The Chicago Teachers Union’s (CTU) recent decision to boycott Illinois Standards Achievement Tests, its efforts to fight privatization of education and school closures, and its attempt to break free from business-as-usual politics harkens back to a rich and largely hidden history. As teachers struggle to regain power in the midst of continuing assault, this history might provide some frameworks for considering new possibilities for coalition-building and a campaign for the public good–and not only in Chicago. Georg Leidenberger’s Chicago’s Progressive Alliance (2006) provides an in-depth look at the role of unionizing teachers who interwove a struggle for their workplace rights with reform of the schools. The book shows how the teachers articulated the argument that union power would assist democratic struggle. Their starting point was coalition building in the local community.

In the early 20th century, the Chicago Teachers Federation, led by the indomitable Margaret Haley and Catherine Goggin, fought the efforts of the Chicago Board of Education to centralize power in administrators’ hands in their schools. Teachers demanded direct election of the school board in order to empower parents as well. Connecting the struggle to unionize with a broad campaign for the public good, Haley wrote to reformer Jane Addams in 1906: “For seven years, I have led the teachers in a struggle to prevent the last institution of democracy, the public schools, from becoming prey to the dominant spirit of greed, commercialism, autocracy, and all the attendant evils. . . If you could know how deeply I feel that the perpetuation of our democratic republic depends on the success of the struggle.”

To campaign effectively for schools as a public good and to fight for teacher control of the classroom, the CTF affiliated with the Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) and played a critical role in removing the grip of the building trades’ grafters on that organization. They were a major part of the coalition that brought John Fitzpatrick, the Irish immigrant known for his willingness to open the doors of the federation to immigrants, reformers and radicals, to leadership of the federation.The other major player in the coalition was the teamsters union, whose practice of the sympathy strike (refusal to transport goods to and from workplaces on strike) was the vehicle that built a broad-based labor movement into play and helped to make Chicago the leading union city in the country.

Within a few years, teachers were part of a coalition that articulated a “public interest” agenda and sought to speak for the “business of the community as a whole.” A key campaign was for municipal ownership and management of the transit system in Chicago, and they came close to succeeding on this issue. Their target was the corrupt privatized streetcar system that undermined the notion of public transportation as a public good. Teachers sent home literature with their students about the issues to working class neighborhoods long abused by inadequate streetcar service, and that sealed the perception that teachers were a positive force for change not only for themselves, but for the entire city.

In fact, it was their effectiveness that brought a wave of employer organizing to stymie these ambitious plans. Leidenberger argues that it was success, not lack of favor, in working class and reform communities that should be remembered. For a time, middle class reformers looked to teachers and teamsters to guide their vision of the public good. Middle class allies were not wedded as yet to the notion that workers were the pawns of graft and boss control, but instead viewed them as the base for a vibrant democratic agenda; teachers were intermediaries between groups and were central to that vision. It was this threat that led employers on a campaign to eliminate the community-oriented sympathy strike, and to launch a sophisticated PR campaign similar to that which had squelched the 8 hour movement 15 years earlier. This public campaign sought to label labor unions as antithetical to the public interest (sound familiar?) and to weaken the alliances between labor and middle class reformers. The sympathy strike was countered with a wave of repression and backhanded bargains but was also defeated due to racial divisions. Teachers unions faced fatal legal challenges including the infamous Loeb rule, which prohibited teachers from affiliating with organized labor, a “yellow-dog” contract provision upheld by the Illinois Supreme Court in 1915.

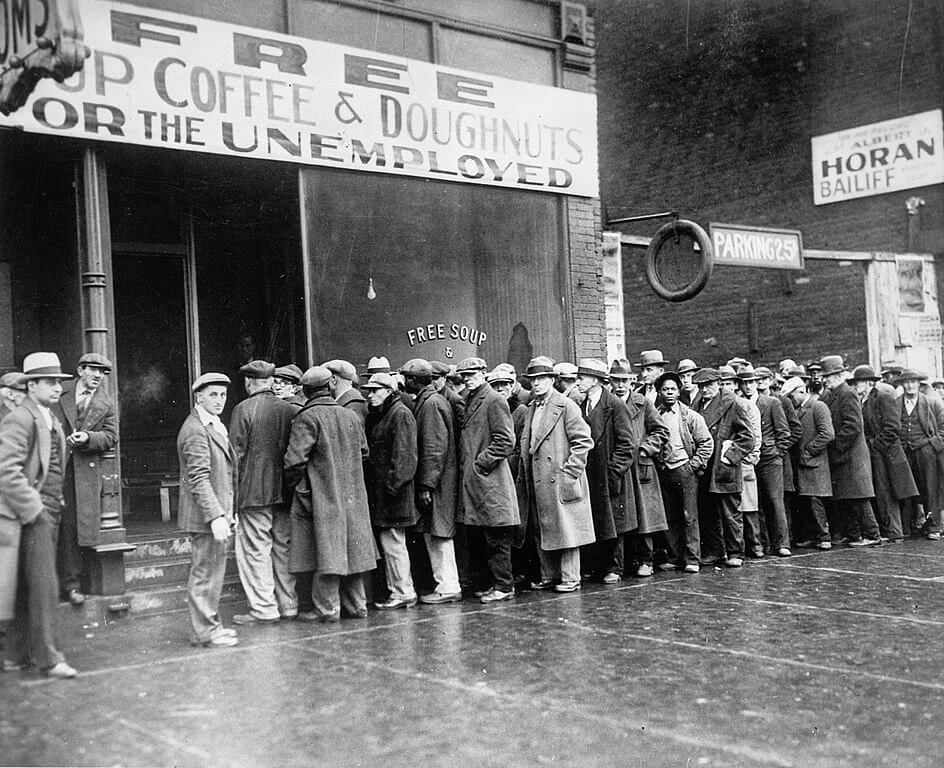

When teacher unionism revived in Chicago in a later period it did so within the confines of the primary goal of collective bargaining; that encouraged a kind of tunnel vision toward the contract. For many teachers, the efforts to gain the representation rights that private sector workers had–to bargain collectively over pay and conditions–supplanted a broad-based campaign and coalition building. John Lyons’ recent book, Teachers and Reform: Chicago Public Education, 1929-1970 highlights the role that racial divides played in Chicago in stymieing a broad based campaign for the public good. But even where teachers were not racially divided, the focus on contract demands separated them from vibrant community coalitions.

Teachers unions often ask for public support during their contract demands; seldom have they taken the kind of proactive leadership roles that the CTF initiated in this era to help create a new public sphere. Teacher unions has been adhering to the contours of a collective bargaining regime for a long time, and that prevails over the kind of campaigns that animated the origins of teacher unionism in Chicago.

The CTU wants to break from those confines, and truly it seems that doing so is vital to a revived campaign for the place of education in the public sphere. It’s hard to imagine a return to a situation where teachers and teamsters (or other workers) have a real base of power to demand rebuilding of a democratic culture that has been so systematically starved. But reminding ourselves that at one point they did dream such possibilities connects the defense of the public sector unions to the defense of public welfare.

Building community-based coalitions seems to have been a powerful tool to combat the first Gilded Age structures of power. In the face of attacks on collective bargaining, awakening a larger sense of the role of public education in a battle against power structures seems to be a logical response to the second Gilded Age.

The need to support this kind of radical re-education and connecting the past to the future is part of the mission of LAWCHA.

This blog initiates of an attempt to think of the past–it’s problems, heritage, and lessons–to shape the future of public sector unionism, especially for teachers.

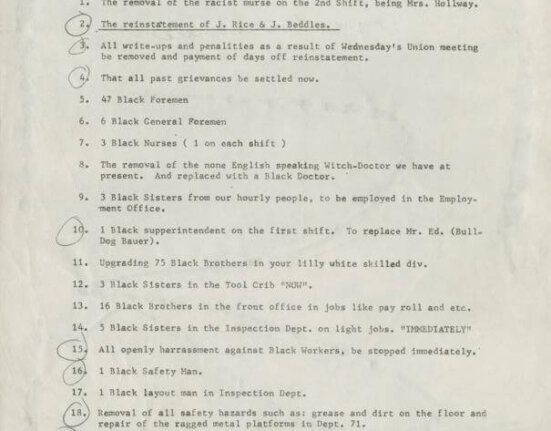

We hope you join us in this conversation. Soon we will be presenting a bibliography of materials we have developed to highlight the past in order to confront the future. We welcome your thoughts and comments. Are you interested in this issue? Do you have examples of how teachers unions ARE connecting their struggles in this way? Do you have some historical insights into these problems? What are your concerns and questions? Would you be interested in contributing a guest blog on issues related to this subject? Do you have a historical document that provides insights into the past? Let us know. E-mail me at rfeurer@niu.edu

1 Comment

Comments are closed.