a wage scale, he played favorites by handing out bonuses willy-nilly. As the owner of the studio and with all the attention and expectation directed at him, Walt drew the ire of his animator-artist-workers by positioning himself as the gatekeeper for all “quality” animation and storyline. A great admirer of Henry Ford, Walt more than willingly assumed the role of a paternal figure to an up and coming union-oriented group of now younger men-animators-who came of age under the pro-labor Wagner Act and bristled under his direction.

The 1941 strike was the dividing line, a key turning point for both Walt and the Studio. Occurring during the summer of that year, it ushered in one of the least successful eras in Disney’s history, one during which the studio relied first on wartime propaganda films and then bland, formulaic storylines, at least as they were received at the time, to pay the bills. Had he not made life miserable for the creative team of animators who spearheaded the strike, and who all eventually left, the spark that marked Disney’s films would likely have remained. Instead an embittered Walt retreated. For the first time in his life, his biographers tell us, he did not go into the office every morning. The day-to-day operations were left in the hands of a team of managers, all a part of a new cohort of professionals who were seeking MBA degrees at alarmingly high rates. The beautiful new campus Walt and his brother built in Burbank, a work setting the envy of all who saw it, proved a poor substitute for the kind of camaraderie that marked the early years at the famed but too small Hyperion Ave studio. In Burbank, Disney animators had their own offices, took breaks whenever they needed them, and worked together on classics like Cinderella but Walt considered them employees, they were hired and fired at will, they learned to play his game, and ingratiate themselves just enough to extract a bonus if they could. They played the kid to the father-like boss.

Labor historians are not easily fooled by arguments about supply and demand although the management teams who took over the daily operations at the studio applied those arguments to the Disney work force, one now separated from “management.” Disney was not yet a driving force in U.S.’ employment policy but merely followed the trend as the corporate model took hold in the postwar U.S. Across the country, “organization men,” mid-level managers with college degrees, earned a decent living, were anti-union company loyalists, their identities and salaries elevated by the fact that they weren’t line or grunt workers. Meanwhile, Disney’s workers, as opposed to its managers, were unionized. Everyone from the very highly paid animators to the inkers, painters, and set construction crew were unionized. The International Association of Theatre and Stage Employees (IATSE) was the most prestigious of the unions that negotiated with Disney. It represented a kind of middle-of-the-road union in the postwar period. It was less radical, less demanding than the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild (SCG) had been but not as much of a push over as the Federation of Screen Cartoonists, the pro-company union organized with Disney’s blessing in 1937 and a counter to the SCG during the 1941 strike. The IATSE emerged from the strike as the most reasonable (if not the most effective) of the three and Disney’s remaining animators voted to have it represent them in 1952. By that time, Disney was negotiating separate contracts with plumbers, carpenters, and masons’ unions, among many others. It was a typical postwar company in that regard and could claim to be pro-union in the 1950s, labor-management accord, post Taft-Hartley sense of the term.

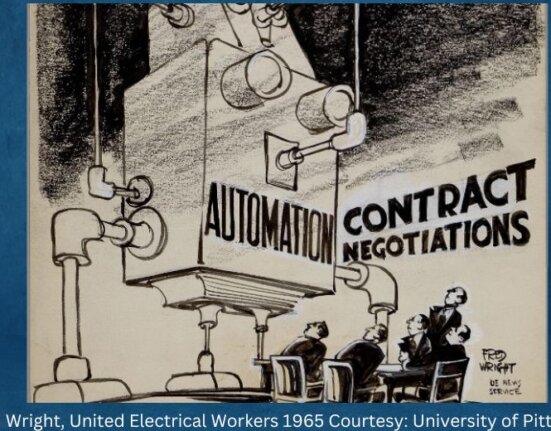

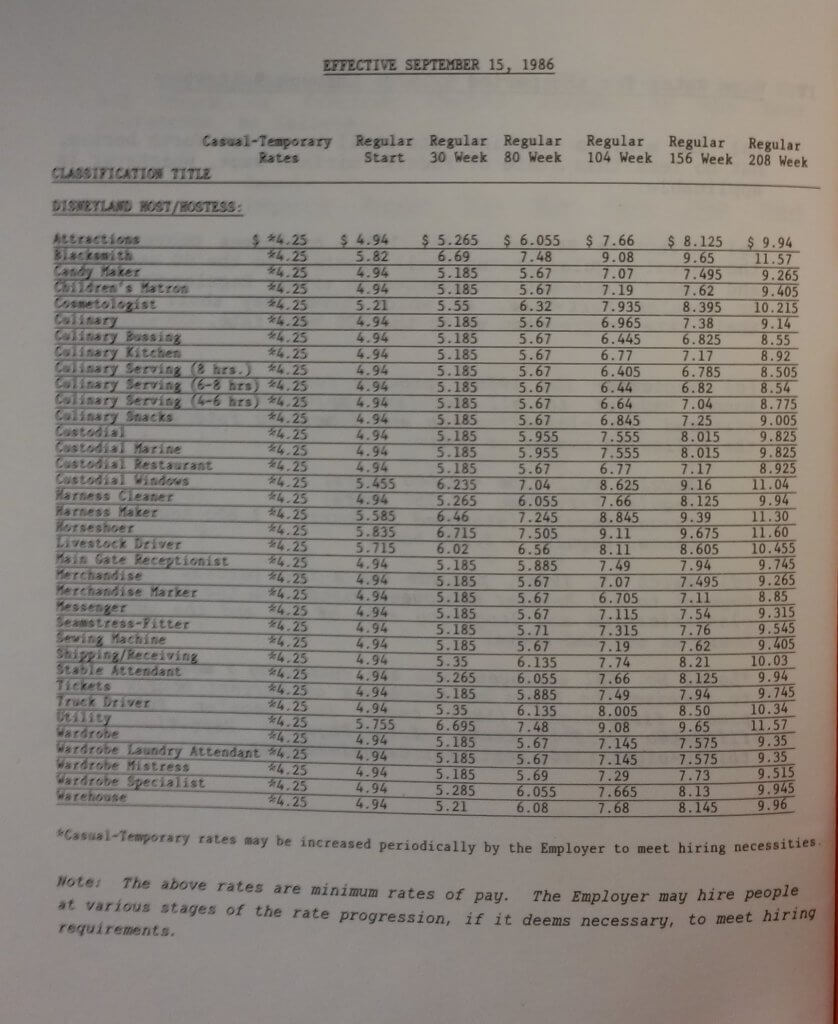

Once the plans for Disneyland were laid, things changed. Disney no longer followed trends but created them. A massive undertaking, Disney began to negotiate now with hundreds of labor unions as it contracted for laborers. It also literally created a new work force all engaged in a completely innovative customer service model, one that has gone on to set the standard in the service, retail, and hospitality industries. That standard developed around a largely “female” retail, “temporary” teenager, and entry-level wage rate in a time period during which manufacturing (think auto industry) jobs provided the theoretical “living” and even “family” American wage. Even though Disney’s first cast members knew they were working hard, long, hours and the pay was low most accepted it as part of the privilege of working for Disney, others had their husband’s or father’s wages to supplement theirs, and still others (a minority) tried to do something. In 1965, for example, pageant helpers filed a grievance through their union, the American Guild of Variety Artists of America, and argued that they should make as much as the costumed cast members. Disney responded that the pageant helpers didn’t deserve a raise, they were “just part of the atmosphere,” and not essential to the production! Assumptions are both arbitrary and everything. By 1965, Disney’s wage scales covered over 1000 different categories of worker at all skill levels whose wages were calculated to the penny, with unions as obscure as the “Inland Boatsmen” to the Teamsters negotiating contract after contract. The company’s labor relations department supplemented its own bloated self by keeping the wages of thousands of Disney’s workers at the barest of minimums and separated into hundreds of categories to avoid any attempt at collective action.

Most, not all, but most of what makes up a wage scale has to do with the assumptions, societal and personal, associated with a particular position, with the person who occupies it, all overlaid with, usually and certainly in this case, “management’s prerogative” to keep wages both as low and as hierarchical as possible. But when did this mindset set in at the Disney Studio and how did it end up creating a wage scale that has since rendered some of its workers homeless? While assumptions about pay were always a part of the decision-making process, Disney has succeeded in milking those assumptions along for decades even when they no longer applied. If this most recent valiant effort by Disney’s unions and those behind the living wage initiative in Anaheim has done anything, it’s to clarify that service industry jobs have not been temporary for decades but are permanent jobs. The service, retail, and hospitality industry employers, including Disney, need to pay a wage that allows their permanent employees to live comfortably at whatever rate is necessary. Multi-billion dollar corporations, Disney, Walmart, McDonald’s, can afford it.

Select Sources

Brady, Thomas. “Whimsy On Strike,” New York Times (June 29, 1941), p. D3.

Gabler, Neal. Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. New York: Vintage, 2007.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Contract Collection. The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives, Cornell University. Ithaca, New York.

Collective Bargaining Agreements, U.S. Department of Labor. The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives, Cornell University. Ithaca, New York.

Lipp, Doug. Disney U: How Disney Develops the World’s Most Engaged, Loyal, and Customer-Centric Employees. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013.

Papers of the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild. Special Collections, University of California-Northridge. Northridge, California.

Sito, Tom. Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson. Lexinton: University of Kentucky Press, 2006.

Watts, Steven. The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001.

https://money.cnn.com/2018/08/25/news/companies/walt-disney-world-minimum-wage/index.html

https://www.ocregister.com/2018/07/26/disney-to-set-entry-wage-at-

http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-anaheim-living-wage-20180619-story.html

15/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/27/us/disneyland-employees-wages.html

Lisa Philips is the author of A Renegade Union: Interracial Organizing and Labor Radicalism. She is working on history of labor relations at Disney and teaches at Indiana State University.